Hi all. As I’ve mentioned, the Album Assignments series derives from a biweekly-ish game in which my friend Robby and I trade off assigning an album to each other. I’ve been writing about the experience, and from time to time so has Robby. With his permission, I’d like to share with you his lengthy and imaginative take on The Art Of McCartney. His writing style is pretty different from mine, and sometimes his opinions are too, but I really enjoyed this cross-disciplinary journey through music and visual arts. I hope you do as well. Take it away, Robby!

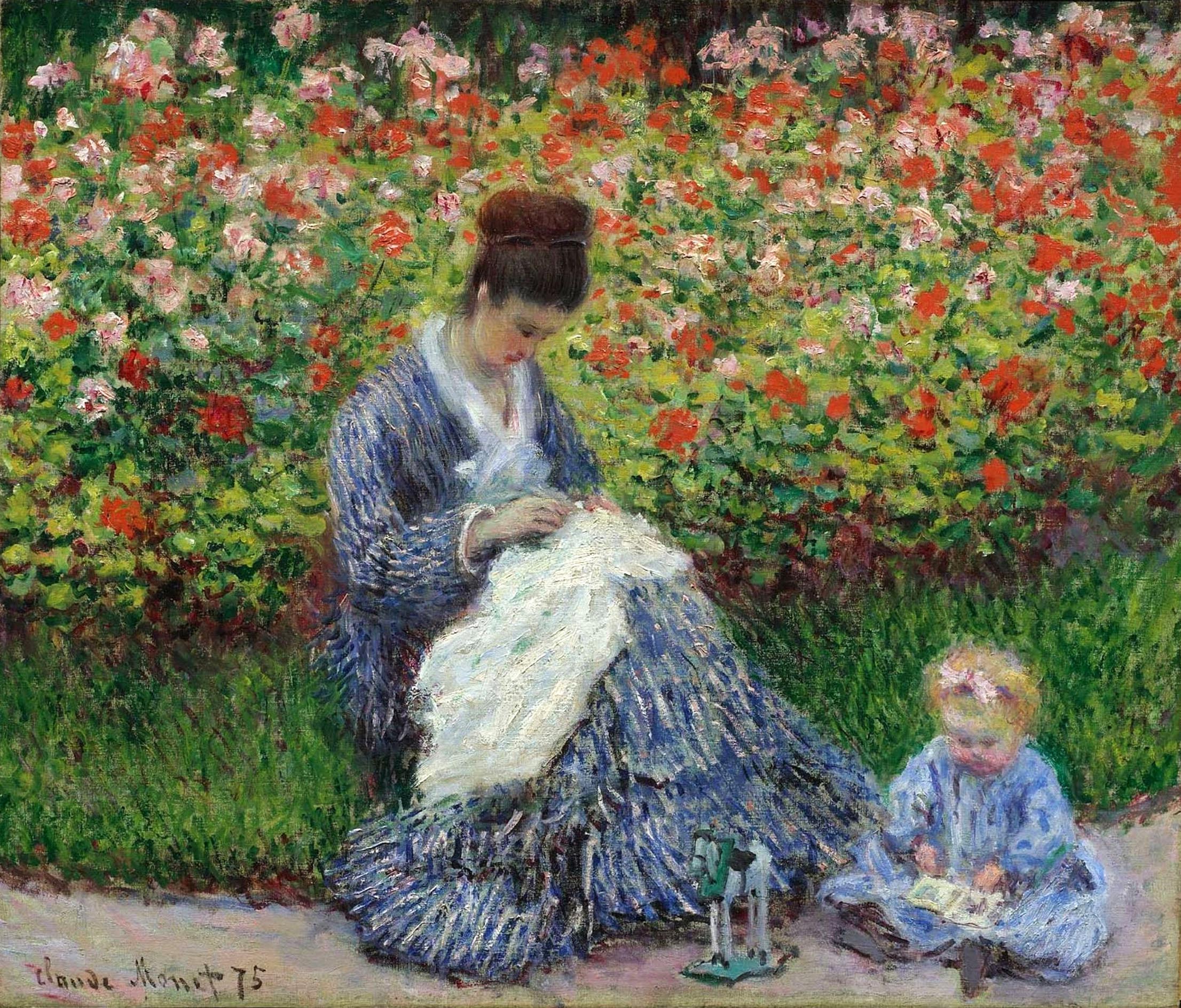

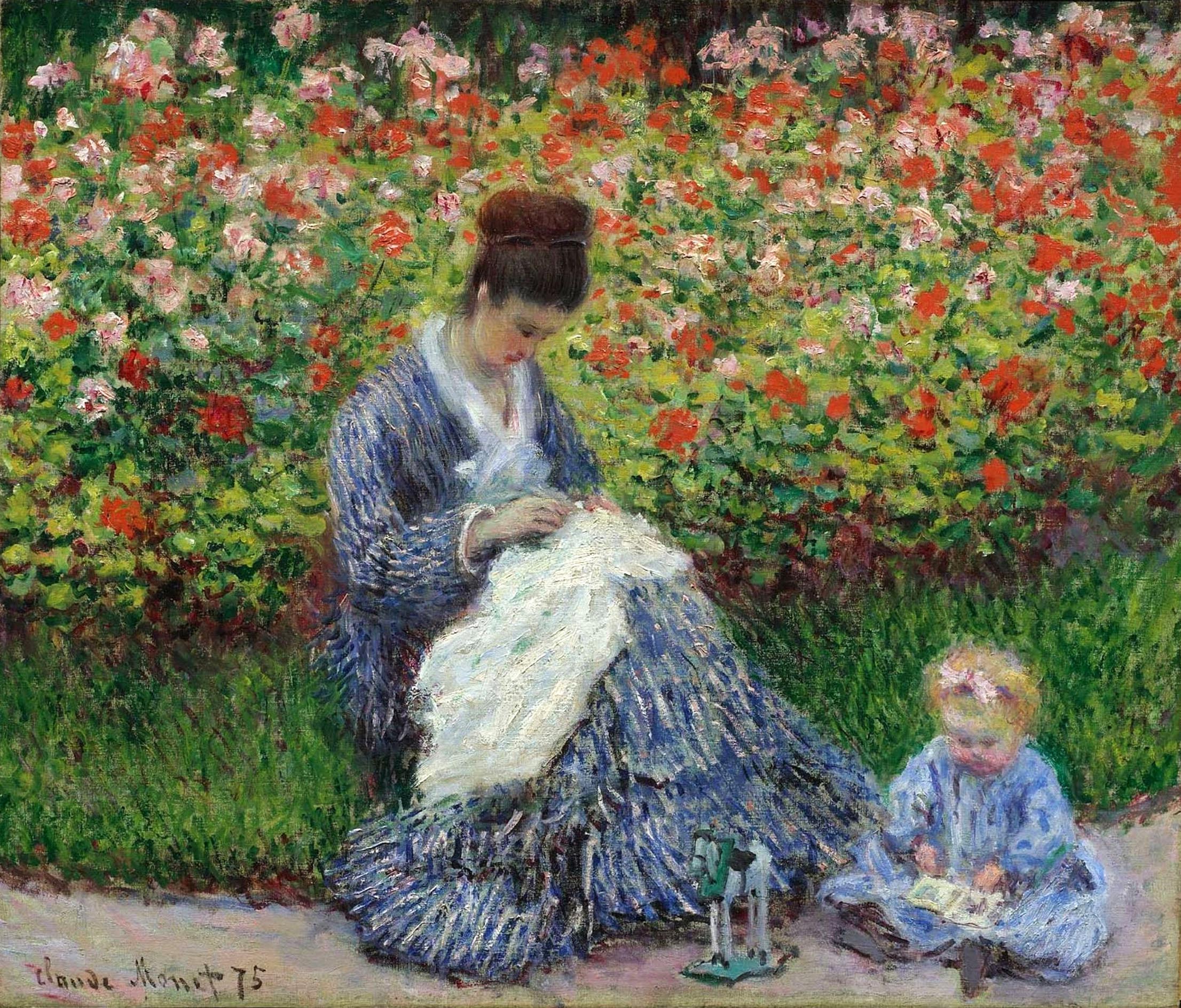

Claude Monet – Madame Monet And Child (1875)

The Art of McCartney is a perfect title for this Paul McCartney tribute album, an album that has an all-star lineup of artists, new and old. It got me thinking as I began listening to it that each musical artist on the album is also like a visual artist, as they contributed their own unique artistic style to these classic works of McCartney. They offered their brush strokes and paints to their own canvasses, painting McCartney from their own perspectives.

For me, this album symbolizes world famous artists getting together and repainting Monet paintings from their own points of view. McCartney is the Claude Monet of the rock and roll world. His combination of lyrics and music are unmatched, and as years go on his music takes on whole new meanings. Like Monet, if you stand too close, you are not sure about what you see but as you back up and get perspective, those images become more vivid and beautiful. Monet is the master and Paul McCartney is the master. Images of paintings and artworks began to flood my brain as I listened to this tribute album to Monet/McCartney. Here are the artists and the McCartney pictures they painted.

Billy Joel – Maybe I’m Amazed/Live and Let Die

Billy Joel is Paul Gaugin, as he gracefully paints McCartney’s heartfelt lyrics with conviction and respect. Gaugin was a passionate painter who paid very close attention to detail, and Joel is no different with these two classic McCartney songs. “Maybe I’m Amazed” is a song that portrays deep devotion for a love that he can’t believe he has. Joel paints this song with much respect to the original, and conveys that meaning with the detail that only Gaugin can bring to his paintings. “Live and Let Die” allows Joel to unleash his emotions a bit, but still in a respectful, detailed way that doesn’t veer from McCartney too much. It works here, and like with any Paul Gaugin painting, I am mesmerized by the beauty and seemingly effortless brush strokes that expose so much meaning.

Bob Dylan – Things We Said Today

Bob Dylan. I could write for days and days about Bob Dylan and the impact he has made on American music. Dylan is Picasso on this classic Beatles song. He is a master painting another master, with his rough voice and fast-paced tempo. Dylan adds importance to this McCartney-penned song, and I felt like I was witnessing something very special and intimate, listening to Picasso paint Monet. Like Picasso, Dylan experimented with many different genres and styles in his life. I pictured Picasso-Dylan painting Monet landscapes in his cubist style throughout “Things We Said Today” and the result was one legend lending his devotion to another legend.

Heart – Band on the Run/Letting Go

Mary Cassatt was a pioneer in the male-dominated art world. She found her own unique voice and talent, painting private moments of women and their children in France. She captivated people and created an intimate relationship with her subjects and her admirers. Heart is Mary Cassatt in “Band on the Run.” They capture the intimate feel that song has when they sing, “but we never will be found.” The Wilsons were pioneers in the music industry, and they have always done things their own way, creating their own place in rock history. They paint both these McCartney paintings with precision and clarity, and make them their own. “Letting Go” is like what Cassatt would have done with “Madame Monet and Child,” to turn it into “In the Garden”. Heart took that intimate Monet painting and turned it into their own intimate portrait, but still honing the original master’s work. They are amazing, how they can cut to the chase with their aggressive lyrics and straight-ahead style. A bittersweet song about wanting to move on but holding onto the past is captured masterfully, like only Cassatt can paint and only the Wilsons can perform.

Steve Miller – Junior’s Farm/Hey Jude

I was struck how good Steve Miller sounds now. His clean, crisp vocals sound like he just came from the same session where he recorded his 1977 classic Fly Like an Eagle album. Miller conjures up clear images for me, as he reveals and unwraps the lyrics on “Hey Jude” like a Norman Rockwell painting. He humanizes Jude and shows compassion in the style that Rockwell was known for. He lends his All-American style to the McCartney tunes and I really enjoyed the ride.

Cat Stevens/Yusuf – The Long and Winding Road

For me, this is the definitive song about the breakup of the Beatles. It’s beautifully crafted and melancholy at the same time. Yusuf brilliantly adds his brush strokes of beautiful tones with intelligence and dignity. Rembrandt would often paint people and his portraits would look into their souls and capture them. This version of “Long” does that for me. It’s full of compassion and conviction. I can tell that the meaning of this bittersweet McCartney song is not lost on the former Cat Stevens.

Harry Connick Jr. – My Love

This one is easy! Henri de Tolouse-Lautrec painted with class and grace, and “My Love” is such a smooth, dreamy kind of song. Connick is right on with the mood of the song and he adds a touch of class to the McCartney love ballad with easy flowing brush strokes on the canvas. As I listened to Connick’s “My Love”, I kept picturing the intimacy of Lautrec’s “In Bed.” A brilliant painting of love and innocence, it parallels the innocent and simple love that McCartney portrays in this song as he is convincing himself that “My love does it good.” This version of “My Love” is Lautrec painting “Water Lilies” with the same paint he used for “In Bed.”

Brian Wilson – Wanderlust

This was one of my favorites on the entire album. Brian Wilson captures this underrated McCartney tune with the enthusiasm of Winslow Homer and his amazing seascape paintings. Wilson brilliantly captures McCartney’s angst of love but at the same time there is that Paul trademark optimistic view of love as well. “Where did I go wrong, my love?” “What better time to find a brand new day?” The song is full of turbulence and uncertainty, and Wilson conjures images of waves and restlessness for our heartbroken victim, but you know that somehow, he will be ok. This version of Wanderlust is Winslow Homer painting the master Monet in a style of “Breaking Wave.” It’s brilliant!

Winslow Homer – Breaking Wave (Prout’s Neck) (1887)

Bluebird – Corinne Bailey Rae

This was too light and uninspired for me. She has a good voice, but she seems to not appreciate Monet’s contribution to the world. Rae is Marcel Duchamp, a French Dada artist. It’s emotionless and without heart. Bluebird deserves better.

Yesterday – Willie Nelson

The most covered song in history has a C.M. Russell quality to it. I never grow tired of this McCartney masterpiece. Yesterday is Monet’s “Water Lilies.” It’s beautiful and timeless. McCartney’s Lilies are painted by legendary country and western artist Willie Nelson. His rough voice lends respect and importance to McCartney’s words. He paints “Yesterday” with a quality of western art in a unique style that only Russell could paint “Water Lilies.” I have always loved how Russell can capture a moment in time and at the same time make the moment his own. That is exactly what Willie did here and it really works for me. It’s tender with a western edge.

Junk – Jeff Lynne

The former ELO front man paints a picture of Monet’s “Junk” with sharp, smooth abstract brush strokes like Diego Rivera. “Junk,” which was originally slotted for the White Album, is painted with love and devotion for McCartney. I enjoyed Lynne’s signature on this one and it shows how much the master influenced his music and artistry.

When I’m 64 – Barry Gibb

I found myself enjoying this version with its simple vocals and yet pleasing approach. This is Pop Art. Gibb is Andy Warhol here as he paints Monet. I am always surprised how much I like looking at soup cans when I think I shouldn’t, and Gibb sings “64” like Warhol paints. I know I shouldn’t like it, but I just can’t help myself.

Every Night – Jamie Cullum

“Every Night” is a gem from McCartney’s repertoire that deals with life as a Beatle – trying to create a balance between the rock lifestyle as a member of the biggest band ever and the desire to live a normal life. “But tonight I just want to stay in and be with you” typifies how McCartney felt at times when he was with the Beatles. Jamie Cullum has a thoughtful mix of vocals that betray both the frustration and the optimism that the song produces. To me, he is Paul Cezanne, pleasant and introspective.

Venus and Mars – Kiss

This remake is a perfect marriage as the rock band Kiss takes the McCartney classic and turns “Mars” into a Kiss song. Kiss is Jackson Pollock in this song as the paint/music is coming right at you with no apology. It is unordered and rebellious and that is what Kiss, McCartney and Pollock can be at their best.

Let Me Roll It – Paul Rodgers

This version has conviction and precision. It’s free-flowing. Henri Matisse painted people by capturing their essence, with jazz-like brush strokes that highlighted their bodies but made you look deep into their soul. “Let me Roll It” is Matisse’s “Le Rifain assis” to me. Rodgers and Matisse have always made art that is freelance and loose but at the same time with focus, clarity, and a personal touch. Rodgers/Matisse does a beautiful job here paying tribute to McCartney/Monet with his own unique style but at the same time reverence for his hero.

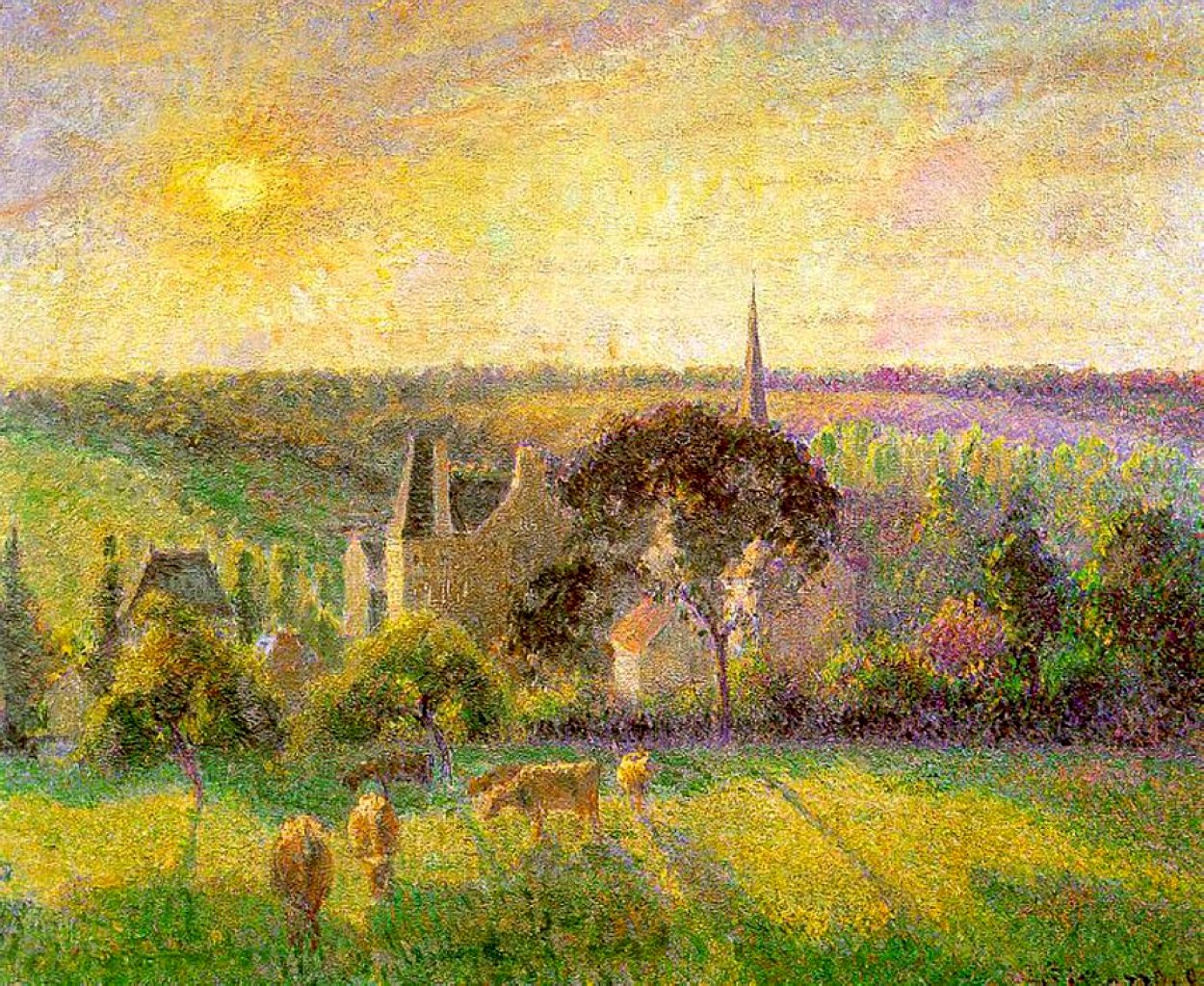

Helter Skelter – Roger Daltrey

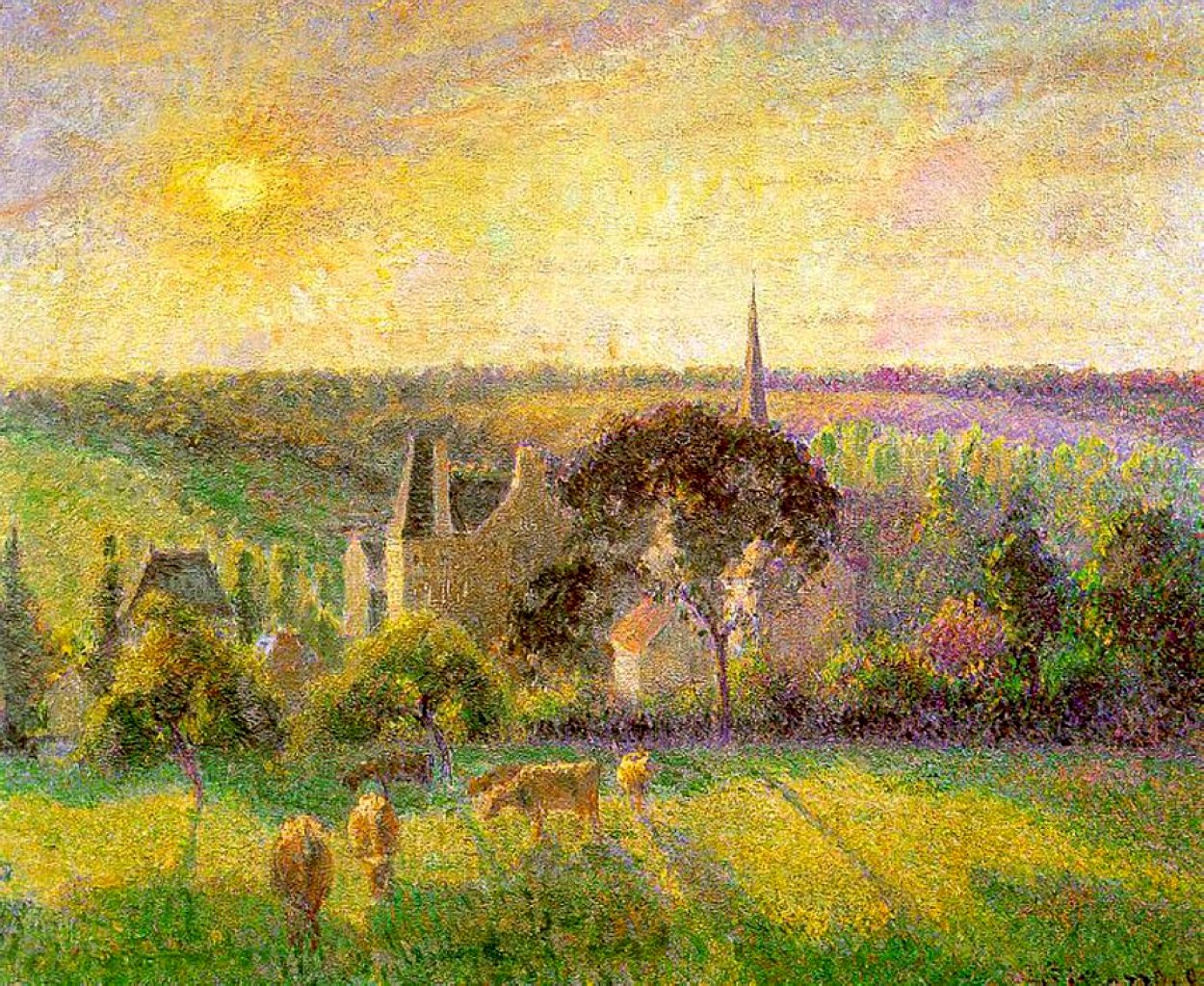

The Who’s front man packs a punch that is fierce, energetic and full of conviction on the Beatles classic “Helter Skelter.” Daltrey takes command of this song and makes it his own rock opera. Camille Pissarro would take a French landscape or a café in Paris and make it his own as well. Daltrey is Pissarro in every way to me in this song. Pissarro, like Daltrey to McCartney, was a contemporary of Monet and he had the utmost respect for Monet, but at the same time was very confident with who he was and his role in the French Impressionist movement. The Who have never apologized for who they are and they have created a very influential place in rock history alongside the Beatles. Roger Daltrey with “Helter” is Camille Pissarro painting Monet’s “Sunrise” in the style of “Eragny.” It’s bold, flaming colors and music coming right at ya. This is one of my favorite tributes on the entire albums as he honors McCartney and doesn’t compromise who is as an artist. That is who Camille Pissarro was and Roger Daltrey is: original, uncompromising and taking a backseat to nobody!

Camille Pissarro – The Church and Farm of Eragny (1895)

Hi, Hi, Hi – Joe Elliott/Helen Wheels – Def Leppard

Both interpretations of these Mac songs seemed very formatted; they lacked risk and originality. Elliott and the band seemed unwilling to take a risk, and very concerned to not disturb the original versions of the songs. Donatello (not the turtle) was always very detailed with his sculptures and also very concerned about sculpting exact replicas of his subjects, which were mostly historical figures like King David, Jesus and Mary Magdalene. I think Elliott’s admiration for his hero got in the way of his creativity and left these two songs uninspired and scripted. I would have been better off just listening to these McCartney songs and skipping these remakes. I’ll take Monet painting Monet over Donatello painting Monet anytime.

Hello Goodbye – The Cure/C Moon – Robert Smith

“Hello Goodbye” has been turned into a melted clock forever by the Cure. The Cure has created a dreamlike world with their music and they scream out Salvador Dali to me. Smith’s haunting, surrealist vocals splash the canvas of “Hello Goodbye” and “C Moon.” Dali could forever change perception of reality and that is what Robert Smith did with these two songs. He distorted the reality of these McCartney staples and put his own stamp on them, and I love it! Smith painted Monet’s “Jardin à Sainte-Adresse” with a Dali brush, and the end result is something new, exciting and unforgettable.

Let it Be – Chrissie Hynde

This McCartney masterpiece is one of Monet’s most famous and honored works. Chrissie Hynde lends beauty, imagination and insight to the canvas. This “Let it Be” pays respects to Sir Paul but at the same time the Pretenders’ lead singer adds spunk and spin to it. Like a beautiful painting that I can’t stop looking at, this version leaves me wanting to hear more of it. Hynde is Georgia O’Keeffe, the way she leaves a gorgeous impression with everything she sings. O’Keeffe’s style lends itself to immediate recognition – the moment you see one, you say, “That is an O’Keeffe.” That is what “Let it Be” is to me on this album. From the first note you say, “It’s Chrissie Hynde, wow, that’s beautiful. ”

Jet – Cheap Trick

Edward Manet would often get confused with Claude Monet because of just one letter that separated their last names. Well, there is no way you can confuse Cheap Trick with Paul McCartney but Cheap Trick to me is the Manet to Paul’s Monet. They are clean and fun and they have never taken their music too seriously. Manet would always paint people with certain a hint of mischief in their faces. His most famous painting, “The Spanish Singer,” depicts a Spanish singer who is playing his guitar in his torn shoes. Manet also caused a scandal when he painted a nude woman in “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” in 1863. Manet never took himself too seriously. There is always an underlying level of light atmosphere in both Cheap Trick and Manet, and “Jet” was performed like Manet paints; with a focus on his subjects but with a level of mystery about what they will do next.

Listen to What the Man Says – Owl City

This version of “Man” is too clean-cut and poppy for me. This did nothing for me. That is exactly how I feel about Keith Haring’s art. Owl City is uninspired Pop Art. This is Haring painting Monet — do I need to say more?

Got to Get You Into My Life – Perry Farrell

This is chaos with form. Farrell puts this magical Beatles song together with an abstract voice. It’s an abstract painting with colliding images, intelligently painted by Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky creating a Monet is pleasant to my ears and eyes, and it left me wanting to hear more of Farrell creating his Kandinsky of McCartney.

Drive My Car – Dion

Here is a marriage I thought I would never see: Dion, a 50’s original rocker, singing a McCartney song in 2015. There is nothing surprising here, though, as Dion lays the track with precision and a somewhat predictable singing style. He sings the song with clarity and respect; you can tell there is no doubt that McCartney has influenced him musically and this song was a way for him to pay his respects to the master. Dion is Rembrandt on this classic Beatles tune. Rembrandt would paint people of his time with respect and detail. That is what Dion does with “Drive My Car.” This is Rembrandt painting Monet’s “Self Portrait.” I can see in my mind’s eye the detail and devotion he put into the painting as he sings “Drive My Car” like sending a personal thank you to Paul and his inspiration. Dion was a pioneer in the late 50’s and early 60’s as he created a sound that is present in future works by many artists. The same can be said about Rembrandt. I think it’s fair to say that Rembrandt influenced Monet in a certain way and that Dion influenced McCartney and the way he approached his music as well.

Lady Madonna – Allen Toussaint

Allen Toussaint is a very respected jazz musician who is known for his unique, smooth voice and beautiful piano playing. He was a major contributor on McCartney’s “Venus and Mars” album and has the admiration of Sir Paul. I found this version of “Lady Madonna” to be understated and filled with beauty and soul. He captures feeling and mood in the song the way Edgar Degas would capture the heart and soul of ballet dancers in France. Degas’ trademark was his paintings of dancers, and I have always thought he was very underrated as a painter. He found beauty in the movement of dancers, and no two paintings of these dancers were alike. Toussaint found a way to create beauty with his jazz piano and velvety voice, and he takes “Madonna” and makes it his own. I was moved by what I heard. Degas adding ballet dancers to one of Monet’s French countryside paintings is what we have here with “Lady Madonna.”

Let Em In – Dr. John

Dr. John is one of a kind. I have never heard a voice quite like his and a style like his. He’s almost irreverent as he belts out the early Wings tune. It’s done with such a different tone that it works for me. This remake reminds me of the pointillism style that Georges Seurat would paint with. The way Dr. John barks out “Someone’s knocking at the door” is unique and it has his signature on it, just like Seurat would lend his signature to the specialized style of pointillism. These styles don’t work for most, but they both work for these art legends.

So Bad – Smokey Robinson

I have never been a big fan of this McCartney song. However, legend Smokey Robinson lends class and importance to this song. Smokey is Da Vinci, as he paints Monet with smooth acryclic paint and years of wisdom. He took a Monet painting that I didn’t especially like and put his own talent onto repainting into a beautiful work that only Da Vinci could paint. For me this is Da Vinci painting “Grainstack (Sunset),” lending it the passion with which he painted “St. John the Baptist,” with all its energy and devotion.

No More Lonely Nights – Airborne Toxic Event

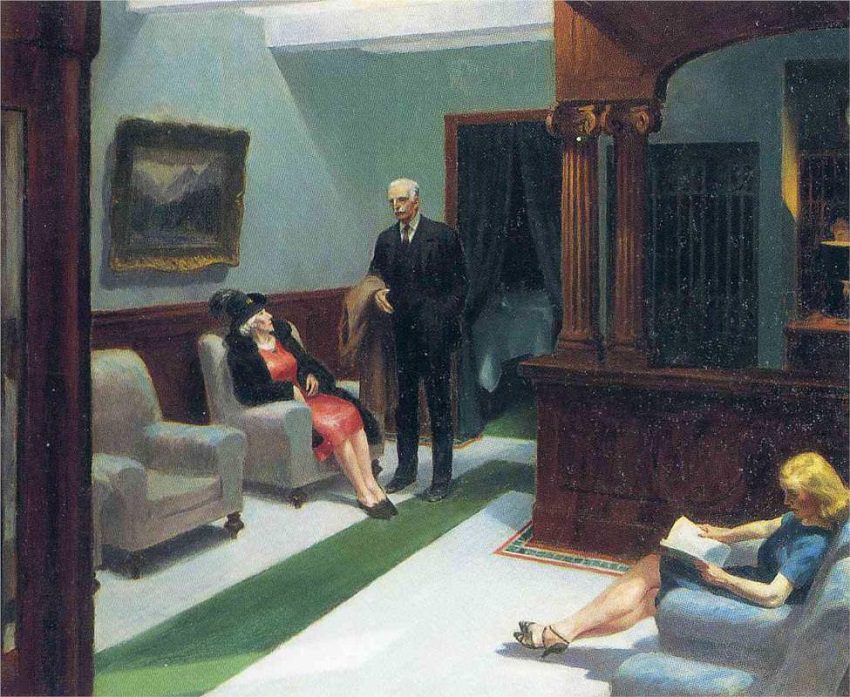

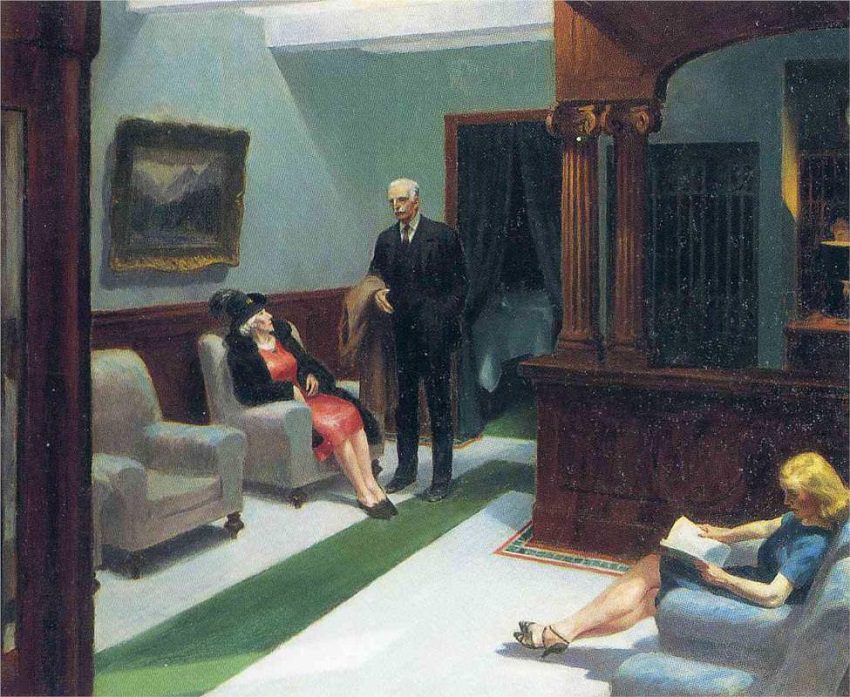

I really enjoyed Airborne’s take on this 80’s Mac tune. They sang this one like Edward Hopper paints. He paints with fresh, exciting colors that capture an ordinary place with new eyes and a new perspective. Take a look at Hopper’s “Nighthawks” and “Hotel Lobby” – that is what Airborne does with “Lonely Nights.” It’s an exciting new take. They seize the moment in “Lonely Nights” and take it! Hopper is a master at capturing moments as well. This is what it looks like to have Hopper paint one of Monet’s later works.

Edward Hopper – Hotel Lobby (1943)

Eleanor Rigby – Alice Cooper

It’s surreal to hear Alice Cooper sing “Eleanor Rigby.” Cooper has always been able to mix rock and roll with fantasy, and this version of “Rigby” was trippy and surreal to me. This is why Cooper is surrealist painter Rene Magritte in this song. Magritte would mix the dream world with the real world, and the result is Alice Cooper singing “Eleanor Rigby. This was the first thing I thought of, as this will be the closest I ever get to seeing what a Monet painting might look like if Magritte painted it.

Come and Get It – Toots Hibbert with Sly and Robbie

This is totally uninspiring and plain to me. This remake lets McCartney down. There is no creativity in this song. It’s plain and unremarkable. This is a Mark Rothko painting. Plain colors stacked on each other. The vocals are stacked on each other and it doesn’t belong on this album. Rothko has no business painting Monet and Toots and company have no business covering Sir Paul.

On the Way – BB King

This might be the best version of McCartney’s covers on this entire album. BB Kings sings with all he has! It’s poetic that McCartney developed this song off of McCartney II as a tribute to the blues and King honors this tune and the true spirit of its birth. There is no better person to play the blues than the King of Blues. King is Van Gogh on this tune as he made “On the Way” come to life with bright tones and vivid images. He paints “Water Lilies” with the fierceness of “The Starry Night.” It’s beautiful and timeless, and it’s a great tribute to BB King and the massive contribution he made to American blues.

Birthday – Sammy Hagar

I have always considered Sammy Hagar a bit on the abstract side. Stay with me for a minute before you scoff at my assessment. Everything he sings he puts his own spin on it and makes it his own. That is what an abstract artist does. “Birthday” is fun and it’s painted with Sammy abstract style and it puts a smile on my face. He is Paul Klee to me, painting Monet in a playful way. It’s like Klee painting Monet’s “Beach at Pourville” like he painted “Dancing Girl” or “Blossoms in the Night.” It would put a smile on my face.

Put it There – Peter, Bjorn and John

“Put it There” has never done much for me. Its tone is mundane and plain and I have never been very interested in its lyrics or musical arrangement and the overall feel for this song from Flowers in the Dirt. This is exactly how I feel about this updated version from Peter, Bjorn and John. It’s uninteresting, and does not do anything for me. I saw an exhibit many years ago of several artists at the Denver Art Museum. One of the featured artists was Carl Andre. His floor layouts and room sculptures left me completely unsatisfied and not interested at all. This is far from McCartney’s best work, but the trio did nothing to add to it. This is Carl Andre interpreting one of Monet’s lesser works.

This album was like walking through a Claude Monet exhibit that honored the great artist with remakes of many of his famous works redone by some of the world’s most famous artists. As I listened, I saw the interpretations in my head and it was one of the most fun journeys I have ever taken inside my head listening to an album. It also reminded me what a genius Paul McCartney is, and how he has changed the landscape of music for so many people. It’s impossible to measure the impact he has made on every person who loves the arts and the inspiration he has given to the world. Yes, the same can be said for Claude Monet!