Si può? Si può? Signore! Signori! Be warned that the following post contains spoilers for Watchmen and for the opera Pagliacci.

Way back in my first entry, I called Rorschach “the funniest character in Watchmen.” Granted, that’s a pretty low bar to clear, but I stand by the assessment. Sometimes he’s funny on purpose (“Big Figure. Small world.”) and sometimes the humor just arises naturally out of his incongruity with the world around him, as when he drops Captain Carnage down an elevator shaft. Rorschach being Rorschach, there’s pretty much always a grim edge to his humor, and today’s topic is no exception.

Today we look at page 27 of Chapter 2, in which Rorschach tells (well, writes) a joke:

The web annotations have this to say about those panels:

The name of the opera Pagliacci literally means “clowns”, so Rorschach is mistaken if he thinks it is the name of a particular clown. The opera does, however, deal with a clown who must make others laugh although he is sad.

The annotators are quite right on the first point, but a bit reductive on the second, so let’s take the second point first, after taking in a little background.

Ridi, Pagliaccio

Pagliacci (which does indeed mean “clowns”) is an opera written circa 1891 by Ruggiero Leoncavallo. At that time, Leoncavallo was a fine piano player, a vocal teacher, and an aspiring composer who had been frustrated in his attempts to get his operas produced. In particular, he was focused on a work called I Medici, meant to be the first in a Ring Cycle-esque series, but focusing on the Italian Renaissance rather than Teutonic mythology. He was engaged with the Italian publishing house Casa Ricordi, but it had become increasingly clear that Ricordi had very little interest in producing Leoncavallo’s work.

In 1890, composer Pietro Mascagni premiered Cavalleria Rusticana, a one-act opera about love and murder among the Italian peasantry. The work met with “sensational success” (Leoncavallo: Life And Works by Konrad Dryden, pg. 34), and Leoncavallo, desperate for income, set about writing a work in the same vein. The result was Pagliacci, the story of a traveling commedia dell’arte troupe whose players find their own lives echoing the show they stage.

The main characters from the troupe are:

- Canio, a clown and head of the troupe

- Nedda, his wife

- Tonio, a hunchback clown

Tonio is in love with Nedda, who spurns his advances. Swearing revenge, Tonio finds Nedda’s secret: she is in love with the villager Silvio. Tonio leads Canio to find Nedda in an adulterous clinch with Silvio. Canio chases the villager in vain; Silvio escapes. Canio then demands that Nedda give him her lover’s name. She refuses, and their fight begins to escalate, but the time has come for the troupe’s show, and so they must stop and prepare their parts.

Here Canio sings the famous aria “Vesti la giubba” (“Put on the costume”), in which he agonizes over having to perform when his heart is broken by Nedda’s betrayal. The climax of this aria is one of the most famous in opera — appropriated everywhere from Seinfeld to Rice Krispies commercials. “Ridi, Pagliacco, sul tuo amore infranto” translates to “Laugh, clown, at your shattered love.” Thus ends Act 1.

Act 2 ushers us into the show-within-a-show. Nedda plays Columbina, who spurns the advances of Tonio’s character Taddeo. Columbina’s heart belongs to Arlecchino (Harlequin), and she wishes to conceal this fact from her husband Pagliaccio, played by Canio. As Canio approaches the stage, he hears Columbina address Harlequin using the very same words that Nedda had earlier used with Silvio: “Till tonight, and I shall be yours forever!” He drops his character and demands once more that Nedda reveal her lover’s name. Trying to salvage the show, she addresses him as “Pagliaccio”, prompting his furious arietta “No, Pagliaccio non son” (“No, I am not Pagliaccio”). His rage builds until he finally stabs and kills Nedda. Silvio tries to leap to her defense, and Canio kills him too. The play ends with the line, “La commedia è finita!” (“The comedy is ended!”)

I would argue that describing Canio as “a clown who must make others laugh although he is sad” is a bit wide of the mark. In fact, Canio never tries at all in the show to make anyone laugh — he breaks character immediately and escalates quickly to double murder. However, the sentiment of “Vesti la guibba” has become the main cultural takeaway from Pagliacci, and in that aria he does indeed cajole himself, “Laugh, clown, be merry… and they will all applaud! / You must transform your despair into laughter; / And make a jest of your sobbing, of your pain…” Of course, he fails to follow this self-advice, but its image remains indelible.

When Leoncavallo first wrote the libretto for this show, he titled it “Il pagliaccio,” which translates to “The clown.” However, he had made a friend of prominent baritone Victor Maurel, who saw a role for himself in Tonio, and who convinced Leoncavallo to pluralize the title to Pagliacci, so that Canio would not be the sole focus. With Maurel’s help, Leoncavallo presented the libretto to Casa Ricordi’s rival (and publisher of Cavalleria Rusticana) Edoardo Sonzogno, who immediately accepted the work. It was produced in May of 1892 to instant success, and has gone on to become a prominent part of the operatic canon, the only Leoncavallo work still widely performed.

Verismo

The title change wasn’t the only gift that Leoncavallo gave to Maurel. He also wrote a prologue especially for Tonio to sing. In this prologue, Tonio (or is it the singer, or Leoncavallo himself?) claims that the author of the show has endeavored “to paint for you a slice of life”, and that “truth is his inspiration.” Breaking the fourth wall and claiming to speak directly for the author, the prologue seeks to establish a connection between what you see on the stage and what you experience in your life: “Now, then, you will see men love as in real life they love, and you will see true hatred and its bitter fruit.” Moreover, he reminds the audience that the players themselves are fellow humans: “Mark well, therefore, our souls… for we are men of flesh and bone, like you, breathing the same air of this orphan world.”

This prologue became the manifesto of the verismo movement in opera, for which both Pagliacci and Cavalleria Rusticana became standard-bearers. Verismo was a reaction against the bel canto style, which had focused on songs at the expense of story — similar perhaps to superhero comics in the 1990s that focused on art at the expense of good writing. Verismo also steered operatic tradition away from loftier subjects — Wagner’s gods and heroes, or Verdi’s dukes, counts, and kings — and towards the dramas of ordinary people, such as peasants and clowns. As Pagliacci‘s prologue claimed, verismo wished to bring opera’s characters and players closer to its audience.

Now, at first blush this might seem like a ridiculous contradiction. The idea was to take opera, one of the most artificial and stylized storytelling forms ever, and somehow make it more realistic? The thing where every character is singing at the top of their lungs, accompanied by a full orchestra, instead of talking to each other? We were going to make that seem more like day to day life?

But really, is this any more absurd a proposition than injecting more realism into superhero comics? This would be the genre of storytelling where somebody somehow acquires supernatural abilities, and the way they handle this situation is to stitch together a crazy, colorful, skintight outfit and go out to “fight crime”, which generally means getting into fistfights with other people who have somehow acquired other supernatural abilities, and who decided to handle this by stitching more skintight garb and going out to, uh, do crime. Oh, and also pretty soon there are a whole bunch of the crimefighting people, and sometimes they fight each other, or join up into gangs and fight other gangs of the crime people, and bunches of them can fly without wings or punch down buildings or shoot laser beams from their eyes or maybe all that stuff at once, and a huge spectrum of other stuff too. And the world is always in jeopardy, always being saved. We were going to make that seem more like day to day life?

And yet, the power of verismo is that in such ludicrous and mannered forms, a little realism can go a long way! Sure, in Pagliacci everybody is still singing all the time, and the orchestra is still playing, but at least they’re not stiffly shuttling between recitatives and arias. They’re regular people rather than princesses or valkyries. In the context of the reigning operatic style, verismo was strong medicine, keeping opera a powerful and relevant cultural form into the early 20th century.

Similarly, Watchmen brings us a world where yeah, people dress up and fight crime, but only one of those people has any supernatural powers. The rest are just schmucks in Halloween suits. Moreover, those schmucks are fully realized, three-dimensional, flawed human beings rather than empty ciphers and walking metaphors. Not only that, the author has thought through the consequences of these powers and punch-outs, presenting a world where “superheroes” have been outlawed, and the one godlike figure heightens the tensions that could lead to nuclear annihilation, even as he’s the only one standing in the way of the powder keg exploding.

I would contend that one of the reasons Pagliacci resonates with Watchmen is that they share a similarity of purpose: to reinvigorate a constrained and formal genre by bringing it closer to earth, and therefore closer to its audience. They also share a structural approach — both of them feature a nested story that reflects and amplifies the main story. In Pagliacci it’s the commedia, and in Watchmen it’s the Tales Of The Black Freighter.

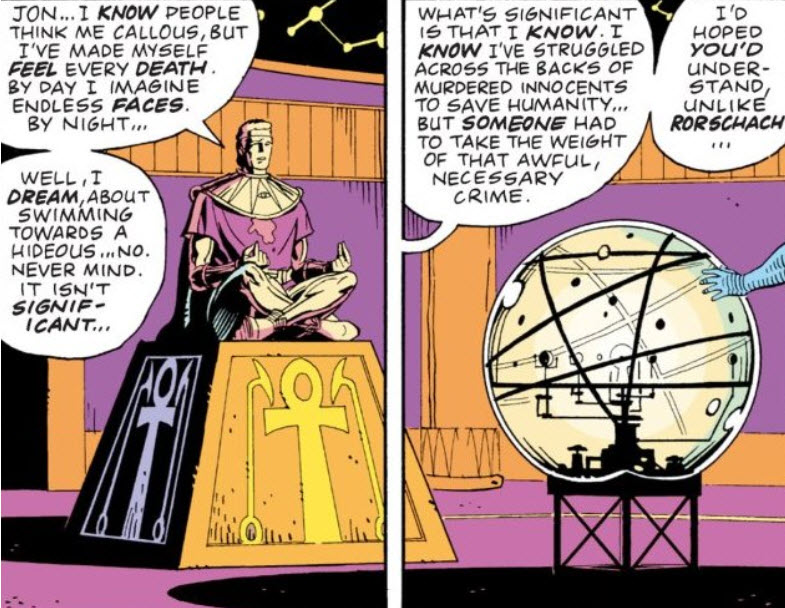

The plot parallels between Pagliacci‘s clowns and their characters are immediate and obvious from the beginning of Act 2, but Watchmen waits until Chapter 12 to fully reveal its hand. The pirate comic ends in Chapter 11 (shortly before its reader), with the viewpoint character finally realizing, “noble intentions had led me to atrocity.” He swims towards the Black Freighter itself, so that its crew could “claim the only soul they’d ever truly wanted.” This subplot takes its final bow on page 27 of Chapter 12, in which Ozymandias mentions that he has “struggled across the backs of murdered innocents to save humanity,” and that he dreams about “swimming toward a hideous…” before cutting himself off and saying, “it isn’t significant.”

But of course, we know it is significant — it signifies the parallel between the actions of Adrian Veidt and the actions of the Tales narrator. Both believe their crimes to have been “necessary”, and both think they are guided by “love, only love.” It is for us to see their folly, and as in Pagliacci, their tragic endings. Except that where Tonio or Canio might claim “La commedia è finita,” Dr. Manhattan would be quick to remind them that nothing ever ends.

Franco and Plácido

In 1982, just a few years before Watchmen, Franco Zeffirelli released a film of Pagliacci, based on his stage production at La Scala the year before, and starring Plácido Domingo as Canio. I watched that film as part of my research for this article, and a couple of things jumped out at me as comparisons to Watchmen.

The first is the clowns themselves. Before Tonio’s prologue begins, as the orchestra plays the overture, four clowns come out to entertain the audience. They are dressed in outlandish costumes. Their faces are obscured. They leap and bound athletically around the stage, enacting exaggerated dramas with each other and the audience. They are, in short, a bit reminiscent of superheroes. Both disguise their identities to assume personas in which they’re allowed to do things that would not be acceptable for civilians.

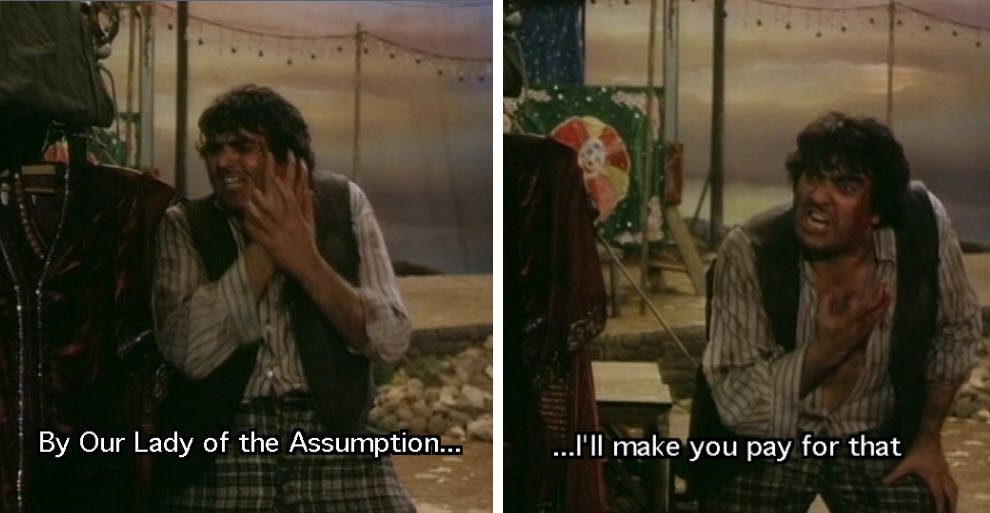

The other parallel is more overt and visual. In Nedda’s scene with Tonio, she at first laughs at his expression of desire, but when he becomes more aggressive, she must physically repel him. The libretto calls for her to do this with a whip, but Zeffirelli chooses to stage it differently. His Nedda is thrown by Tonio into her tent, from which she produces a knife and rakes it across Tonio’s face.

Tonio’s immediate reaction to this closely mirrors what we see of Eddie Blake when women attack his face in Watchmen.

Now, when Tonio is thus attacked, he responds by becoming an Iago-esque manipulator. (Leoncavallo was perhaps inspired by Verdi’s Otello, a huge success five years earlier, in which Victor Maurel had played Iago.) Blake prefers to meet violence with greatly escalated violence, attempting rape of Sally Jupiter and murdering his unnamed Vietnamese mistress. (He doesn’t strike back at Laurie when she throws her drink in his face, but then again it’s just a drink, and she is his daughter.)

Instead, if anyone is the Iago of Watchmen, it’s Ozymandias. Perhaps The Comedian’s lacerating words were the metaphorical equivalent of a knife to Adrian Veidt’s face. Perhaps Adrian’s stoic expression at the Crimebusters gathering, as Nelly’s display burns, is his equivalent of Tonio holding his cheek and swearing revenge.

I’ve been unable to find any clear evidence that Zeffirelli’s version of Pagliacci played on the BBC or anywhere else where Gibbons and/or Moore might have reasonably been able to see it. The timing is certainly right, and the film did play internationally (it was shown on U.S. television), but it’s difficult to establish whether The Comedian’s slashed face could possibly have been inspired by that of Tonio in this production. In the absence of such evidence, it must remain just a striking coincidence, and one more resonance between the works.

Reír Llorando

And yet, despite these resonances, the annotations are here to remind us that Rorschach’s invocation of Pagliacci seems to be rooted in error. There is no clown named Pagliacci, given that it’s the Italian plural of Pagliaccio. Moreover, Rorschach’s joke has been around for ages, appended to various famous clowns. (And a hat tip to Adamant on Science Fiction & Fantasy StackExchange, who tracked down many of these sources.)

Several sources associate it with Joseph Grimaldi, a pantomime artist of the early 19th century who created much of the modern clown iconography. Grimaldi’s memoirs were in fact edited by Charles Dickens (under the name “Boz”), and they do detail a life marked by trauma, including an incident of childhood abuse in which his tears very literally washed away part of his clown makeup. (Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, pg. 9) However, the doctor story does not appear in these memoirs — historian Andrew McConnell Stott cites it simply as an anecdote that “dates from the 1820s.”

Other versions of the joke mention the Swiss clown Grock, or just a generic clown. The oldest reference I’ve been able to find in writing (Stott’s assertion aside) dates back to the 1880s, and is in Spanish: Reír Llorando (“To Laugh While Crying”) by Mexican poet Juan de Dios Peza.

This version of the story is about an English clown called Garrik, who does not seem to be based on any particular historical figure. (I don’t think there’s any convincing reason to associate him with 18th-century Shakespearean actor David Garrick.) The clown has a long conversation about depression with a doctor, who suggests one treatment after another — travel, reading, love, etc. — before finally landing on “only by watching Garrik you can be cured.” To which, of course, the patient replies, “I am Garrik! Change my prescription.”

But while these Bestiary articles tend to focus mostly on what influenced Watchmen, this part of today’s story turns out to be about the influence of Watchmen itself. Because today the dominant form of the joke is as Rorschach tells it: “But doctor, I am Pagliacci.”

Google anything like “clown doctor joke” or “but doctor i am” and you’ll get hit after hit citing Pagliacci as the clown’s name, often referencing Watchmen directly. When Robin Williams died, Jeopardy! champion Arthur Chu hashtagged it #ButDoctorIAmPagliacci, then wrote a whole thing on HuffPost about it. There’s even a podcast called The Hilarious World Of Depression, in which the host interviews the many comedians who suffer or have suffered from clinical depression. That podcast’s theme song was written by Rhett Miller of Old 97’s, and it basically sets the old joke to music. The song’s title? “Pagliacci”.

So how does the name of an opera get substituted for the name of a clown in this old workhorse of a joke? Part of it may have to do with Smokey Robinson, who made a similar substitution in his 1967 song “The Tears Of A Clown”: “Just like Pagliacci did / I’m gonna keep my sadness hid.” But in the case of Watchmen, the larger part of it has to do with Dave Gibbons. In Leslie Klinger’s Watchmen Annotated book, Gibbons reveals that he just made a mistake while talking about the scene with Moore:

I remember that I told Alan [Moore] the story of the sad clown and used the name Pagliacci because i couldn’t call Grimaldi to mind at that moment. I didn’t correct it in the lettering for some reason but did try to get [director] Zack Snyder to correct it in the movie [Watchmen]. He stuck with the words of the comic!

So two artists working together (without the benefit of an all-knowing Internet to help them chase down references) tell a joke but make a minor error in it, one which happens to tie their work to an appropriate opera. Then that work gets turned into a movie by a director who fetishizes the text enough to keep the error in, and between the movie and the book, the mistaken version turns into the dominant form of the joke.

Now that’s the kind of irony that makes for a great punchline.

Next Entry: The Righteous With The Wicked

Previous Entry: Whose Mind Is Pure Machinery

Jason Dyer

I would have kept Pagliacci as the name in the film version too. The bonus subtext makes it more interesting that way (like making a scientific discovery by accident).

paulobrian

Yeah, I agree. I mean, Snyder *did* fetishize the text, but in this case the connection brings in extra resonance, so it’s all to the good.

trrish

Aha!, so that’s how you got to the THWoD! Well done, Paul. You are so good at this. I learn a lot reading them. And, I am somewhat partial to clowns, having married one.

paulobrian

Heh, it was sort of the other way around. THWoD is relevant to my interests (comedy, depression) and I was surprised and amused to find that its theme song is “Pagliacci” just as I was researching this article. Thank you for the kind words, and thanks for reading my stuff!