[William Kuskin and Charles Hatfield deserve my heartfelt thanks for their generous and incisive feedback as this post was taking shape.]

I’d like to start today’s entry with a resounding endorsement for Love And Rockets. No, not the band, though they’re pretty good too. I mean the astonishing comic book series by Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, lovingly known as Los Bros Hernandez.

This comic ran from 1982 to 1996, and pretty much exemplified the alternative/indie comics scene at the time. (Los Bros have since picked it back up and continue publishing 1-3 issues per year.) Being born in 1970, I was a little young for L&R when it started, and spent most of my teens with my head ensconced in Marvel-world anyway. So while I’d heard plenty about the comic, I never read any of it until a few years ago. People, it blew my mind. See resounding endorsement, above.

For those of you who haven’t yet had the pleasure, here’s a little Love And Rockets primer. Gilbert and Jaime1 are the primary contributors, with occasional input from third brother Mario. The brothers work separately for the most part, each writing and drawing his own comics, and splitting the page count in a given L&R issue. Both of them draw some miscellaneous experimental comics in a variety of styles, but the bulk of their work focuses on continuing stories in a particular milieu.

For Jaime, that milieu is the Southern California punk scene, specifically a barrio nicknamed Hoppers, set in the fictional town of Huerta and based on Oxnard, California, where the brothers grew up. Gilbert’s continuing stories take place in Palomar, a fictional Latin American town so small and remote that in most of the early stories, the town doesn’t even have a single telephone.

Within these settings, each of them has built a dizzyingly rich cast of beautifully realized characters, in a variety of stories ranging from one-pagers to full graphic novels. I wholeheartedly recommend these comics, and I’m going to be spoiling various Love & Rockets storylines (between 1982 and 1986 or so), as well as the usual load of Watchmen spoilers. (And I guess a couple of 20th century Spider-Man spoilers too, as it turns out.) It’s really worth reading this stuff fresh, so I won’t mind a bit if you wait to read the rest of my post until you’ve caught up on some L&R yourself. Comic Book Resources has a great guide to getting started.

Heartbreak Soup

Now, then. Both brothers’ work is well worth absorbing, but we’re focusing on Gilbert today, for reasons that will become clear in a bit. The first Palomar story is called “Heartbreak Soup”, and it introduces us to many denizens of the town, including a group of childhood friends in their early teens: Heraclio, Israel, Jesús Angel, Sakahaftewa (“Satch”), and the partially disfigured Vicente. We also meet a whole bunch of others, including Jesús’s little brother Toco, midwife and bañadora (bath-giver) Chelo, impossibly pulchritudinous newcomer and rival bañadora Luba, and the boys’ peer Pipo, who has grown apart from them as her sexuality develops.

“Heartbreak Soup” tells a satisfying, self-contained story, but after it ends, the Palomar stories continue, and something interesting happens. The next episode, a little story called “A Little Story”, doesn’t continue from “Heartbreak Soup”, but rather jumps back about 4 years prior, to when Pipo was still happily playing with the boys, and Satch was the new kid in town. The next story, “Toco”, is another short piece, which takes place a few months prior to “Heartbreak Soup”.2

A more major, multi-part story called “Act of Contrition” follows these two. It skips forward about ten years from “Heartbreak Soup.” The boys are all adults, some of whom have left town, some of whom have stayed and married characters who were also children in “Heartbreak Soup.” Instead of one child, Luba now has four, and now she runs a cinema as well as a bath house. Not only that, we meet a new character named Archie, who knew Luba as a teenager, and we get flashbacks to her teen years, well before “Heartbreak Soup”, from both characters’ memories. Post-“Act Of Contrition”, the Palomar strips’ timeline sticks for a while with “Heartbreak” plus 10 years or so, but frequently interspersed with various flashbacks, from various perspectives, to various time periods.

What quickly becomes clear is that the Palomar stories in Love And Rockets won’t be following the traditional comic book approach of serializing an ongoing narrative. Instead, what we get are glimpses into one continuous, enormous, pre-existing story, as seen through the viewpoints of a large cast of characters, and skipping around in time at Gilbert’s whim. As comics scholar Charles Hatfield observes, “By opening such gaps between stories, Hernandez was able to sketch in the history of his characters gradually through interpolated flashbacks, a technique that became central to his work.” (Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature, pg. 89)

“Interpolated flashbacks” brings us at last to the v2.0 Watchmen annotations, which point out a fascinating parallel between one of the Palomar stories and Chapter 2 of Watchmen:

The structure of this chapter involves an exploration of Blake’s character in segments that alternate between a present-day storyline and flashbacks from five different other characters. The flashbacks are in fact in chronological order, from a flashback to his youth to a flashback to the recent past.

The structure of this chapter is therefore very similar to that of the story “The Laughing Sun”, by Gilbert Hernandez, which appeared in the comic Love and Rockets in 1984 (although there are only four flashbacks there). Since the Love and Rockets story predates Watchmen, it may have been an influence on Moore.

The parallel is undeniable, but can we reasonably claim that “The Laughing Sun” influenced Watchmen? Well, there is a bit of evidence. As the annotations indicate, the L&R story predates Watchmen, which establishes that it is possible for Moore to have read it before penning the chapter. Furthermore, we know that Moore has read and admired Gilbert’s work, because he tells us so in the introduction he wrote to Heartbreak Soup And Other Stories, the first US trade paperback collecting some of Gilbert’s Palomar comics. Moore even refers directly to “The Laughing Sun,” noting “the blood-thick camaraderie that leads to the desperate mountain trek” in its plot. (About which more in just a minute.)

This book was released in August of 1987. Watchmen #2 has a cover date of October 1986, and the final issue’s cover date is October 1987. Based on this overlap, I’d say it’s very likely that Moore wrote his appreciation of Gilbert in the midst of writing Watchmen.3 For as specifically as he cites details from them, the Palomar stories had to be fresh in his mind during that period. Now, would that connection have gone back all the way to issue #2? Who knows? Some of this stuff is ultimately irretrievable, but let’s take a look at the comparison and decide for ourselves.

Stacks of Flashbacks

“The Laughing Sun” is serialized over two issues of Love & Rockets. Like many post-“Act Of Contrition” Palomar stories, it takes place about 10 years or so past the “Heartbreak Soup” baseline. (I’ll abbreviate this baseline HBS, and cite different timelines in relationship to it, so the primary thread of “The Laughing Sun” takes place in HBS + 10 years or so.) The childhood friends from that story have grown up and spread out, but are brought together when they learn that Jesús Angel has fled to the mountains after an explosive conflict with his wife Laura. Heraclio, who still lives in Palomar, reaches out to Satch, Israel, and Vicente, who do not, and all four men come together to search the mountains for Jesús.

As the story progresses, each man remembers Jesús, with each flashback centering on some aspect of Jesús’s relationship with sexuality and women. After he gets the call from Heraclio, Vicente flashes back to a childhood episode with Jesús (HBS – 9 years or so), in which 5-year-old Pipo innocently exposed herself to the two boys, who were then shamed with visions of hellfire by Chelo after she walked in on the incident. On the car ride to the mountains, Satch remembers a preteen time (HBS – 2 years or so) where some older boys told him and Jesús about the Indian women in the mountains who don’t wear shirts — “They all walk around with their fuckin’ tetas out like it’s normal!” The boys swooned with envy of the Indian men.

Back in the present, the search in the mountains is arduous, for the weather is extremely hot. (The story’s title refers to how the sun seems to enjoy torturing the town like this.) Heraclio briefly passes out from heat exhaustion, and in the process flashes back to a memory from their teen years (HBS + 1 or so), which reveals Jesús’s crush on Luba, an unrequited affection that becomes a major theme for the character. The search goes on, through many a tribulation, culminating in Israel’s memory of himself and Jesús as adults (HBS + 6 or so), in which he’s incredulous that Jesús intends to marry Laura, and says “Don’t come running to my couch when the going gets too rough!” Jesús’s reply: “Don’t worry! I’d head for the hills first!”

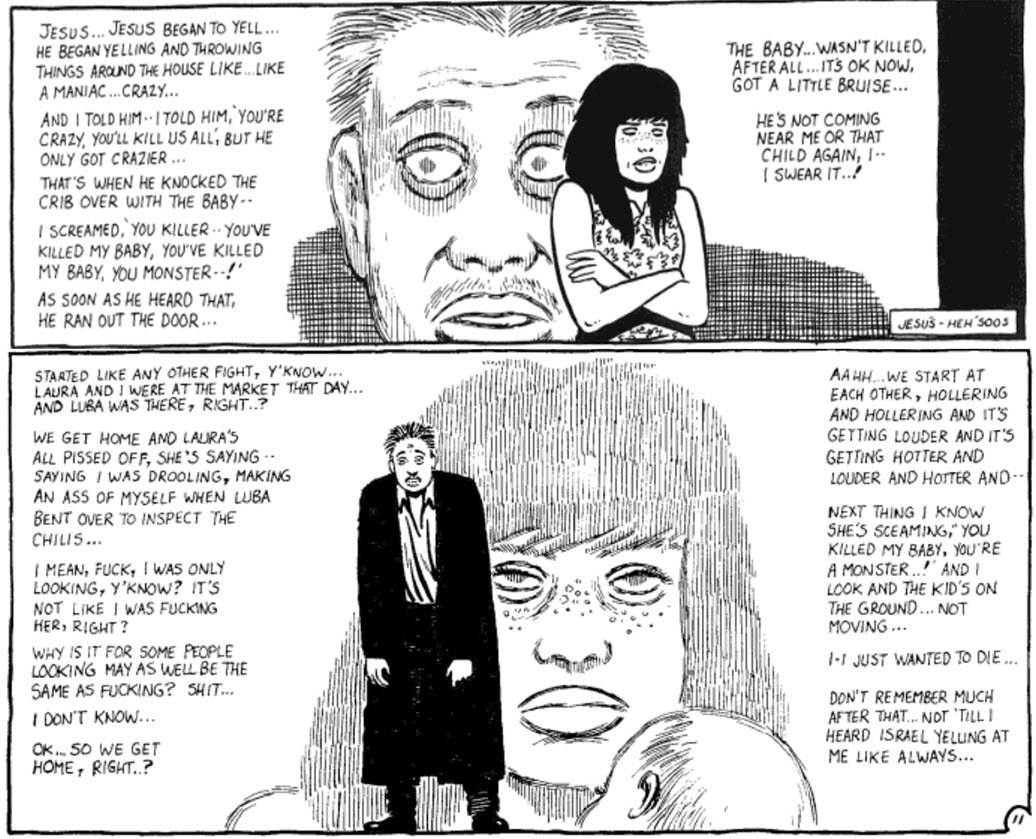

Coming out of the flashback, Israel screams at those hills in rage and frustration, and to his surprise, Jesús replies. The men find him, and in one last trip to the (very recent) past, Jesús tells the story of how his fight with Laura happened. I would make the case for this as another flashback, though it is narrated rather than drawn — it’s just one wide panel with columns of text on either side, and an image in the center of Jesús, superimposed over an extreme close-up of Laura and their baby, drawn fainter to indicate a presence in memory, not reality. This panel echoes the one that opens this half of the story, in which Laura tells her version of their conflict, with a ghostly close-up Jesús behind her. Jesús reveals that their argument was about his sexualized gazes at Luba, for which all the previous flashbacks set the stage.

Thus does Gilbert not only illustrate a character through others’ experiences of him, he also defines the community closest to that character, all while setting up and resolving a mystery quest plot. In “Absent Friends”, Chapter 2 of Watchmen, Alan Moore doesn’t resolve the mystery of Blake’s death, but he does use the very same device to show us exactly who The Comedian is, as his closest community saw him. Again, the flashbacks are from five different characters, moving forward in time. (I’ll use W to denote the main story timeline (1985) in Watchmen as a baseline, similar to HBS above.)

Sally Jupiter starts the flashbacks, remembering back to the time of The Minutemen (W – 45 years) and Blake’s attempted sexual assault of her. The next three flashbacks take place at the funeral: Adrian recalls the Crimebusters meeting in 1966 (W – 19 years), Jon VVN night in 1971 (W – 14 years), and Dan the police strike riots of 1977 (W – 8 years). Finally, after the funeral, Rorschach wrings out one last flashback, this one from Moloch remembering The Comedian’s “last performance” (W – a few weeks.)

Just as each of the “Laughing Sun” flashbacks helped paint a portrait of Jesús as oversexed and fixated on Luba, so do the flashbacks in “Absent Friends” center around a theme: The Comedian as a vile man who nevertheless understands many things that others don’t. The vileness is clear — in the space of a few pages, but spanning decades, we see him (nearly) raping Sally Jupiter, murdering a Vietnamese woman pregnant with his baby, and tear-gassing civilians. The other two flashbacks show his knowledge — he sees through Captain Metropolis’s motives in the Crimebusters meeting, and cryptically tells Moloch of the island he’s discovered, in the process alerting Veidt that Blake knows too much. Even in the flashbacks that demonstrate his detestable nature, we also see his insight, such as when he identifies Hooded Justice’s fetish, or tells Dr. Manhattan, “You don’t really give a damn about human beings.”

Just as with Jesús, Blake and his story come into focus through the eyes of the community that surrounds him. The reverse is also true — we learn the nature of the community as demonstrated through its interactions with the central character. In “The Laughing Sun”, the character of that community is cohesive, and that cohesion is crucial to its success — Heraclio is able to speak to the mountain Indians, Isreal is capable of provoking Jesús out of silence, and Satch knows just what to say to make Jesús receptive to being brought home. The flashbacks, too, are mostly of bonding moments between the boys — even the conflict between Israel and Jesús carries a clear loving undertone.

In Watchmen, by contrast, the community is fragmented — split by differences in distance, differences in viewpoint. Their flashbacks to The Comedian demonstrate their distance from him too, every one of them injured or puzzled by his actions. In fact, two of those flashbacks (Moloch’s and Adrian’s) are at the heart of the story’s main plot, which serves to drive all the characters apart, only to bring them back together at the end under a heavy layer of irony, tragedy, and fragility. The only one of the main characters to opt out of that final community is Rorschach, just as he is the only one in this chapter who doesn’t get a flashback.

How to Travel Through Time

The stacking flashbacks device is powerful, but it’s also worth a look at how the mechanics of it are executed. “The Laughing Sun” uses two different techniques. The more minor one I’ve already mentioned — a long panel with columns of text on either side of the storyteller, and a fainter image of the story’s subject looming up hugely behind. I see these as flashbacks, but what’s true is that they’re only narrated through illustrated prose, not sequential art like the others, so they have very little disruptive impact on the main story timeline.

The other flashbacks in “The Laughing Sun” all start as thought bubbles4, but with an image inside rather than words. The first of these, Vicente’s, calls attention to itself because the previous panel showed Vicente with a traditional thought bubble that does contain words. Then, within the flashback, each of the panels has scalloped corners rather than hard right angles. The end of Vicente’s flashback highlights the device in a different way, as a thought bubble above Vicente’s head shows himself and Jesús as boys, who themselves have a thought bubble over their heads, with an image of the devil chasing them through Hell. The bottom of this panel has right-angled corners, while the top corners are scalloped. The other three flashbacks follow a similar pattern — thought bubble with an image (and sometimes a word balloon inside the thought bubble), scalloped corners on the memory panels or portions.

Gilbert first used these two approaches — narration over static images and images inside thought bubbles — in “Act Of Contrition.” The next Palomar story after “The Laughing Sun” to contain a flashback was “The Reticent Heart,” which actually announced it with a caption reading “Flashback: A few years before Carmen and Heraclio became wife and husband,” and then later signaled “Flashback within the flashback: Years ago, on a warm, late afternoon in Palomar…” In a 2008 interview, Gilbert revealed his struggles with the device:

I ran into trouble with that a lot. When I first started, I used the old comic-book cliché of writing the word “flashback” just to make it clear for the reader. As my editor suggested, the strip was starting to develop in such a way that it didn’t really need this nudge. So I started presenting a flashback more like in a film. But I wasn’t so good at it. What I thought was a natural, smooth transition from modern times to a flashback wasn’t always identifiable by the reader. In a lot of reprints, I rework transitions to make a flashback clearer. (Your Brain On Latino Comics, pg. 176)5

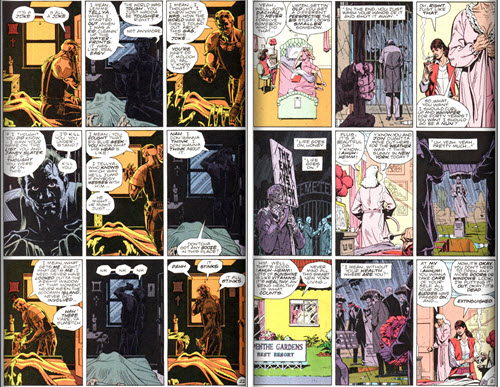

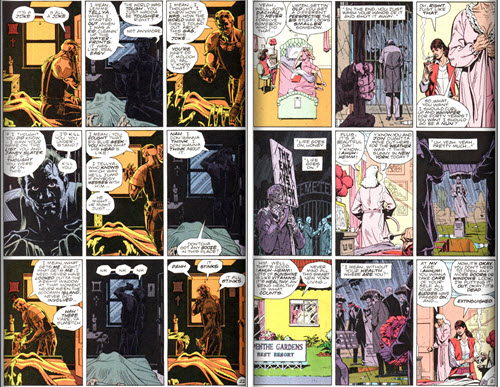

In Chapter 2 of Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons show their mastery of those transitions. The chapter relies upon a few different techniques to signal that a flashback is beginning or ending, and by far the most prominent one of these is image-matching. The first flashback of the chapter starts with a bright glare off the Minutemen’s picture, followed by a panel of the camera flashing, and then a panel of the Minutemen posing for that picture, which begins the narration in earnest. Similarly, a panel of Adrian’s impassive face at the funeral precedes a panel of him masked as Ozymandias, in the same exact pose, to begin the Crimebusters meeting flashback. The Crimebusters flashback goes out through the same door, transitioning from a panel of Adrian masked in 1966 to one of him unmasked in 1985. Clever match cuts abound, such as when we go from The Comedian gripping Moloch’s lapels as Blake tells his story to Rorschach gripping Moloch’s lapels as Moloch recounts it.

Where matching isn’t in place, irony often is, such as in the cut from Sally having just been sexually victimized to the Tijuana bible image of her saying lustily, “Oh! Treat me rough, sugar.” The only transition that approaches a traditional comics technique is the one leading into Moloch’s flashback — captions of Moloch beginning to tell the story overlay an image of The Comedian sitting on Moloch’s bed, not so different from how Gilbert handles Archie and Luba’s flashbacks in “Act Of Contrition.” That’s as far as the connection goes, though — there are no thought bubbles in Watchmen, and certainly no captions reading “Flashback.”

That said, Gilbert made rapid strides in his technique during the two years that separate “The Laughing Sun” from “Absent Friends.” “Holidays In The Sun” (cover-dated January 1986) is a story of Jesús in jail, in which panel transitions slip seamlessly between fantasy and reality with no artificial bracketing. Even within his dreams, Luba’s face changes abruptly to Laura’s via panel transition. By the time of “Duck Feet” (June 1986) and “Bullnecks And Bracelets” (January 1987), flashbacks in Gilbert’s stories begin and end with no announcement whatsoever of the time-shift, sometimes jumping across years in the space of a few wordless panels.

During roughly the same period, there are flashbacks aplenty over on the Jaime side of L&R as well. “The Secrets Of Life And Death Vol. 5” (January 1987) is mostly flashback, with a transition accomplished by a scallop-sided panel overlaying one set in the present. The panels within the flashback look normal (straight corners), except for the one coming out of the flashback, which has one scalloped corner. Then in “The Return Of Ray D.” (April 1987), Jaime accomplishes a transition to the past using the same image-matching technique as “Absent Friends” — three characters in similar poses, but dressed differently (and one transforming from a background figure into a major character in the flashback), with no other mechanical conventions overdetermining the shift.

It’s not impossible that technical influence was flowing both directions between Los Bros and Moore/Gibbons. Certainly as Love And Rockets progressed, their time-shifting grew bolder and bolder, extending to dizzying extremes in stories like Gilbert’s early-90s “Poison River”, which would sometimes rapidly crosscut between years or decades, jumping timelines from one panel to the next without explanation and leaving the reader to piece it together. Even the opening pages of its chapters showed characters at various points in their timelines.

At the very least, it seems fair to say that both Love & Rockets and Watchmen are exemplars of an era in which formal experimentation in comics flourished. They were far from the first to use flashbacks — Harvey Kurtzman in particular, among his many 1950s achievements, used flashbacks to powerful effect in stories like Big “If”.6 Nor were match cuts a new thing — Stanley Kubrick among many others made masterful use of the technique in film. But 1980s comics like Watchmen and L&R brought these sophisticated techniques together repeatedly and consistently, for a wide variety of precisely controlled narrative effects, and thereby pushed the boundaries of comics, leading to a rich artistic payoff for a large number of works, a general expansion of the form’s visual vocabulary, and the increasing sophistication of its audience.

Beyond The Gutters

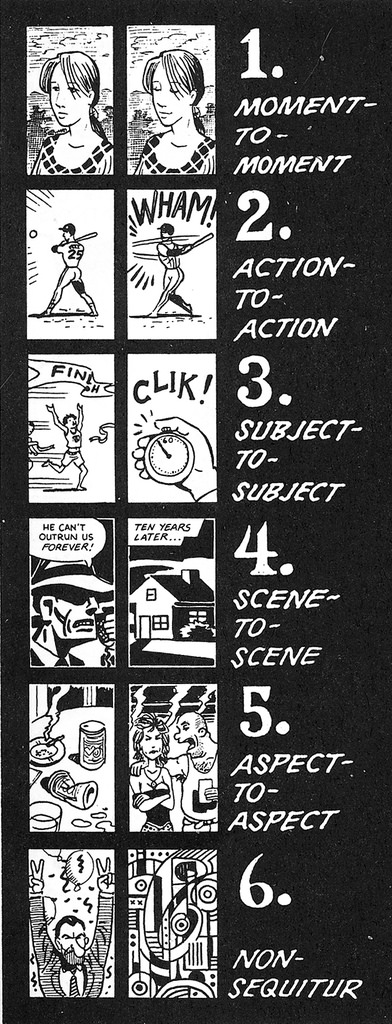

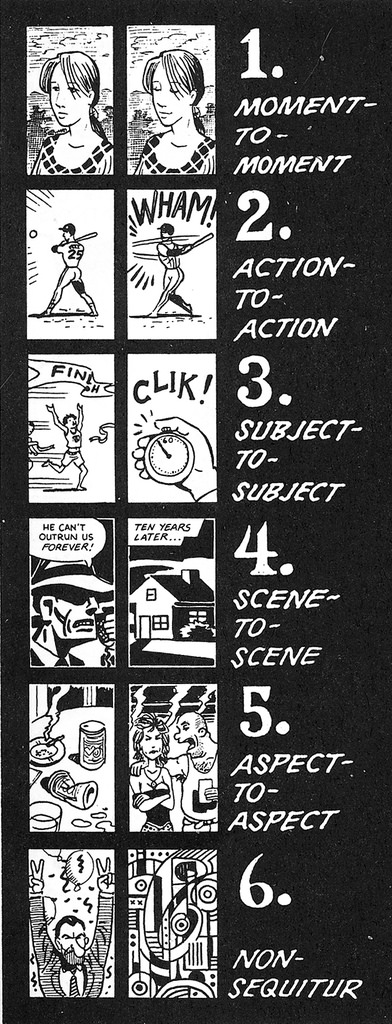

In his landmark 1993 study Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud breaks down a few different ways panels can relate to each other:

- Moment-to-moment: Panel A depicts the moment before Panel B, with a few seconds at most elapsing between them.

- Action-to-action: Panel A depicts the action before Panel B, even if there’s a bit of time separation between them — for example pouring a drink, then drinking it.

- Subject-to-subject: Panel A depicts one part of a scene, and Panel B depicts a different part, moving time forward as well.

- Scene-to-scene: Panel A and Panel B are separated by some significant distance in time or space, or both.

- Aspect-to-aspect: Panels A and B depict different aspects of “a place, idea, or mood.” There is very little sense of time passing between these panels, which is what separates them from subject-to-subject transitions.

- Non-sequitur: Panels A and B seemingly have no relation to each other.

As McCloud explains it, the space between panels is known as the “gutter”, and the imaginative connection performed by the reader across this gutter, in order to accomplish these transitions, is “closure.” His observation rests upon the fact that comics are sequential, and that the connections between the images in that sequence must be made by the reader.

Rocco Versaci, in This Book Contains Graphic Language, takes this line of reasoning a little further, noticing the ways in which comics can be both simultaneous and sequential: “[U]nlike film, which unspools at a more or less predetermined (and from the viewer’s perspective, uncontrollable) pace, comics creators can play with the design of an entire page by manipulating the visuals within panels and the panels themselves within the page to create additional layers of meaning. Thus, a comic, in addition to unfolding temporally, also exists ‘all at once,’ and this existence is a feature unique to the medium.” (pg. 16)

Watchmen frequently capitalizes upon this “all at once” quality of the page. For example, in Moloch’s flashback, there’s a flashing light outside his window, which alternates between illuminating The Comedian and leaving him in darkness. The panels in the 3×3 grid thus alternate between oranges and blues, as moment-to-moment transitions in The Comedian’s speech. The result is a bright X across the page, complemented by a dark O. This rhythmic alternation also appears in the first few pages of the chapter, this time in scene-to-scene transitions, as rapid cuts between California and New York create these interlocking panel patterns of brightness and darkness.

What’s at play here is the tension between images all at once, and images in sequence — we see the page all at once, even as the panels are sequential. Hatfield views Los Bros as masters of manipulating this tension: “Gilbert and Jaime freely manipulate time, space, and point of view, collapsing hours or even years into abrupt transitions, splicing together reality and fantasy, and discerning patterns in widely separated events. Relying on the cohesiveness of the total page (and the familiarity of L&R as a series) to guide and reassure their readers, Los Bros pushed the tension between single image and image-in-series to the extreme, transitioning from one element to the next without warning.” (pg. 70)

With his reference to “the familiarity of L&R as a series”, Hatfield gestures to yet another level of tension in comics, in which any of McCloud’s transitions can occur: the tension between single episode and episode-in-series. Because comics stories are so frequently serialized, readers are called upon to perform closure between episodes. Many Marvel comics, for instance, are pieces of a continuing story, and thus have a tendency toward moment-to-moment transitions between episodes — issue #191 is likely to pick up right where #190 left off, at least if #190 ended on a cliffhanger. If one issue wraps up a story, the next issue is likely to pick up on a time not too much later in the title character’s life — a scene-to-scene transition.

Closure between episodes is the connective tissue that holds comic book sagas and universes together. Those connections, taken in totality, form that beloved shibboleth of comics aficionados: continuity. Continuity is our overall experience of a story, as strung out over multiple episodes. Just as certain artistic effects are only possible on a total page, so too can continuity empower dramatic moments, or amplify dramatic blunders. When the Green Goblin killed Gwen Stacy in The Amazing Spider-Man #121, it was continuity that made the moment so powerful — readers had known Gwen for eight years at that point, over 90 connected issues. She was a part of readers’ lives just as she was a part of Spider-Man’s life. That is a level of intimacy impossible to achieve within the boundaries of a single book. Similarly, when the “Clone Saga” attempted to assert that the last twenty years of Spider-Man stories hadn’t really been about Peter Parker, it was continuity that led fans to their pitchforks and torches.

Both Gilbert Hernandez and Alan Moore use continuity to their advantage. The time-jumps that happen after “Heartbreak Soup” challenge closure, requiring the reader to figure out where the story occurs in relation to that first baseline. By the time of “The Laughing Sun”, Gilbert seems to have settled more or less into the HBS + 10 zone, but it’s clear that our perspective can come unmoored in time at any moment. By the same token, part of what gives “The Laughing Sun” (among many other Palomar stories) its power is the fact that we know these characters from many positions in time, which enriches and deepens our understanding of their relationships to themselves and each other. Unlike with Spider-Man, though, we do not travel through time alongside them, but rather begin to see their stories from multiple angles at once. Analogous to a comics page, Palomar exists “all at once” for us, increasingly so as continuity builds.

Watchmen is a self-contained story, not an ongoing saga, but still, it was serialized over 12 issues, and Moore certainly uses the continuity of that year-long publication period for dramatic effects. Clearly, the clock that ticks down at the end of each chapter is powered by closure — we know where that clock has been, and our knowledge of the number of issues in the series lets us know where it’s going. Similarly, even as early as Chapter 2, Gibbons draws panels that call back exactly to previous episodes in the series, relying on our knowledge of those episodes to provide the full meaning of the recontextualization. Even the end papers occasionally employ continuity, with part II of Under The Hood ending in Chapter 1, and part III picking up immediately in Chapter 2.

For Watchmen, and to a lesser extent for Love And Rockets, there is an additional level of tension beyond this: the tension between genre instance or invocation and the broad genre as a whole. Watchmen places itself in the superhero genre, as it existed in 1986, and is ready for its readers to come in with certain expectations of how that genre works, its conventions and status quo. Moore takes advantage of this level of reader knowledge to produce surprise, shock, and dismay as his characters and situations contrast with what’s expected, as well as to introduce overtones that call the rest of the genre into question. Love And Rockets, on the other hand, begins within expected comics genres of science fiction and fantasy, then moves quite deliberately outside them, landing in a place that defines its independence partly in opposition to what’s on offer in the rest of the comics mainstream.

Even beyond genre, there is yet one more layered experience available from these books: the experience of multiple readings. Critic Douglas Wolk notices this level in Jaime’s work: “The subtleties of his characters’ interactions really only appear on re-reading… despite the technique Hernandez has picked up from his brother of jump-cuts within each scene, it reads so smoothly that you have to make a conscious effort to slow down and note what else is happening.” (Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work And What They Mean, pg. 200) The same points apply to Gilbert’s work as well.

This is very similar to my experience of reading Watchmen. When I first read it, in the mid-90s, I found it enjoyable but unremarkable, and was surprised that it was praised so highly. That time, I was reading for plot, not really noticing structure, and was coming to it from the context of having already encountered many of its imitators, and daring it to live up to the aura of praise that surrounded it. Then, when the movie came out, the press around that event helped me to realize I’d missed a number of layers in that first reading, encouraging me to give the novel a second look. The result is this project. Re-reading (and re-reading, and re-reading) Watchmen has led me to a far deeper appreciation of the book than I had after that first time through, and the same has been true as I’ve reread Palomar stories in preparation for this post.

What God Feels Like

Images, pages, episodes, genres, iterations of reading. All of these contribute to an experience of time connected with a particular work. Past each of these sequences, there is a sense of totality as well, and if you’re not thinking of Dr. Manhattan by now, you probably need to re-read Watchmen. William Kuskin observes a couple of these layers in a 2010 article: “In that he sees time as an object, Dr. Manhattan’s perspective is similar to the reader’s, who can perceive the whole page at one glance and the entire narrative in one turn through the book.” (“Vulgar Metaphysicians: William S. Burroughs, Alan Moore, Art Spiegelman, and the Medium Of The Book”, in Intermediality and Storytelling, pg. 54)

I remember once talking to my friend Trish about a television show I was watching. She had already seen it; I was catching up on DVD. She asked me where I was in the sequence of episodes, I told her, and she remarked, “This must be what God feels like.” She knew what was going to happen to all the characters, and by extension what was going to happen to me. She saw the entire series in total, where I was currently still living through it in sequence — she looked at me from outside time, knowing I was trapped inside it but would transcend it to join her soon.

Time is a strong motif within Watchmen, starting with the title. Watchmen carries the sense of “guardians”, as in “watchmen on the walls of the world’s freedom,” but the character most connected with time is also the son of a watchmaker, who aspired to become one himself. Their predecessors were the Minutemen, a name linked with the American Revolution but linked also with brevity, and fragmentation of a temporal whole. The watchmaker’s son becomes unmoored in time, seeing it as “an intricately structured jewel that humans insist on viewing one edge at a time, when the whole design is visible in every facet.” I’m still not completely convinced by Dr. Manhattan’s point of view, perhaps because he combines simultaneity and sequence in a way I still don’t understand, despite having looked at many a comics page and then read the panels. For me, the whole design of jewel that is Watchmen was only visible upon re-reading, but that jewel continues to reveal more of itself, the longer I look.

So too are we unmoored in time when reading Gilbert Hernandez’s Palomar stories. What is sequential for us is not so for the characters — we see them as teens, then suddenly adults, then flashing back to various points in their histories. Their existence in all these timelines is simultaneous for us, experienced sequentially (though out of chronology) but existing side by side at the same time. Gilbert, like Moore, exploits our sequential experience of reading to break apart the sequential time in his world.

Thus, as readers of Love and Rockets, we ascend almost to the godlike status of Dr. Manhattan. We don’t see the whole jewel in advance, and in fact, we don’t ever see the whole jewel at all, but we see enough facets to at least comprehend the concept of the whole. The same is true of Watchmen to an extent — indeed, the same is true of any book to an extent, because we understand the whole after reading, even if we choose to revisit the parts. But what’s special about Love And Rockets, at a level unmatched by Watchmen, is its powerful combination of continuity and nonlinearity — we can spend years and years with these characters, but their years are not ours, because we know so much of their future, so much of their past.

We learn those things not in the traditional way, following a timeline, but rather from above, via synecdoche, seeing the parts that imply the whole. Just as we assemble a picture of Jesús from the memories of his friends, just as we create Blake from our knowledge of who he has been over time, so too do we create the worlds of Palomar and Watchmen by seeing enough facets to understand the jewel. For us as readers, the world of the story (in all four of its dimensions) is our absent friend, who becomes present through our accumulated knowledge.

Next Entry: The Last To Know Who’s Fooling Who

Previous Entry: Comin’ For To Carry Me Home

Endnotes

1The convention I would normally follow for citing an author’s name is to use last name, such as I do with Moore and Gibbons. However, since I’ll be referring to both Hernandez brothers, I’m defaulting to using their first names as the least unwieldy alternative. No disrespect is intended. 🙂 [Back to post]

2The chronology on these two pieces is a bit mystifying to me. They’re reprinted in the Heartbreak Soup collection published by Fantagraphics in 2007, which touts its contents as “assembled for the first time in perfect chronological order.” They show up between “Heartbreak Soup” (1983) and “Act Of Contrition” (1984) in that volume. However, “A Little Story” is dated 1985 (it apparently debuted in the first L&R trade paperback), and “Toco” is dated 2002. Why Fantagraphics considers this “perfect chronological order” is quite beyond me. In any case, I’m leaving this paragraph in as a description of my own Palomar reading experience, which happened in the reprint, but note that for readers of the original magazine (including Moore), Palomar stories jumped from “Heartbreak Soup” straight to “Act Of Contrition.” [Back to post]

3Tipped hat and deep bow to Charles Hatfield for the detective work to match these dates.[Back to post]

4Thought bubbles have fallen out of favor over time in some modern comics, replaced by superimposed captions, images, or sudden panel transitions. Watchmen is a prime example of the no-thought-bubble approach.[Back to post]

5Gilbert’s last remark brings up a problem with the sort of critical comparative work I’m doing here — I’m working from reprints of Love And Rockets, as I don’t have access to the original issues. So if Los Bros changed things for the trade paperbacks, it’s quite possible that some of the mechanics I’m discussing may not have been as Moore saw them. This is an unfortunate consequence of the disposable and ephemeral nature of original comics pamphlets, which can sometimes be recovered via digital (albeit usually illegal) means, but are otherwise locked behind barriers of expense or distance. If you’ve got original L&R issues and can shed light on discrepancies between them and the collections, by all means let me know in the comments! [Back to post]

6Another bow to Charles Hatfield for drawing this line.[Back to post]