Ahoy there! Spoilers dead ahead, both for Watchmen and for the many versions of Mutiny On The Bounty. You’ve been warned.

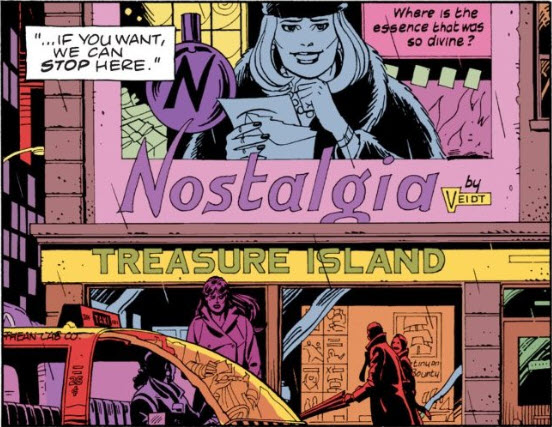

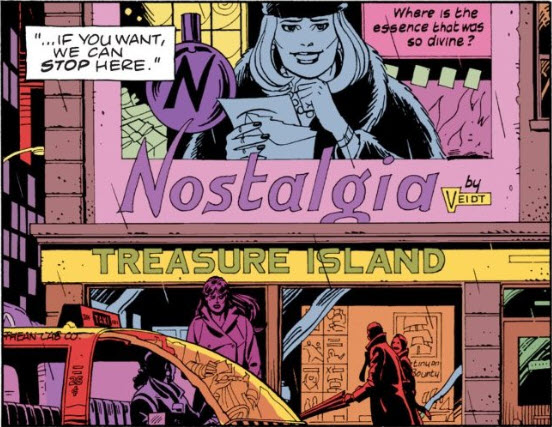

I’ve got mutiny on my mind today because of this panel:

Actually, let’s zoom in on the bottom right corner of that panel:

The web annotations zoomed in on this spot as well, pointing out:

Also, note the comic “Mutiny on the Bounty” in the comic shop’s window, and the prevalence of pirate themes in the covers of the other comics. One comic has an “X” in its title, perhaps a sly reference to the “X-Men” comics of the real world. (The title “X-Ships” appears on a comic early in Issue 1.)

As much as I love to chase down every little reference, I won’t be writing a post on the X-Men and Watchmen — the connection is just too slight. The annotators are probably correct that “X-Ships” references X-Men, given that X-Men comics were at their peak of popularity when Watchmen was being written. Since pirate comics dominate the Watchmen world, X-Ships are their likely X-Men analog, but that strikes me as just a little joke, not the kind of intertextual allusion that this series digs into.

Mutiny On The Bounty is another matter. I would argue that this reference illuminates several levels of Watchmen. But before exploring that, let’s talk for a while about the story itself.

Making a Mutiny

One might ask first why Mutiny On The Bounty would be a pirate comic at all. Sure, it’s a nautical tale, but it’s hardly Treasure Island. Where are the pirates?

Well, it turns out that most versions of the story refer to the mutineers as pirates. They may not be one-legged parrot-keepers plundering merchant ships for doubloons, but they do in fact take the ship they had crewed, and anyone who seizes one of His Majesty’s ships becomes a pirate in the eyes of the British Navy.

The historical facts of the mutiny are as follows. The cutter Bounty was commissioned to collect breadfruit plants from Tahiti and bring them to the West Indies, in hopes that the tree could be cultivated as a food source for plantation slaves on those islands. Lieutenant William Bligh commanded the ship, which had been specially fitted out to hold six hundred plants. This remodeling shrank the living space of everyone on board, making an already uncomfortable sea voyage even more difficult.

Bligh’s original plan was to travel west from England to Tahiti, rounding Cape Horn on the way to Oceania. However, bureaucratically-imposed delays meant that the Bounty didn’t start sailing until the weather had turned impassable south of the Cape. Bligh, a disciple and former navigator to the revered Captain Cook, was an immensely confident sailor, but this circumstance thwarted him. He tried for nearly a month to get through, but eventually gave up and headed east, stopping to re-provision the ship at Cape Town, then sailing onward, south of Australia (called New Holland at the time) and New Zealand to Tahiti, where he landed in late October of 1788.

By all accounts, Tahiti was a sailor’s paradise. It had gorgeous weather, stunning landscapes, abundant food and water, and friendly indigenous people, with a far less sexually inhibited culture than that of 18th century England. The Bounty‘s botanical mission obliged its crew to stay on the island for several months, so that they could secure agreements with various native chiefs to take plants from their groves. In the process, many members of the crew also formed relationships with native women. The initial delay in launching the ship also meant that it must wait out the western monsoon season, which wouldn’t end until April. Thus began a five-month tropical sojourn for the ship and its crew.

On April 5, 1789, laden with over 900 breadfruit plants (Bligh had somehow made room on the ship to store even more than planned), the Bounty set sail from Tahiti. Their orders were to pass through the Endeavour Straits (now known as the Torres Strait) between Australia and New Guinea, in hopes that Bligh’s navigation and surveying skills could help define a safe passage for future missions. But the Bounty would never travel through those Straits.

At dawn on April 28, master’s mate Fletcher Christian and several accomplices awakened Bligh. They dragged him, clad only in a nightshirt, up on deck. The mutineers ordered Bligh into the Bounty‘s launch, where he was joined by seventeen loyalists. Several others remained on board the Bounty, either detained by the mutineers for their skills, or simply unable to fit into the already dangerously overburdened launch.

Bligh and his crew traveled over 3,600 miles in an open boat, from the site of the mutiny to the island of Timor. They endured extraordinary hardships of starvation and exposure, and they did in fact pass through the Endeavour Straits. Bligh’s entire crew survived this journey, with the exception of quartermaster John Norton, who was killed by hostile indigenes on an island where the crew had attempted to re-provision. After reaching the Dutch settlement on Timor, Bligh and company found their way back to England, where his journey was rightly hailed as an astonishing act of seamanship.

Meanwhile, the mutineers and remaining loyalists splintered. Some stayed on Tahiti, taking wives and having children. These men were collected several years later by the British vessel Pandora, which itself then sank in the Endeavour Straits. The survivors of that shipwreck took the remaining prisoners back to England, where they were court-martialed. Some were acquitted, some were found guilty but pardoned by the crown, and some were hung. The rest of the mutineers had fled to the remote Pitcairn’s Island. The British never caught these men, but they fell out among themselves and the Tahitians they had brought along, such that there was only one Bounty crew member remaining when an American vessel stumbled upon the island twenty years later. The descendants of these mutineers and Tahitians live on the island to this day.

What doomed the Bounty? What brought Fletcher Christian and his fellow crewmen to such an emotional extreme that they were willing to become pirates and set eighteen men adrift to what must have seemed like certain death? What does this mutiny mean? The answers to these questions have been much disputed, and their portrayals over the years are a saga unto themselves.

Story vs. Story

Bligh returned to England in March of 1790. He was court-martialed — mandatory for any captain who lost his vessel — and exonerated of all charges. Within a few months, he published his Narrative of the Mutiny, which in fact devoted a scant six pages to the mutiny itself, and another eighty to his open-boat journey. He declined to speculate on Christian’s motivation, saying only that he heard the crew cheering “Huzza for Otaheite” (“Hooray for Tahiti”) as the launch pulled away. (The Bounty Mutiny, pg. 10) Based on this narrative, England hailed him as a hero. He met the king, was promoted twice, and subsequently set sail on another breadfruit expedition, departing in August 1791 aboard a ship called the Providence.

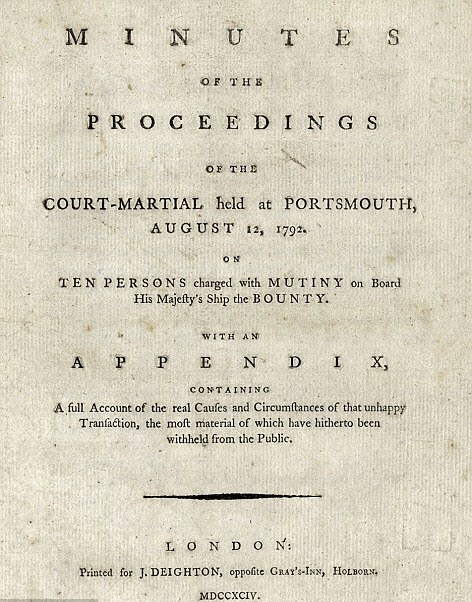

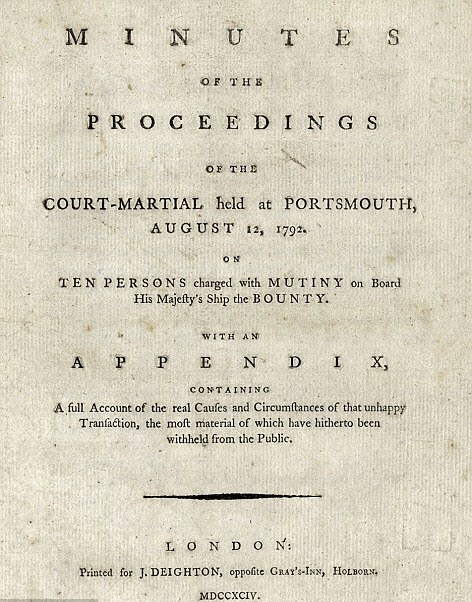

Meanwhile, the Pandora had launched to capture as many mutineers as it could find, and its survivors returned to England in March of 1792. The prisoners’ court-martial that summer resulted in three hangings, four acquittals, and two royal pardons.

After the dust settled, the first competing narrative began to take shape. Fletcher Christian’s brother Edward, a Cambridge-educated lawyer, took it upon himself to interview all returned survivors of the mutiny, both those who had journeyed with Bligh and those who had been captured by the Pandora. He released a pamphlet with a partial transcription of the court-martial, and an extensive appendix (The Bounty Mutiny, pg. 67), which used those interviews to condemn Bligh as a tyrant and show Fletcher Christian as a noble soul who rebelled only as a last resort under intolerable circumstances.

That argument saw print in 1794, in the midst of a historical moment ripe for such a story. The French Revolution had overthrown the monarchy there just a few years prior, and the American colonies had rebelled less than fifteen years before that. Individuals longing for freedom and deposing tyrannical authorities were the cultural order of the day, and Romantic poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge found an avatar in Fletcher Christian. In addition, the Jacobins of the French Revolution exalted the philosophies of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose notions of mankind’s goodness in a “State Of Nature” were easy to overlay upon the Tahitian indigenes, thus providing another justification for men who wanted to leave a corrupt civilization and live amongst “noble savages.”

Bligh returned in 1794 and exchanged retorts with Edward Christian, but the sailor was ineffective against the lawyer, and the damage to Bligh’s reputation would never be fully undone. The discovery of survivors on Pitcairn’s Island in 1808 excited public interest again, and launched a new wave of Bountyphilia. Sir John Barrow published an account in 1831 which upheld the image of Bligh as an overbearing martinet. Barrow was a family friend of Peter Heywood, one of those captured by the Pandora and later pardoned by the crown. In 1870, Heywood’s stepdaughter Lady Diana Belcher published another version of the story, again justifying Heywood and Christian against a Bligh portrayed as ever more villainous.

There were theatrical plays made of the story, but it didn’t receive the full novelistic treatment until the twentieth century, when Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall published Mutiny On The Bounty in 1932. For dramatic purposes, they created the fictional viewpoint character Roger Byam, who stood in for Heywood on the Bounty‘s crew. Nordhoff and Hall grounded their story in many historical facts, but also invented details to corroborate Bligh’s cruelty and Christian’s nobility. There was in fact a full Nordhoff and Hall Bounty trilogy — book two followed Bligh’s voyage and book three the life of the mutineers on Pitcairn’s Island — but it was Mutiny On The Bounty that caught the public’s imagination most. Hollywood took notice.

Mutiny On The Big Screen

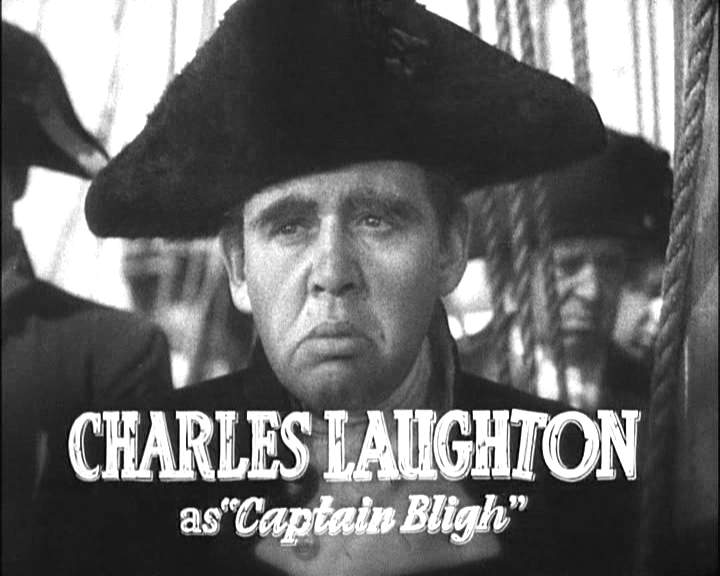

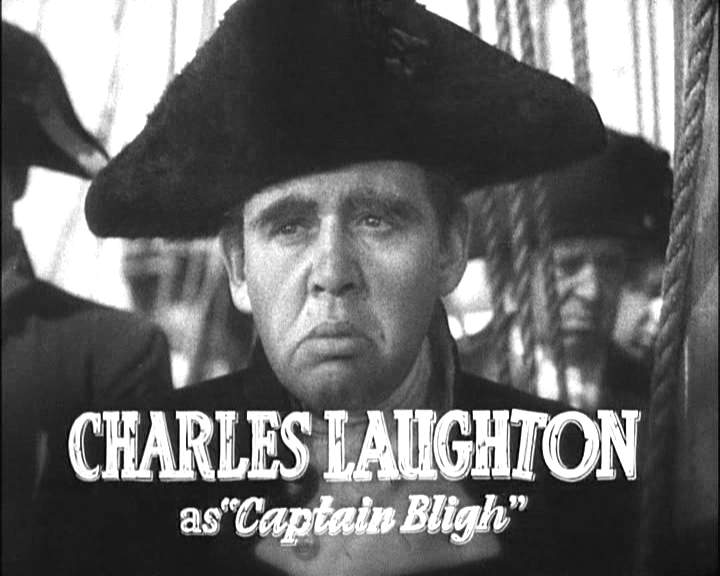

MGM released its film Mutiny On The Bounty in 1935, directed by Frank Lloyd and starring Clark Gable as Fletcher Christian, Charles Laughton as William Bligh, and Franchot Tone as Roger Byam. MGM’s movie directly adapted Nordhoff and Hall’s novel, and it was a smash success, capturing the 1935 Academy Award for Best Picture. Gable, Laughton, and Tone were all nominated for Best Actor, splitting the vote and leading to the creation the next year of the “supporting role” Oscars.

The Lloyd Mutiny film amplified every exaggeration of Nordhoff and Hall’s, and layered in quite a few new ones. For instance, in the novel Byam witnesses another captain order a man flogged, and the punishment kills its target. The captain then orders that the flogging continue until the full complement of lashes have been delivered to the bloody corpse. (This scene has no basis that I can find in the surviving historical evidence surrounding the Bounty.) In the movie, it is Bligh who gives that order, and stands watching with satisfaction until the grisly punishment is complete. In historical fact, Bligh had a fastidious aversion to flogging, and tried to avoid it as much as possible.

Similarly, where Bligh’s actual log records his disgust with his surgeon Thomas Huggan, who he saw as a “Drunken Sot” (The Bounty, pg 84), Nordhoff and Hall give the surgeon a wooden leg (nodding to Stevenson, I suppose) and an ever-present bottle of brandy. Lloyd’s film has everyone on board calling the surgeon “Old Bacchus”, introduces him by hauling him aboard in a net, and turns Dudley Digges loose on him with a ridiculously broad performance.

Then there are the scenes entirely invented for the film. Laughton’s Bligh keelhauls a man, which happened in neither the book nor the historical record — the practice had been outlawed in the British Navy for decades. Gable’s Christian turns to mutiny after some crew members are unjustly imprisoned, but in the book, he simply bristles at being unfairly accused of theft. Finally, Lloyd’s film shows Bligh himself in command of the Pandora, unlike the book which correctly depicts its captain as Edward Edwards. Aside from these story changes, the simple act of casting Gable as Christian and Laughton as Bligh tells the audience very clearly where its sympathies should lie. Laughton in particular turns in a marvelous performance as a corrupt, blustering villain.

All these changes are made for the sake of drama, and they work very well, but their dramatic logic is simple indeed. Every uncertainty and nuance of the historical record, already greatly flattened by Nordhoff and Hall, gets sanded down into a stark story of good versus evil, of corruption overthrown by force. Just as Hollis Mason observed about Superman’s relation to the pulps that preceded it, Lloyd’s film (released three years before the debut of Superman) similarly removes the last of its predecessors’ darkness and ambiguity in favor of a basic, boiled-down morality.

Interestingly, after 1935 the pendulum began to swing back in the other direction. In 1962, Carol Reed and Lewis Milestone directed a version of the story starring Marlon Brando as Christian and Trevor Howard as Bligh. When Gable clashed with Laughton, you knew who to root for, but in the 1962 version, no character is particularly sympathetic. Bligh is awful, of course, a sociopath who uses others to accomplish his mission without for a moment considering their experience or humanity. But Brando’s preening and simpering Christian is also far from admirable. He’s foppish and contemptuous from the start, only goaded into mutiny by the character of John Mills (played by Richard Harris) as the devil on his shoulder. Even the Tahitians come across as weirdly unpleasant. By making everyone a villain (or anti-hero), the 1962 version mostly indicts the system — showing the impossible position into which the men are put. They are utterly at the mercy of Bligh, who cares nothing for their lives, but they will also die if they go against him.

There was one more filmed version of the story: 1984’s The Bounty, starring Anthony Hopkins as Bligh and Mel Gibson as Christian. This is by far the most historically accurate Hollywood depiction. Bligh and Christian, rather than being exaggerated villain & hero, or exaggerated villain & anti-hero, come across as three-dimensional humans, both deeply ambitious and deeply flawed in their own ways. This version still injects a bit of fiction, giving Bligh a strangely burning desire to circumnavigate the globe, and very subtly suggesting that he had a homosexual attraction to Christian, but in general it redeploys historical detail to reshape the simple good and evil story that Mutiny On The Bounty had become, into a nuanced tragedy of complicated people at a complicated historical moment.

Here at last we can return to Watchmen. Tracing the path of Bounty portrayals up through 1935 makes it clear that they constitute a kind of Watchmen project in reverse. Where Moore and Gibbons started with the simplistic Golden Age and laid in layer after layer of realism, humanity, and grit, every new version of the Bounty story stripped those layers away, culminating with the Lloyd film’s simplistic depiction of hero Christian versus villain Bligh. This depiction has never left the public imagination — “Captain Bligh” is still a synonym for a tyrannical and oppressive leader.

Leslie Klinger’s annotations assert that the Watchmen panel in question shows a “vintage poster in the window for the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty“. This is a little different from the web annotations’ suggestion that we’re seeing a Mutiny on the Bounty comic, but either way it makes sense that the poster would reference the 1935 version of the story, since that was the most successful and culturally impactful version ever made. Not coincidentally, that version is the most simplified, melodramatic adaptation of the story known to mainstream audiences. Its appearance in the comic shop window is the pirate equivalent of Action Comics #1.

Watchmen itself, on the other hand, is more like the Hopkins/Gibson Bounty movie — a movie that happened to emerge in 1984, when Watchmen was being written. By placing Mutiny On The Bounty in a window of the Watchmen world, Moore and Gibbons give us a window into how narratives and genres can evolve over time, and they reflect their own project in doing so.

Mutineers

Watchmen itself was a kind of mutiny. It rebelled against the established order in mainstream comics, striking at the injustice and hypocrisy beneath the cultural authority of superhero narratives, narratives that had claimed the mantle of justice and righteousness for themselves. Like many mutinies, its results have been mixed — superheroes’ cultural authority is stronger than ever, as Marvel’s box office receipts will tell you, but at the same time they were forever changed by Moore’s story. That story is full of mutineers, too.

There’s a quote in Nordhoff and Hall’s novel that’s particularly apropos to Watchmen. It comes in a reflective moment, as Byam describes Fletcher Christian:

His sense of the wrongs he had suffered at Bligh’s hands was so deep and overpowering as to dominate, I believe, every other feeling. In the course of a long life I have met no others of his kind. I knew him, I suppose, as well as anyone could be said to know him, and yet I never felt that I truly understood the workings of his mind and heart. Men of such passionate nature, when goaded by injustice into action, lose all sense of anything save their own misery. They neither know nor care, until it is too late, what ruin they make of the lives of others.

That notion, that a supposed hero fighting for justice could ruin the lives of innocents, comes entwined in Watchmen‘s DNA, while the quote also captures the spirit of several characters. Certainly it applies to Rorschach, and no less to Ozymandias. Though not born from a passion for justice, detachment from human costs and consequences characterizes several others as well: The Comedian, Silk Spectre I, and of course Dr. Manhattan. Then there’s the narrator from Tales Of The Black Freighter, who certainly can be said to have lost all sense of anything save his own misery. The Black Freighter itself, as discussed earlier in this series, evokes Pirate Jenny, a true rebel against oppressive authority, who plots gleefully to slaughter them all.

The panel we’re examining juxtaposes two mutinies on the same page. Janey Slater rebels against Jon and the dominant story of her past by vilifying Dr. Manhattan to Nova Express. Laurie, as she walks by the Treasure Island window, is in the midst of defying the will of a government that just wants her to “get the H-bomb laid every once in a while.” In the government’s eyes, her mutiny may have doomed the ship, as “the linchpin of America’s strategic superiority has apparently gone to Mars!”

That same government enacted the Keene Act outlawing costumed vigilantes, and that’s an authority against which there are plenty of mutineers. Rorschach, of course, rebels from the start, killing a multiple rapist and using the body to deliver his note of refusal to police headquarters. Nite Owl and Silk Spectre join the mutiny many years later, as they suit up and go out on patrol in Chapter 7. Meanwhile, Ozymandias has been rebelling in secret all along, pretending to acquiesce to authority even as he engineered his fake doomsday plan, without a care for the ruin he’d make of the lives of others.

Story Vs. Story, Revisited

Ozymandias’ plan comes down to storytelling. That’s why he recruits writers and artists — he knows that his “practical joke” must be a convincing enough story that every nation in the world will believe it. But he’s not just telling a story to the world. Like Captain Bligh, his story to the world is also a story to himself, one that casts him in the role of hero and savior, the only one brave and capable enough to save the lives in his charge, despite all opposing forces. Like Bligh, he has no doubt that his narrative will prevail. Like Bligh, he will have an unexpected competitor.

Rorschach, through his diary as submitted to the New Frontiersman, will become the Edward Christian to Ozymandias’ Bligh, presenting an alternative version of events that radically recontextualizes the story known and accepted by the public. Like Christian, Rorschach has his own agenda and values that influence his version of events. I don’t mean to suggest that Christian has the truth on his side as Rorschach does, nor that Bligh intended a deception as Ozymandias does — only that the final level of drama in Watchmen comes from competing narratives, and invoking Mutiny On The Bounty can’t help but shine a light on how stories within Watchmen fight each other for dominance.

Rorschach and Ozymandias are the grand competing narrators of the work, but there are other narrative clashes within the book. For instance, every secret identity operates as a clash of narratives, in which a character keeps trying to smother the truth with a different explanation. In the case of a character like Hooded Justice, the competition becomes even more complex, especially as it’s reflected at the reader’s level. We never learn who Hooded Justice really was from the text itself, but we do get speculations from Hollis Mason. These speculations seem reasonable enough, but they are all we get from the text until Chapter 11, when Ozymandias tells his story of investigating Hooded Justice’s disappearance.

Veidt wonders: “Had Blake found Hooded Justice, killed him, reporting failure? I can prove nothing.” Now we as readers must evaluate several strands. There’s what we know about Rolf Müller, which comes strictly from the pages of Under The Hood — circus strongman, East German heritage, disappeared during the McCarthy anti-superhero hearings, found later shot through the head. Then there’s what we know about Hooded Justice — an early hero who came into serious conflict with The Comedian at least once. Then there’s what we know about Blake himself — someone who wouldn’t hesitate to execute an enemy and throw him in the ocean. These strands seem to present a coherent picture, but in all cases they are presented through the lens of another character telling a story for a particular purpose, some of whom may be more trustworthy than others. As with the history of the Bounty, we are left to discern the truth for ourselves.

Also like the Bounty, Watchmen itself has endured numerous forces trying to shape its story from the outside. Zack Snyder’s film version was loyal in its fashion, but also changed the story and the tone in ways both necessary and unnecessary. DC gave us Before Watchmen and Doomsday Clock, which tried to extend the Watchmen world beyond the boundaries of the graphic novel, laying claim to canonical preequel and sequel stature by dint of being the original’s publisher, a claim which Alan Moore would vociferously dispute. Now, within just a few weeks of this post, HBO will debut yet another Watchmen story, this one a speculative sequel in TV series form.

All of these Watchmen versions wish to capitalize upon the status of the original, and to make us view it in a different light. They may not be mutinies, but at some level they are seizures, attempting to take a well-known ship in a new direction. Is that new direction fruitful? Is it necessary? Does it honor the mission? As befits the conclusion of Watchmen, that decision is left entirely in our hands.

Next Entry: Lonely Planet

Previous Entry: The Righteous With The Wicked