Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s spoilers for Watchmen, and they’re coming this way! We’re through the actual comic book section of Watchmen #1, and on to its wonderful prose supplement, the first two chapters of Hollis Mason’s autobiography, Under The Hood.

In chapter 2, Mason starts with stories of his grandfather’s moral sense and his own experience on the New York City police force, cites with his love of pulp adventure fiction like The Shadow, and finally builds to a rather shamefaced declaration of his crimefighting career as Nite Owl I: “Okay. There it is. I’ve said it. I dressed up. As an owl. And fought crime.” From there, he explains that it was Action Comics #1, from April 1938, that began his owlish career:

There was a lot of stuff in that first issue. There were detective yarns, and stories about magicians whose names I can’t remember, but from the moment I set eyes on it, I only had eyes for the Superman story. Here was something that presented the basic morality of the pulps without all their darkness and ambiguity. The atmosphere of the horrific and faintly sinister that hung around The Shadow was nowhere to be seen in the bright primary colors of Superman’s world, and there was no hint of the repressed sex-urge which had sometimes been apparent in the pulps, to my discomfort and embarrassment. I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane, but I’d bet it was nowhere near as innocent and wholesome as Clark Kent’s relationship with her namesake Lois.

As the annotations point out, Action Comics #1 was “the first appearance of Superman and perhaps the most important single work in the development of the superhero.” So I read it. And Mason is right — there’s a lot of stuff in there, but the 13-page Superman story is clearly what’s important. So I’ll maintain a focus on that, and not worry too much about Pep Morgan, Zatara, Scoop Scanlon, Tex Thompson, Sticky-Mitt Stimson, and all the rest.

Actually, it’s probably more correct to say “Superman stories”, plural — in those 13 pages we get Superman’s origin, Superman saving a woman wrongly convicted of murder, the introduction of Clark Kent, Superman defeating a wife-beater, the introduction of Lois Lane, Clark and Lois going on a date, Lois getting kidnapped, Superman defeating the kidnappers, and Clark getting sent to the fictional South American country of San Monte but instead heading to Washington D.C. and tackling congressional corruption. In modern comics, it would probably take a year to tell all those stories.

So what did Hollis Mason see in that first issue, and how did it influence him? Page one features an extremely compressed version of Superman’s spaceflight from “a distant planet” (not yet Krypton), and his incredible powers emerging in childhood and adulthood. There’s even “a scientific explanation of Clark Kent’s amazing strength”, invoking the proportional lifting and jumping abilities of ants and grasshoppers — unknowingly foreshadowing the strength and agility of a certain bug-based character of the future. But Clark’s abilities aren’t the ones we’ve come to know today. There’s no heat or x-ray vision, no super-hearing or super-breathing or super-thinking. He can’t even fly. The story says he can “leap 1/8th of a mile; hurdle a twenty-story building,” but he wouldn’t hover or swoop in the comics until years later.

Still, what’s clear is that, like Hugo Danner before him, Clark Kent has powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. Hollis Mason, a mere mortal himself, couldn’t have hoped to compete. Even though Superman’s powerset is far from what it would become, it was well beyond anything Mason would ever achieve. In fact, when a real super-being does come along, Mason realizes immediately that he is suddenly irrelevant: “The arrival of Dr. Manhattan would make the terms ‘masked hero’ and ‘costumed adventurer’ as obsolete as the persons they described.” So Superman’s superhumanity couldn’t have been what inspired Mason to his own crimebusting career. But Superman was more than just strength, speed, and toughness.

Once the story proper kicks in, we find Superman carrying a bound and gagged woman, then leaving her on the ground so he can burst into the governor’s house, breaking down first a wooden door then a steel one. He shrugs off a bullet and tosses off a few sarcastic quips in the process of bringing a signed confession to the governor, who is the only one that can pardon an innocent woman about to be electrocuted. A couple of the panels even helpfully provide an inset clock, ticking down to midnight, showing how many minutes Evelyn Curry, the innocent woman, has left. (Hmm, now where have I seen that image before?) The guilty woman, according to the note Superman leaves behind, is “bound and delivered on the front lawn of your estate.”

So here we have Superman using those incredible powers and abilities to prevent an injustice, save an innocent, and punish the guilty. It’s a theme that will repeat twice more in the issue. First, Superman interrupts a domestic violence incident (to which he was tipped off as Clark Kent), throwing the abuser against the wall with a cry of, “You’re not fighting a woman, now!” Later, he apprehends some gangsters who have kidnapped Lois, chasing down their car and destroying it by hand. In all cases, Superman’s powers dictate the way he does things — hoisting cars and people above his head, facing down bullets and knives without flinching, overcoming opponents by pure brute force. However, those powers do not dictate what he chooses to do. After all, Hugo Danner had those same powers, but he sure never dressed up and fought crime.

Superman decides, according to the origin, that “he must turn his titanic strength into channels that would benefit mankind.” The reason for this decision is not made clear, and it’s difficult to discern whether Clark Kent would be a do-gooder if not for his powers. But those stories, of protecting the innocent and punishing the guilty, speak to a deeply held desire within us, certainly within Hollis Mason. They remind him of “juvenile fantasies” like saving pretty girls from bullies, or teachers from gangsters, and lead him to wonder whether he could make those fantasies come true.

Here is where the “basic morality of the pulps” comes into play. Doc Savage swore to “think of the right and lend my assistance to all those who need it, with no regard for anything but justice.” The Shadow admonished us that “the weed of crime bears bitter fruit.” And by issue #6 of Action Comics, Superman’s raison d’etre had coalesced into some version of:

Friend of the helpless and oppressed is SUPERMAN, a man possessing the strength of a dozen Samsons! Lifting and rending gigantic weights, vaulting over skyscrapers, racing a bullet, possessing a skin impenetrable to even steel, are his physical assets used in his one-man battle against evil and injustice!

Nite Owl’s abilities are very different from Superman’s, but his mission is not. He surely didn’t have the strength of a dozen Samsons, but what he did have was a deeply rooted desire to help the helpless and oppressed, and to fight against evil and injustice. He waged this battle with nothing more than his fists, really a far braver battle than Superman’s, as Mason was so much more vulnerable. And yet, wasn’t Hollis Mason doing this already as a policeman? Why, after a day of fighting crime in regulation blue, did he need to dress up as an owl to fight crime at night?

Well, for one thing, there’s a clear appeal in Superman’s directness. No policeman could have saved Evelyn Curry — the time was too short and the barriers too great. As for the wife-beater and the kidnappers, a cop might have stopped them, sure, but he would be denied the visceral satisfaction of meeting their violence with violence. And as for going to Washington and threatening lobbyists, forget it. Superman was unconstrained by rules and regulations, and in his identity as Clark Kent, could seek information and situations that would allow him to do his thing. Hollis Mason never comes out and says so, but I think it’s safe to imagine that he might have longed for the kind of freedom enjoyed by Superman in his battle against evil and injustice.

Still, that longing may have remained unexpressed if not for Hooded Justice, who was the first to tie the strands from Action Comics #1 into a shape that could exist in Mason’s world: physical power, fighting evil, with a concealed identity. Mason sees Hooded Justice as “the first masked adventurer outside comic books,” and says, “I knew I had to be the second.”

Last time, I cited Adela Yarbro Collins talking about apocalyptic fiction as a way to “overcome the unbearable tension perceived by the author between what was and what ought to have been.” In Superman, and Hooded Justice, Mason sees a different path to overcoming that tension. He doesn’t have to destroy the world. He doesn’t even have to destroy himself — just hide himself a little, and create a persona that allows him to author the change he wishes to see.

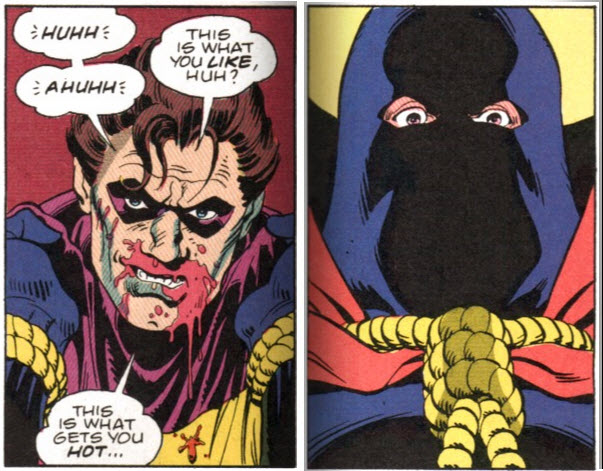

Yet in doing so, a different tension arises. Mason makes a point of mentioning his relief about what is left out of Action Comics #1: darkness, sexuality, moral ambiguity. And yet Hooded Justice has all these things in spades. Far from “bright, primary colors”, he’s draped in darkness (with, okay, a long pink cape for some reason.) He’s not the least bit afraid of devastating violence, crippling and hospitalizing his victims. And in his baleful gaze at the Comedian’s nasty jibe, it’s clear that this man is well acquainted with the “repressed sex-urge”, an urge deeply entangled with his darkness and menace.

Embedded within Hollis Mason’s dual inspirations is a contradiction. The very things that Mason was so relieved to see absent from Superman’s bright, primary-colored world, are there from the beginning in his own. From what we can see of his career, he seems to have tried to provide the counterpoint, to project a chaste and cheerful image — the perfect Silver Age crimefighter. And yet darkness and ambiguity are all around him, even in his compatriots the Minutemen, from the frightened, mentally ill Moth to the cruel, grinning Comedian. It only gets darker from there, and his namesake Nite Owl II is pretty much the post-Minutemen poster boy for repressed sex-urge.

It’s worth noting, though, that the early Superman isn’t entirely devoid of these things either. No, we don’t see a lot of sexuality coming from him, at least not when he’s in the tights — all his interactions with Lois seem to aim at getting rid of her as quickly as possible. Clark, on the other hand, does keep trying to date her, but self-sabotages his way out of every encounter, presumably to maintain his secret. This portrayal is in keeping with the audience Siegel & Shuster were aiming at: 10-year-old boys. The mysteries of sex are buried deep, only called dimly and distantly by images of Superman carrying helpless women, and being fawned over by Lois.

Darkness and ambiguity, on the other hand, are more present than you might expect, or at least so it appears when reading the stories today. In the first 12 issues of Action Comics, there’s nary a supervillain to be seen. Instead, Superman seems to be working through a list of social ills similar to Captain Metropolis’ bulletin board, except that his board has labels like “gambling”, “reckless driving”, “slum housing”, and “corruption in college football.”

He goes about these crusades in some unexpected ways. For instance, to fight slum housing he… destroys all the houses in the slums! “When I finish,” he declares, “this town will be rid of its filthy, crime-festering slums!” And indeed, as the helpful captions explain, “During the next weeks, the wreckage is cleared, emergency squads commence erecting huge apartment-projects… and in time the slums are replaced by splendid housing conditions.” Thanks, government of 1939!

Now here’s how he fights corruption in college football. He kidnaps a low-performing scrub from a college team, drugs him to keep him docile, and then replaces him on the team, thanks to the magic of “make-up grease-paint.” From there, he follows a rather complicated scheme of making the former scrub into a star, threatening to expose the corrupt coach of the opposing team, then winning the game on the scrub’s behalf while resisting the rotten coach’s hired thugs.

In fact, Superman is full of threats in those early days — he’s constantly suggesting he’ll kill or badly injure anyone who gets in his way. He gets a warmongering munitions magnate onto a boat heading into the war zone by saying, “Unless I find you aboard it when it sails, I swear I’ll follow you to whatever hole you hide in and tear out your cruel heart with my bare hands!” This is quite a long way from today’s morally pure Man of Steel. In fact, it’s a little closer to the second Nite Owl, in pain over Mason’s murder: “I oughtta take out this entire rat-hole neighborhood! I oughtta… oughtta break your neck, you… you…”

One more note about Action Comics. Just as issue #1 gave us the first superhero, issue #13 gave us the first supervillain: the Ultra-Humanite! Ultra was a reflection of Superman, right down to his name, but where Superman had strength, Ultra has “the most agile and learned brain on earth!” But, as he goes on to say, “unfortunately for mankind, I prefer to use this great intellect for crime. My goal? Domination of the world!!” Bald-headed and brainy, Ultra goes away a handful of issues later, to be replaced by Lex Luthor, for whom he was clearly the prototype.

Thus, an archetypal conflict was encoded very early on in the genre: brawn vs. brains. Somehow, brains frequently ended up on the evil side. As goes Action Comics, so go its successors… Watchmen included.

Next Entry: Housekeeping, and Some Notes on Method

Previous Entry: The End Of The World As We Know It

Leave a Reply