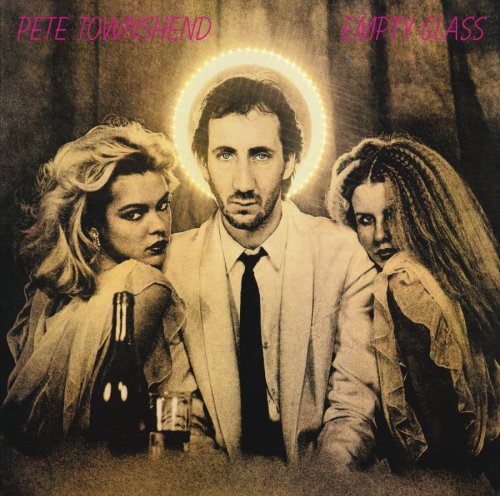

There are lots of reasons people make solo albums. Sometimes it signals the next phase of an artist’s career after their band’s final creative demise, as with Sting, or Paul McCartney, or Paul Simon. Some artists produce far more material than their band can accommodate, such as Stevie Nicks, or Amy Ray, or Phil Collins. Sometimes they’re really just side projects — Stephin Merritt, Thom Yorke, and Mick Fleetwood come to mind. But some solo albums demand to be made, and such was the case with Pete Townshend’s Empty Glass.

Townshend had been writing for The Who since 1964, a songwriting career of relentless innovation and spectacular success. But by 1980, that career and indeed his whole life was foundering on a variety of shoals and reefs. He was struggling with a substance abuse habit, including alcohol and heroin. His 12-year marriage was coming apart. Punk rock had exploded in Britain, creating a culture that cast Townshend and The Who in the uncomfortable role of Establishment dinosaurs. The last Who album, Who Are You, had been a commercial success but was difficult to record, and had received mixed reviews. During the Who Are You tour, 11 fans died in a crowd crush due to festival seating arrangements in Cincinnati. And Keith Moon was dead, claimed by an overdose on the sedative he’d been prescribed for his alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

The songs on Empty Glass give us a look into Townshend’s anguish over these issues, sometimes obliquely and sometimes with startling directness. But even more than that, they show an artist freed from a musical framework that had come to constrict him more and more over the years. The Who is a phenomenal band, obviously, and for many years they had served as Townshend’s creative outlet, but The Who has its limitations. Chief among these is Roger Daltrey as a frontman, and I say that with full respect to Daltrey’s sensational stage presence and potent singing voice. Daltrey is many things, but one thing he isn’t is uncertain – he has a clear “golden god” image, and extends that image to the band in general with swagger and machismo.

But Townshend’s new songs, though some of them were firmly in the Who idiom on a musical level, were not necessarily a good match with Daltrey. The album’s opening track “Rough Boys” is a perfect example. Musically, it could easily be a Who song. Lyrically, it starts out that way too: “Tough boys / Running the streets”. That’s an image that would have been at home on Quadrophenia or Who’s Next. But the song quickly takes an unexpected turn — “Rough toys / Under the sheets”. Okay, so now we’re talking about rough sex, but even that’s not so beyond the pale. Here’s what’s next, though: “Rough boys / Don’t walk away / I very nearly missed you / Tough boys / Come over here / I wanna bite and kiss you”.

Whoa! So, hey, it turns out maybe the rough sex is with the boys themselves! And the homoerotic tone gets clearer and clearer: “I wanna see what I can find”… “Gonna get inside you”… “I wanna buy you leather”… “We can’t be seen together”. And just in case that’s not transparent enough, Townshend also gives us “And I Moved,” an unmistakable portrait of a tender erotic encounter with a man, whose “hands felt like ice exciting / As he laid me back just like an empty dress.”

Now is probably a good time to say that yes, of course, Pete’s not necessarily writing about himself, and in fact is more prone to write in character than most rock songwriters. And yes, it’s true that “And I Moved” was originally written for Bette Midler, though that doesn’t change the fact that he still chose to sing it himself, without changing the gender. In any case, can we really picture Daltrey singing these songs, at least in the way they’re presented here? It was daring enough in 1980 for Townshend to put them forward, and what they express was not in the Who’s iconic vocabulary, at least not at that time.

Empty Glass is full of one thing, and that is multiplicity, more than The Who could have contained. Nowhere is that clearer than on the astonishing “I Am An Animal.” Most of the song is sung in Pete’s “sweet” register — think the “don’t cry” bridge from “Baba O’Riley”. Townshend’s voice is very different from Daltrey’s, but for me it has a magic all its own, tough and tender at the same time. Parts of the song are sung almost in a hush, like a lone choirboy practicing in a cathedral.

The words put forth a series of bold, contradictory metaphors: “I am an animal / My teeth are sharp and my mouth is full”… “I am a vegetable / I get my body badly pulled.” “I am a human being / And I don’t believe all the things I’m seeing”… “I am an angel / I booked in here, I came straight from hell.” In one moment, he’s proclaiming himself “queen of the fucking universe”, and almost immediately afterwards, “I am a nothing king.”

It all returns to the chorus, in which the speaker is lost in a timeless present moment, without history or future, where he’s being carried along into the unknown, accompanied by all these versions of himself:

I’m looking back

And I can’t see the past anymore, so hazy

I’m on a track and I’m traveling so fast

Oh for sure, I’m crazy

According to Townshend, the song “Empty Glass” is based on 14th century Sufi poem, in which the heart is an empty cup filled up with God’s love. And that certainly fits the words, but I would suggest that in another sense, the empty glass of this album is Townshend himself, so long a vehicle through which another voice expressed itself. When he stepped out of that structure, he found himself filled with beautiful multitudes, some complementary, some oppositional.

He is lost, yes, and desperately seeking — “I’m losing my way”… “I’m boozing to pray”. Some lines seem to speak clearly to his troubled relationship — “I don’t know what I have anymore / Anymore than you do”… “I don’t know where you are anymore / I’ve got no clue.” As another great songwriter once put it, pain is all around.

But at the same time, love is all around too. Empty Glass contains two of the greatest love songs Townshend ever wrote: “Let My Love Open The Door” and “A Little Is Enough.” Both of them are open-ended enough to encompass many kinds of love — romantic, agape, divine. Both have a spiritual component, reaching toward a kind of devotion that is generous, open, and focused outward. And both are musically ecstatic, locating an elevated bliss in the declaration of passionate attachment.

Pain and love sit side by side most manifestly in “Jools and Jim”. Fundamentally, this is a furious song, striking out vehemently at a poison pen of the British press named Julie Burchill, who had recently co-written a book-length rant about rock and punk called The Boy Looked At Johnny with her future husband Tony Parsons. In a promotional interview for their book, they had slagged off Keith Moon, saying “we’re better off without him.” Townshend lets them have it with both barrels, spitting out line after line of rebuke: “Typewriter bangers on / You’re all just hangers-on”… “You listen to love with your intellect”… “Your hearts are melting in pools of gin”… “Morality ain’t measured in a room he wrecked.”… “They have a standard of perfection there / That you and me can never share”.

But in a remarkable bridge, Townshend admits his own complicity, and allows for the possibility of connection even with such enemies:

But I know for sure if we met up eye to eye

A little wine would bring us closer, you and I

Cause you’re right, hypocrisy will be the death of me

And there’s an I before e when you’re spelling ecstasy

And you, you too…

Immediately afterward, he invokes Krishna, and says it was “for you that Jesus’ blood was shed.” He finds forgiveness in his heart even for those who have stabbed it. He doesn’t let them off the hook — the “you too” attaches to the statement about hypocrisy in my reading — but he believes “for sure” that they could connect if they met on a human level. We don’t see this sort of stance taken very often in rock and roll, do we? Townshend blends rebellion and humility, anger and contrition into something more potent than either.

It’s clear that in part, Empty Glass was a reaction to punk rock. He dedicates “Rough Boys” to both his children and to the Sex Pistols. “I am an animal” not only echoes the Pistols’ “I am an antichrist / I am an anarchist”, it replies back to their song “Bodies”, in which the chorus cries, “I’m not an animal!” But where punk culminates in blistering anger, for Townshend that’s merely a starting point, on a road that ends in an open door.