Happy New Year, and welcome to another year-end music list. Just to review, this is a year-end mix I make for some friends — full explanation on the first one I posted in 2010. It’s not all music from 2018 (in fact, my backlog of music to listen to pretty much guarantees that nothing on here is timely.) It’s just songs I listened to this year that meant something to me.

For the first time, I’m linking to a Spotify playlist for these rather than linking each song, because for almost the first time Spotify actually contains all the songs in the mix. I’m also going back and adding these playlists to previous mixtape posts and to Album Assignments posts, because I like the idea of the music being available right in the post when I’m writing about music. Anyway, I hope you enjoy it!

1. Elvis Costello – The Comedians

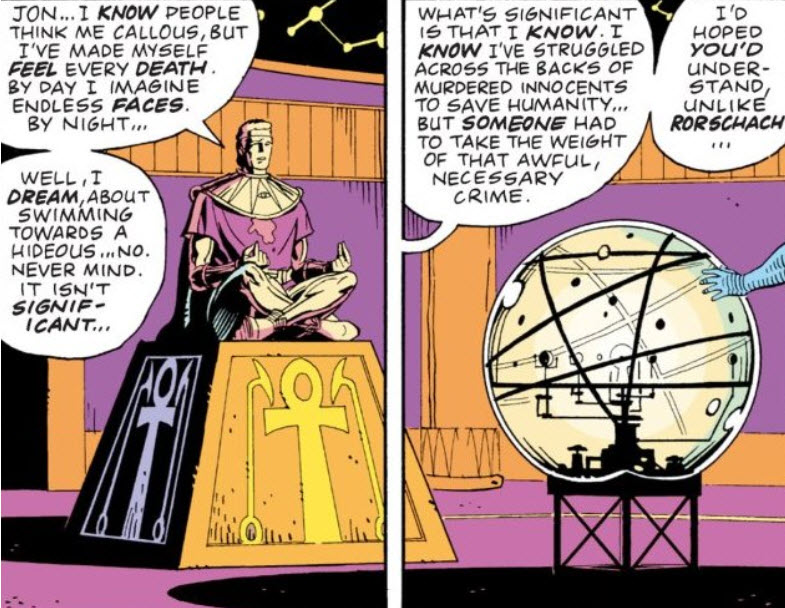

Over the past few years, I’ve mentioned how the Album Assignments project with my friend Robby has influenced my music listening, and consequently the makeup of these mixes. However, sometimes my other project — The Watchmen Bestiary — can have a big influence too. Alan Moore quotes this Elvis Costello song in Chapter 2 of Watchmen, and I wrote about the connections between them in 2017. I also bought this album, Goodbye Cruel World, on CD at that time, but the delay inherent in having a big stack of CDs to listen to (and interspersing them with a podcast, an audiobook, and periodic iPod shuffles) means that I didn’t listen to it until 2018. Costello doesn’t have many good things to say about this album himself, but I’ve come to like this song quite a bit — possibly Stockholm Syndrome. Its weird, off-kilter time signature, the typically clever Costello wordplay in its lyrics, and of course the Watchmen connection make me fond of it. And really, “a toast to absent friends” couldn’t be better as a title for this collection, since I make it for our friends across the ocean. Cheers!

2. The Killers – Jenny Was A Friend Of Mine

As I wrote in my post on Hot Fuss, I think this is an amazing debut song. That bass line grabs me every time, and Brandon Flowers’ voice could bring thrilling drama to absolute nonsense (and has.) Listening to this song was my favorite part of doing the deeper dive into Hot Fuss.

3. Rilo Kiley – Does He Love You?

Speaking of intensity (and of Jenny), I can’t get enough of Jenny Lewis’ vocal theater on this song. She takes us through a full three-act play, complete with twist ending, and plays the character’s arc to the hilt. She starts loving and innocent, then gradually introduces notes of contempt and abandonment. When she comes back to a softer tone, her earlier aggrieved self-pity makes her sound distant rather than supportive, and when she finally reveals the connection between her “married man” and her interlocutor’s husband, she couldn’t sound more disgusted with EVERYTHING. By the time she’s returning to “let’s not forget ourselves”, her vocal is distorted and venomous, and the emotional strings swirl around it, until those strings are all that’s left. Just marvelous.

4. The Go-Go’s – Our Lips Are Sealed

Now here’s a more fun take on secrets. I loved the chance to dissect why I think this is such a perfect pop song, and every single time I hear it I can’t help but be uplifted and opened. And my god, how I love that drum break at 1:51. Air drums every time.

5. Stevie Nicks – The Dealer (demo)

Stevie did an album called 24 Karat Gold a few years ago, in which she took a bunch of old demos (most of which had been circulating in the fan community for decades) and recorded them with a professional band. This was wonderful, no doubt, but there are also just some unavoidable differences between Stevie in her 30’s and Stevie in her 60’s, and they felt pretty glaring on certain songs. “The Dealer” has been one of my favorite unreleased Stevie songs forever, and the version on 24 Karat Gold didn’t feel like it held up in comparison to the demos. Lucky for me, she re-released her first two albums, remastered with a bunch of extra tracks, and this polished-up version of an old “Dealer” demo showed up with the Bella Donna remaster. This was the best of both worlds for me — all the power and energy of the initial recording, professionally released and cleaned up.

6. The Go-Go’s – I’m With You

I was inspired to assign Beauty And The Beat to Robby after listening to a re-release of Talk Show, the album on which this song appears. I’ve always been deeply partial to The Go-Go’s, not just for their fun but for the musical surprises they always delivered. This song feels like one of those hidden gems — I love the strange minor key melody, paired with such fiercely devoted lyrics. I think this is one of the best things Jane Wiedlin ever wrote (in this case with Gina Schock as co-writer), and it’s the first of a few unabashed love songs in this collection.

7. Wilco – Remember The Mountain Bed

I spent a week or two with Mermaid Avenue Volume 2 this year, and became infatuated with this song. Woody Guthrie’s lyrics paint an incredibly vivid picture of memories of a bygone love — indelible images like “Your stomach moved beneath your shirt and your knees were in the air / Your feet played games with mountain roots as you lay thinking there.” But while the lyrics thrum with life, it’s Tweedy’s voice and music that send them straight into my heart. “I see my life was brightest where you laughed and laid your head” makes me want to cry with the poignancy of it. This song is exactly why I decided I finally needed to learn more about Wilco. (I’ll be coming back to that later.)

8. Fleetwood Mac – Brown Eyes (alternate version with Peter Green)

Wrapping up the love song section is this astounding (to me) alternate version of a lovely Christine song from Tusk. This song has completely different lyrics from the album version — for one thing, it doesn’t mention brown eyes at all. Where the released version is full of Christine’s trademark ambivalence, this one is sweeter and purer. Obviously I’ve known the Tusk version for ages, so this one felt very powerful to me, especially the way Peter Green’s spooky guitar creates a gorgeous, haunting tone that ties it back to the earliest days of Fleetwood Mac.

9. Eric Clapton – Motherless Children

This is one of those songs where the tragic words lay inexplicably atop a joyful foundation. It’s one of my favorite Clapton riffs, and the whole feel of the thing is just a groove party. So why the lyrics about losing a parent? Beats me — all I know is I love all the other pieces of it, no matter what he’s singing about.

10. Talking Heads – Crosseyed and Painless

More from the joyful dancing division — I listened to Remain In Light quite a bit at home during part of this year, and the whole thing just made me dance around the house. Like “Motherless Children”, the words to this one aren’t exactly sunny — and in fact I’m really not sure what they’re even about — but man oh man the Talking Heads had the keys to funky rock castle during this period.

11. Wilco – I am trying to break your heart

So, I wrote about this one at length in my Yankee Hotel Foxtrot post, and would just be repeating myself here by breaking it down. I’ll just say that my experience of Wilco up to this point (on the Mermaid Avenue albums) had led me to a set of expectations that got completely demolished by the first 90 seconds of this song, in the best possible way. I love how the crazy surrealist shit leads your attention one way and lets you be shocked by gut-punches like “What was I thinking when I said it didn’t hurt?”

12. Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers – Change The Locks

But there’s a straighter path to devastating catharsis. At the beginning of my November to October listening period, I was still in the midst of a grief-fueled Tom Petty jag. I could have picked a lot of songs from his catalog, or even just from She’s The One, the album I ended up writing about. This one just hit me right as the right way to crash out of Wilco. It starts intense, and then cranks things up from there. I love the buildup in this song, the way it keeps cycling back to the same thundering chords, somehow gaining power each time until Petty hits us with that unbelievable scream. It’s not the first thing people usually mention when cataloging his many talents, but he was a hell of an expressive vocalist.

13. Muse – Madness

You want to talk about expressive vocalists? How about Matthew freaking Bellamy? You want to talk about buildup? How about this delicious song, with the thick synths, ever-increasing layered harmonies, elements gelling tighter and tighter until by the end he’s hitting operatic musical heights to go with the lyrical epiphanies? You want me to try summarizing a song using nothing but rhetorical questions? What better place to try a little experiment than on a Muse song?

14. Macklemore & Ryan Lewis (feat. Xperience) – Let’s Eat

Change of pace. My family was listening to this album during some of the time we were driving around on our Grand Canyon trip this year, and Laura cracked up at this song, so much so that we listened to it a bunch of times during that trip, and she brought home the printed lyrics from her job one day. Even now she’ll occasionally bust out with “I wanna be like Hugh Jackman / You know, jacked, man!” or “My girlfriend’s shaped like a bottle o’ Coke / Me, I’m shaped like a bottle o’ NOPE”. It’s become part of our family vocabulary.

15. Paul Simon – Wristband

Here’s somebody else who has a way with a humorous lyric. I listened to Paul’s Stranger To Stranger album this year, and this song really jumped out at me. I love how his wry and conversational tone turns serious at the bridge, and suddenly his funny little story reveals itself as a metaphor, illuminating inequality and lack of access as one of the central problems of our time. There’s those who have the wristband, those who don’t have it, and those who don’t even need it. Paul Simon is in the third group now, but he wants to talk to us about the second.

16. Stevie Nicks – After The Glitter Fades

Stevie grew up with plenty of privilege — her dad was an exec for various companies including Greyhound and Armour — but she wrote this song about her own stardom well before she had any kind of success. As I listened to the Bella Donna remaster this year, I loved every song, but this one struck me as particularly elevated by the remastering process. It’s a country song at heart, and the steel guitar blends beautifully with her vocal.

17. Joan Jett – I Love Rock N’ Roll

Right around that same era, another woman was breaking away from her band, to amazing success. This song compelled me from the very first time I heard it — well, saw it. This was the era when much of my music exposure came from MTV, and I loved the way she stood out as a woman totally owning what had seemed to me as a very male world. Before I knew anything about what feminism was, Joan Jett embodied for me what it meant to be a fearless and tough human being, questions of gender aside.

18. Stevie Nicks – Wild Heart

Fearlessness is fearlessness, and as you know if you’ve read much of my other stuff, Stevie’s blend of fierceness and vulnerability speaks to me like nobody else. I don’t know that I could ever pick a favorite song of hers, but this one is always in that top group. As with some of the other songs in this collection, I already broke it down in detail when writing about the album, so no point recapitulating that. Instead I’ll just say that this year was freeing for me in many ways, with breakthroughs happening on the professional, family, and world levels, and this song unfailingly takes me to the place where that freedom lives.

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.