NOTE: As usual for this series, Watchmen spoilers abound below.

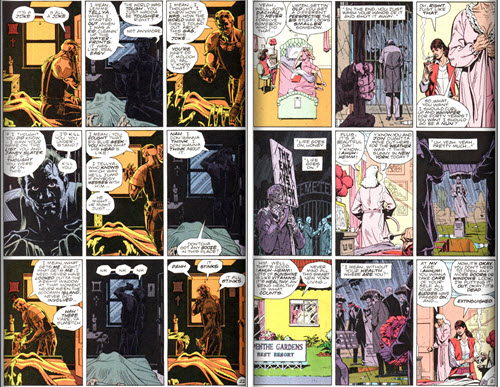

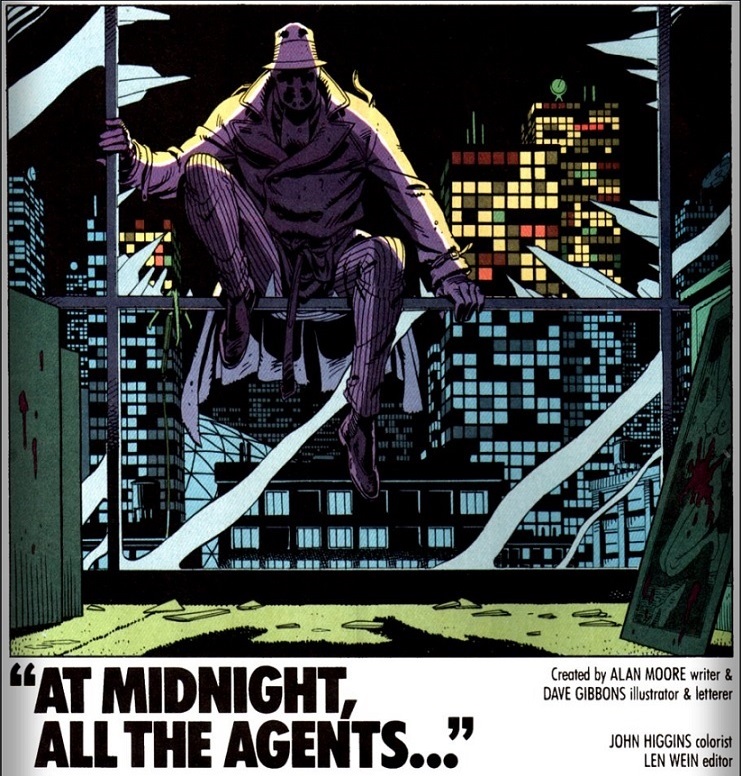

Moore and Gibbons’ cathedral has many symmetries and echoes. Here’s an important one for our purposes today: every chapter ends with an epigraph, and every chapter’s title is a piece taken out of its epigraph. Thus, each chapter hands readers a fragment at its beginning, then gives its full context at the end, inviting them to consider how that fragment in its context reflects upon what has come between. It’s an invitation well worth accepting, as each title and epigraph resonates richly on a variety of levels.

I certainly found that to be true of the Chapter 1 epigraph, from Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row.” Chapter 2’s epigraph comes from another song lyric, albeit one from just about twenty years later and across the Atlantic. The chapter is called “Absent Friends”, and the quote is from Elvis Costello’s 1984 song “The Comedians”:

And I’m up while the dawn is breaking, even though my heart is aching.

I should be drinking a toast to absent friends, instead of these comedians.

Pretty Words

At a glance, it would appear that the first part of this quote is actually a mismatch for the chapter. Dawn is never breaking here, either literally or metaphorically. Noir that it is, Watchmen is set mostly at night. Every Comedian flashback in this chapter takes place in a night-time scene1, as does Rorschach’s interrogation of Moloch. Although the funeral occurs during the day, it too is shrouded in rainy darkness. Only the panels with Laurie and her mother are in sunlight, and between John Higgins’ pastel palette and the scene’s contrast to the rest of the book, those panels seem absolutely sun-drenched, far from the early light of breaking dawn. And even in that sunny scene, dark emotions rule — Laurie and her mother spend most of it squabbling.

But what’s important about that first clause is the narrator’s position in it. He’s up while the dawn is breaking, which could mean one of two things — either he’s woken up before sunrise, or he’s been up all through the night. The former reading suggests ambition, a quality shared by several Watchmen characters. Ambition defines the members of the Minutemen, though their goals weren’t all the same. By the time of the Crimebusters meeting and the second generation of masked heroes, those differences of intent have gotten magnified enough that any kind of group unity is impossible — individual ambitions are pointed in radically different directions, none more so than Ozymandias, as that meeting sets in motion the main plot of the book. The Vietnam and protest scenes show the results of that fragmentation.

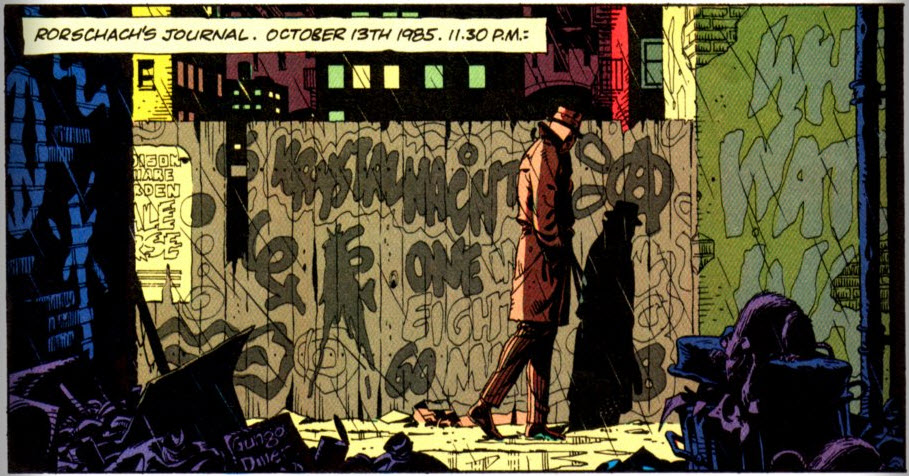

By the time of the final flashback, Rorschach is pretty much the only one with any ambition left, at least as far as we can tell at this point. The other heroes have retired, Moloch just wants to be left alone, and the Comedian is dead. Even though he’s the subject of the chapter, I don’t think the Comedian himself is up for consideration as the “I” in the quote, since the last part of the quote specifically mentions (and thereby excludes) him. Also, despite his presence in the flashbacks, he’s still dead — not exactly an early riser.

What about the other kind of “up while the dawn is breaking”, the kind where you’ve been up all night? That could suggest ambition in itself, or anxiety, or intensity, or just insomnia, but even more so it implies a separation from society — when the rest of the world sleeps, the narrator is awake long enough to see the dawn. Well, there’s certainly plenty of social deviance to go around in the Watchmen cast. By definition, the costumed adventurers are set apart from the rest of society, and Chapter 2 tells the story of how society gradually came to reject them. Even Doctor Manhattan, embraced by the government for his capabilities, is much more distant from humanity than any daysleeper.

I wouldn’t argue for a “correct” meaning between these two — the beauty of poetry is that both can be present at once, their implications and overtones harmonizing with each other. You could make the case that the “even though” pivot after the first clause suggests the ambitious reading, as the character would seem to be overcoming heartache in order to get himself moving, but I’d say that this pivot fits every reading. No matter the reason, all of these characters are pushing forward through emotional pain.

There may be no real dawn breaking, but heartache abounds. Both of the Juspeczyk women are suffering from isolation, even isolated from each other. In the flashback, Sally learns how little she’s valued among her teammates, while even the imposing Hooded Justice lives in fear of being outed. Captain Metropolis’s fear is evident in his display of “social evils”, and Ozymandias in that meeting feels “helpless against forces greater than any [he’d] anticipated,” as he explains much later. Nite Owl II still longs for the days when he could imagine himself “part of a fellowship of legendary beings.” Rorschach, as much as he tries to suppress any emotion, is lonely, and disgusted by the world around him. And Moloch, well, Moloch is not only isolated, frightened, helpless, and lonely, he’s also dying, and that laetrile is not going to help.

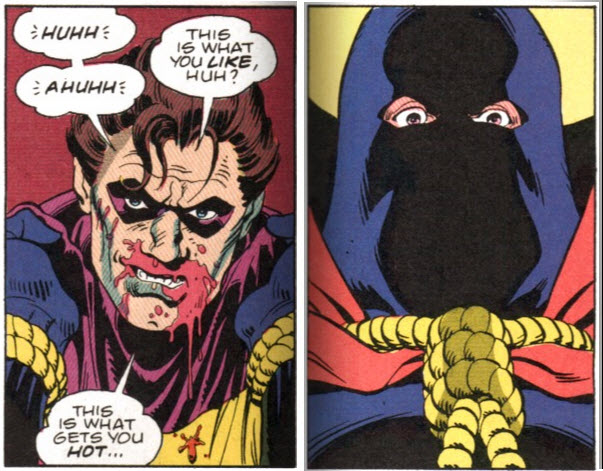

Ambition, social deviation, and emotional pain — the first line of the quote certainly fits what we’ve seen in the chapter. How about the second line? “I should be drinking a toast to absent friends, instead of these comedians.” The clearest denotation is of respect misplaced — the toast raised to the wrong subject. It’s easy to see the parallel here — Edward Morgan Blake is buried with full military honors, carried by top-hatted pallbearers, and attended by a pantheon of the most powerful people in the world. Yet as we come to know him through the flashbacks, he is a poison seed who makes every situation he’s in much worse for his presence. He takes advantage of the Minutemen’s innocence and cordiality to sexually assault a teammate. He destroys any chance that the second generation of costumed heroes could work together, though arguably there wasn’t much chance of it anyway. He insults and belittles Ozymandias in a way that tips him over the edge into planning mass slaughter. He guns down a woman pregnant with his child, launches tear gas into a crowd of protesters, confuses the hell out of Moloch (without revealing the rather crucial information that Ozymandias is the source of Moloch’s cancer), and unwittingly sets his own death into motion by giving his “last performance” to a room bugged by Adrian Veidt.

“These comedians” — the reference is plural in the song, but it’s plainly meant to refer here to the singular Comedian — don’t deserve our time and respect, but who does? Absent friends. This is the crux of the quote, which is why Moore chose it for the chapter title. The central themes of this epigraph are loss and isolation, and Chapter 2 of Watchmen shows us the reasons for the characters’ isolation from each other, and what they’ve lost along the way.

History Repeats the Old Conceits

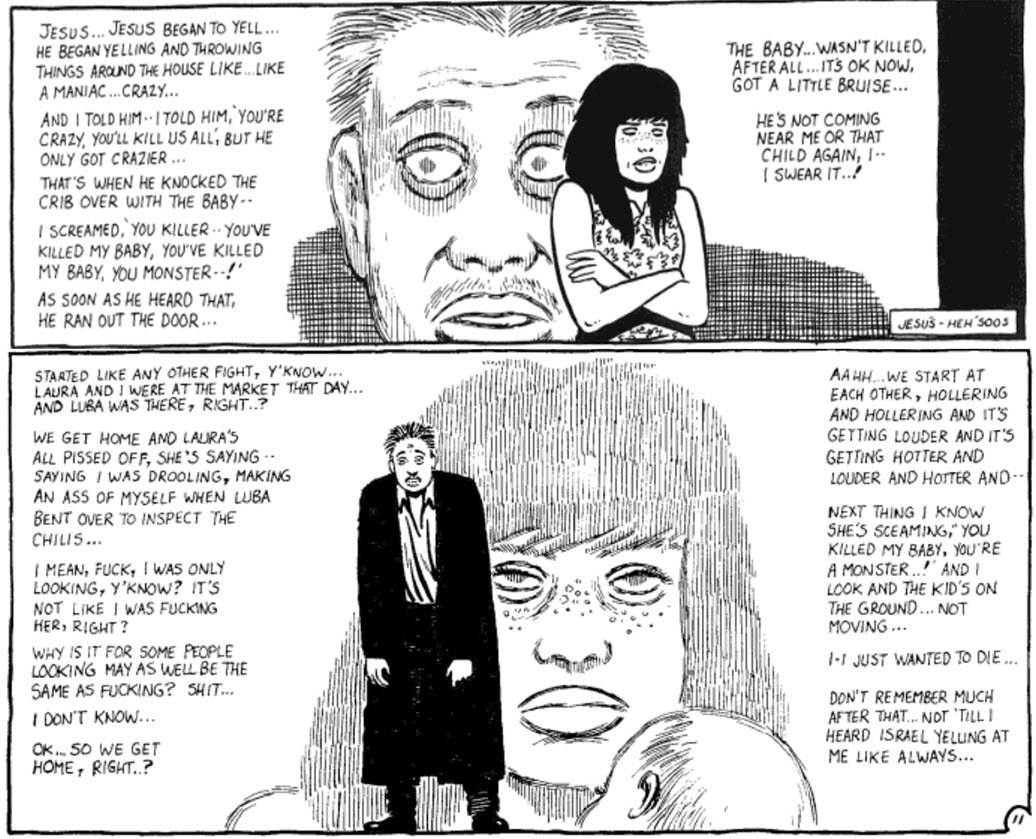

If Chapter 1 introduces the characters to us, Chapter 2 introduces their history, and their world. Moore’s ingenious structure ensures that no chapter (for that matter, almost no panel) is doing just one thing, so only the most obvious function of chapter 2 is to deepen our understanding of The Comedian. As I reviewed in the previous post, the chapter does this by showing the character to us through the eyes of his community.

However, by moving forward in time, those flashbacks also tell the story of that community and its world. That story starts when masked heroes were a fad, and there was some sense of camaraderie between the Minutemen. These heroes were friends, or at least some of them believed they were, enough for Nite Owl to chummily invite the gang over for beers. The first break we see in those bonds comes when The Comedian attacks Silk Spectre, and is attacked in turn by Hooded Justice, who then shows no sympathy for the Spectre’s plight.

26 years later, at the time of the next flashback, the Minutemen are gone, and with them any sense of a group dynamic. Liaisons still exist, but they tend to be dyads — Nite Owl II and Rorschach, or Dr. Manhattan and his wife Janey (soon to become a dyad of Dr. Manhattan and Silk Spectre II.) Thus the friendships of the 1940s are already absent in the 1960s, despite Captain Metropolis’s attempts to recapture them.

In the 1971 Vietnam flashback, connections have eroded still further. The government has co-opted the activities of two costumed adventurers and sent them off to join a war effort, just as The Comedian had hoped for in 1940. Thus these two adventurers are cut off from the rest of their brethren by both intention and distance. Moreover, Dr. Manhattan himself is becoming a friend to no one — as The Comedian observes, he’s drifting out of touch.

The characters are alienated from each other, and some alienated from humanity in general. The 1977 police strike protest flashback shows us the culmination of humanity’s alienation from them. Where at first vigilantes were seen as a welcome addition to police efforts, and then as a useful tool for national interests, by 1977 they are being rejected outright by the police, with that rejection supported by an angry grassroots movement. Any sense of friendship between the masked heroes and the public they ostensibly serve is long gone, and their connections to each other have broken down further, as Nite Owl II looks on in horror at The Comedian’s actions, and mutters that Rorschach “mostly works on his own these days.”

Come 1985, Rorschach is the only vigilante left active, and thus is officially absent from Blake’s funeral, lest he be recognized and detained. Like Moloch, he can only pay his respects in secret. Laurie, on the other hand, has no wish to pay any respects at all, and Sally is apparently not invited. The dyad of Dr. Manhattan and Silk Spectre II is breaking down, and she has not yet become attached to Nite Owl II.

Thus at the time of this chapter, all the characters are isolated from each other. It’s not just that friends are absent — friendships are absent. Ironically, just has he helped to break them apart in life, The Comedian in death helps to bring them closer together, with Rorschach visiting each of them, and a subset of them gathering at the funeral. Thanks to Blake, Ozymandias is about to bring them all closer still.

This Year’s Model

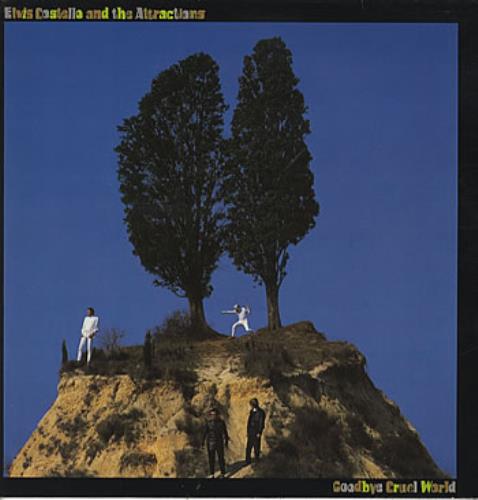

“The Comedians” comes from Costello’s 1984 album Goodbye Cruel World. Overall, it’s a bit of an odd song. With a 5/4 time signature, it’s not exactly American Bandstand material, and its impressionistic, elliptical lyrics resist the interpreter’s grasp. In the liner notes to his 2004 reissue of Goodbye Cruel World, Costello writes that the song “takes its title from a Graham Greene book but other than that has no connection with his work.” So that’s one thing it has in common with Moore’s Comedian.

He also claims that the lyric “has something to do with temptation without being too specific.” That’s putting it mildly — references to temptation are extremely oblique if indeed they’re present at all. For my money, a clearer single-word précis would be “disillusionment.” Falling under gentle persuasion might qualify as being tempted, but lines like “they’re finding all that glitters is not chrome”, “what kind of love is this upon inspection”, and “all these newfound fond acquaintances / turn out to be the red rag to my bull” speak much more loudly to a sense of deception and disappointment. Cast in that light, the misplaced honors of the chorus seem to result from a series of mistakes on the narrator’s part.

According to his liner notes from the previous Goodbye Cruel World reissue, in 1995, Costello was feeling plenty of disillusionment himself in 1984. For example: “Many very private and personal concerns influenced the fate of these songs and sessions… It must suffice to say that I began the year as a married man and after a fraught and futile period, I found myself living alone by the time this record was released.” Moreover: “‘Pop Music’ was among the things about which I was depressed and demoralized.”

This album represents a crossroads in Costello’s career. After Declan Patrick MacManus adopted the name “Elvis Costello”, he burst onto the scene in 1977 as more or less an instant star, racking up an unbroken run of 8 singles in the UK Top 30. After his first few years, though, Costello began to wander into the valley tread by many a pop idol, albeit each in their own way. He recorded an album of all country music covers. His band The Attractions had started to shake itself apart, with relations especially tense between himself and bass player Bruce Thomas. And he managed to alienate just about everyone with his behavior in a Columbus, Ohio Holiday Inn bar.

That night in April 1979, Elvis and The Attractions were sharing the bar with Stephen Stills’ touring band. Costello claims to have been so drunk that he has no memory of the proceedings, but they are recounted more or less as follows. Costello began needling the Stills crew, with a motivation he speculates about in autobiographical hindsight: “My guess is that I had developed the rather juvenile view that the previous musical generation had squandered their inheritance and I started to believe we had been sent to sweep it all away.” (pg. 336) In any case, he antagonized them, they antagonized him, and the whole scene wound itself up to a ridiculous alcohol-fueled pitch, until Costello tried to “provoke a bar fight and finally put the lights out” by tossing off despicable racial slurs about James Brown and Ray Charles. He got the fight he wanted, as Bonnie Bramlett socked him in the mouth and the whole party collapsed “into a heap of flailing limbs that only ended when the barman came around the counter with a raised baseball bat.” (pg. 335) The whole thing would probably have just made for a silly tour story, except that Bramlett went on a radio call-in show the next morning, told her side of the story, and suddenly Elvis was national news as a horrible racist, banned from radio playlists and overwhelmed with death threats.

Costello has explained himself several times, in several different venues. He says that he was “speaking the exact opposite of [his] true beliefs”2, that it was “an absurd overstatement of opposites, a contradiction in terms” (pg. 336), and that he was “speaking in some absurd, exaggerated, supposedly ironic humour, in which everything is expressed in the reverse of that which one knows to be true.” Not to mention “drunken”, “idiotic”, and “completely irresponsible.”3 I believe him on all counts. There’s nothing else in his career or public persona to suggest racial bias, and plenty to suggest quite the opposite. What’s most important about the story today is the way it derailed him and caused the beginning of a spiral — he’s aptly compared it to Dylan’s 1966 motorcycle crash in the way it stopped the madness of the life he had been living, albeit in a very self-destructive fashion.

There are more parallels between Costello and Dylan, but we’ll get to that in a minute. I was mentioning how Goodbye Cruel World was a crossroads album for Costello, and the stories above are a bit of background for that assertion. There’s more. Another way in which Costello began to wander after his first several albums was in his choice of producer. The first five Costello albums saw Nick Lowe at the helm, but for the country covers record he went with a Nashville producer, and for the one after that he partnered with Geoff Emerick, the legendary engineer who worked on (among other things) Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s, the White Album, and Abbey Road. That album (Imperial Bedroom) was an artistic triumph, but was less successful on the charts — neither of its singles cracked the UK top 40, and they weren’t even a blip on the US charts.

Enter Clive Langer (nicknamed “Clanger”) and Alan Winstanley. This duo had seen quite a bit of UK success producing several albums by Madness, and the breakout debut Too-Rye-Ay by Dexy’s Midnight Runners. They produced Costello’s 1983 album Punch The Clock, and gave him a considerable international hit with “Everyday I Write The Book.” The song brought Costello back into the UK Top 30, and gave him his first ever entry into the US Top 40. Rock critics hailed “Everyday” as Costello’s comeback.

So when it was time to record Goodbye Cruel World — the follow-up to Punch The Clock — Langer and Winstanley were seen as the obvious choice to produce. The problem was, Costello wasn’t on board. As you may recall, he was depressed and demoralized about pop music, and morose specimen that he was at the time, he “fought every attempt to apply the Clanger/Winstanley method to these songs.”4 “So in the end,” he says, “we agreed to a truce. Clive and Alan would produce two selected songs to the height of style and I could make the rest of the record as miserable as possible.”5 Neither of those two songs (“I Wanna Be Loved” and “The Only Flame In Town”) made anywhere near the splash that “Everyday” had, and Costello ended up dissolving The Attractions (though they’ve sporadically reunited over the years), and swerving into a journey of genre experimentation that has so far included chamber music, soundtracks, a ballet score, and concept albums, as well as collaborations with such artists as Paul McCartney, Allen Touissant, Burt Bacharach, and The Roots.

That swerve was still in the future when Alan Moore was writing Watchmen. “The Comedians” was a very contemporary reference in that comic — the album couldn’t have been much more than a year old while Moore was drafting Chapter 2. The fact that he chose a Costello quote to follow a Dylan quote in the book highlights the comparison between the two artists. Costello is in some ways the UK’s answer to Bob Dylan — a musically restless maverick with a supreme gift for well-turned and provocative lyrics. They’ve both had a combative relationship with the press over the years, and with their fans as well. Critic Larry David Smith comes right out and says it: “Elvis Costello is an English Bob Dylan: an irrepressible rebel who will reject you because you praise him, who feels artistic recognition is the harbinger of creative stagnation, and who — more than likely — battles with himself. The result is one impressive body of work.” (pg. 125)

But where Dylan came out of the early 1960s folk song tradition, Costello’s vintage is rather different: the late 1970s punk tradition. Smith in fact makes much of calling Elvis a punk no matter what genre territory he traverses, declaring Costello the creator of such oddities as the punk torch song, the punk chamber music record, the punk lounge album, the punk editorial, and so forth. This may all be a little overblown, but when Smith stakes out his definition of “punk” — melodramatic, irreverent, aggressive — it’s hard not to find those qualities in the lion’s share of Costello’s output.

Still, although he came of age in the midst of the punk movement, and was deeply influenced by it, Costello doesn’t easily slot into the punk stereotype. His thick glasses and knock knees of 1977 were a far cry from the jagged aggression of The Sex Pistols, the street tough aura of The Clash, or the horror-carnival aesthetic of The Damned. Like his contemporaries, Costello had venom to spare, but he also brought a highly literary sensibility to everything he created — layers and layers of wordplay, allusions, clever metaphors, and poetic imagery.

As so often happens in these Watchmen articles, this is all starting to sound a bit familiar, isn’t it? I made the case in a previous post that Alan Moore is the Bob Dylan of comics, but the more I’ve learned about Elvis Costello, the easier it’s become to see the Costello sides of Moore as well. For one thing, we know that Moore is a punk rock aficionado. In a 2015 interview with Pádraig Ó Méalóid, Moore declares his enthusiasm for punk rock, and goes on to boast, “I doubt that there’s many people out there with a better collection of early punk vinyl singles than I’ve got.” Later on he specifically cites his admiration for Costello, placing him alongside bands like X-Ray Spex and The Clash.

So is Moore a punk comic writer? Well of course that all depends on whose definition of “punk” we’re using. Smith’s triumvirate of aggression, irreverence, and melodrama don’t fit all that well as a description of Moore’s work, but then again I’m not sure I’m all that swayed by Smith’s definition of punk. Those three things all come into play in punk rock, but I would argue there’s a deeper linchpin beneath them: the spirit of resistance. Punk came about as a rebellion against the polished and often bloated popular music of the mid-1970s, and the general sound tended to combine a throwback to the garage rock sounds of the late ’50s and early ’60s with a snarling, pissed-off tone that was beyond anything rock had consistently manifested up until then.

The individual songs also tended to display some kind of rebellion or resistance, be it political, social, cultural, or — as is frequently the case in Costello’s oeuvre — romantic. You don’t find many punk songs celebrating something, unless it’s celebrating the spirit of destruction, a la “Anarchy in the UK.” Instead, the punk project is to take apart the status quo and replace it with something more authentic and true.6

Framed like that, our notion of punk starts to get closer to the spirit of Moore. He hit his stride in 1982 with Marvelman, which dug beneath the superhero concept to interrogate the connections between power, fear, mythology, perfection, and control. V For Vendetta, Swamp Thing, The Ballad Of Halo Jones, and lots of other stories soon followed, including some brilliant reinterpretations of characters like Superman and Batman. Each of these works, up to and including Watchmen, took an established status quo of some kind, deconstructed it, and emerged with a startlingly fresh new approach. If there’s a through-line to Moore’s work, it is his tendency to upend whatever genre, convention, character, or milieu he finds, replacing it with something more authentic and true.

So yeah, I think it can fairly be said that Alan Moore has a punk spirit, and that this spirit expressed itself in Watchmen. Like the epigraph he chose for this chapter, Moore knows something about respect misplaced, and like Costello himself, he wields linguistic virtuosity in the service of his rebellious projects. He’s never been punched for drunken racist remarks (that I know of), but then again he did start worshiping the snake-god Glycon on his fortieth birthday — everybody finds a different way to crash that motorcycle.

Black And White World

Larry David Smith has painstakingly categorized all of Costello’s songs (up through 2004) into classifications like “Relational Complaint”, “Relational Assault”, “Wordplay”, and “Narrative Impressionism”. In his rubric, the majority of songs in Costello’s first ten years fall into some relational category, and generally in the negative — complaint, assault, warning, plea, struggle, etc. As I learned when listening closely to his debut My Aim Is True, he’s angry and hurt, mostly about women.

But there’s another category that, while a minority of his output, still appears on most of his records: the societal or political complaint. It’s there from the beginning — his very first single “Less Than Zero” was was a shot at British fascist Oswald Mosley — and probably culminates in “Tramp The Dirt Down”, from the 1989 album Spike, in which he fantasizes about outliving Margaret Thatcher so that he can stomp on her grave. Costello seemed to have a particular animus toward Thatcher, so much so that academics David Pilgrim and Richard Ormrod were able to write an entire book called Elvis Costello And Thatcherism.

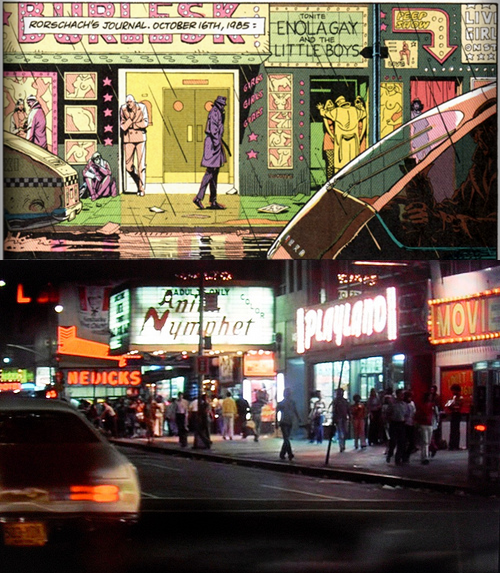

I’d argue that Thatcherism is an important topic for looking at Watchmen, too. Moore said midway through the release of Watchmen that part of his aim with the book was to “try and scare a little bit so that people would just stop and think about their country and their politics.” Watchmen wasn’t a direct commentary on British politics the way that V For Vendetta was — in fact, the entire thing is set in America and barely mentions any other countries at all, except for Vietnam, Afghanistan, and the USSR. Some of its themes, however, relate directly to Thatcher’s agenda — privileging the individual over society, a manichean view of morality, aggressive foreign policy, and what Costello called an “enthusiasm for Cold War posturing.”7

Pilgrim and Ormrod speak of Thatcher’s “fetish for the individual rather than society,” (pg. 9) and in this she was a fine avatar of right-wing politics, which tends to favor individual rights and actions over notions of a “social contract” and collective actions — hence the right’s enthusiasm for tax cuts, dismantling government apparatus, and eliminating “entitlements”. (Though there are some huge caveats in that philosophy as it played out under Thatcher and Reagan, as we’ll see below.)

Something of that same tension rears its head in the 1977 police strike flashback in Chapter 2 of Watchmen. “We don’ want vigilantes! We want reg’lar cops!” shouts a guy whose shirt might as well read “proletariat.” The strike is essentially the police saying “you want to handle crime as individuals? Go ahead. Good luck with that.” The Keene Act which arises from the resulting unrest is a reassertion of centralized social order over individual libertarianism, and what it represents for the genre is a fundamental challenge to the concept of superheroes.

That same question has been re-explored in superhero stories ever since, the most salient recent example being Marvel’s Civil War event and the Captain America movie patterned after it. Should we as a society allow individuals with their own agendas to act unilaterally and violently to enforce their values, or must we find a way to co-opt their actions? The conflict continues to play out in Watchmen through the oppositional viewpoints of Nova Express and The New Frontiersman. Those two publications, representing the left and the right respectively, see superheroes as an existential threat to democracy on one side, and the perfect expression of freedom on the other. That The New Frontiersmen compares the KKK favorably to superheroes, and that Moore shows us one individual’s actions causing millions of deaths, in the name of a peace we know can only be fragile and temporary, gives us a pretty good clue as to where he stands on the argument. Right?

Except… in V For Vendetta, it is the vigilante who is the hero, taking on a corrupt and oppressive dystopian regime. There, the “reg’lar cops” are complicit, and not to be trusted — much more of a threat than crime, as Evey learns in the first few pages. So maybe Moore isn’t so easy to pin down after all. Or maybe Watchmen was a form of second thoughts after V For Vendetta. The British government of V is horrific, but the American government in Watchmen is no treat either, especially in light of how it presages Moore’s later screed in Brought To Light. Yet V’s attacks are shown nobly, while Ozymandias’ unilateral vigilantism is abhorrent, as the first six pages of Chapter 12 make very, very clear.

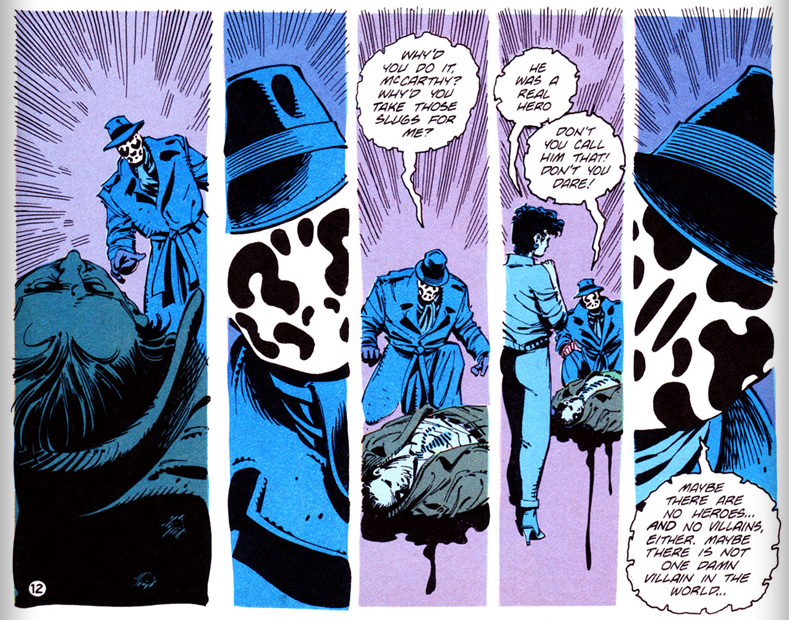

But even that argument is an oversimplification. The truth is, neither V nor Ozymandias fits simply into a hero or villain mold, and one of the things both works have in common is that they problematize the notion of heroism, and open questions about where the lines are drawn between resistance and terrorism, between destroying lives and saving the world. It’s complicated, is what Moore is telling us, and attempts to make it seem otherwise are generally meant to manipulate you into compliance.

Moral complexity was never high on Margaret Thatcher’s list. She was a lay preacher in the Methodist church before her entry into politics, and she saw a clear connection between her economic policies and her religious beliefs. Just as the Republican party in the U.S. allied itself in the 1980s with social conservative organizations like Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, so too did Thatcher pursue her own social conservative agenda, such as banning discussion of homosexuality in public schools8 and clamping down on the distribution of “nasty” videocassettes.

This is one of the paradoxes of Thatcherism, and Reaganism too for that matter. On the one hand, their philosophies proclaimed the the people’s rights to individual liberties. On the other hand, when it came to matters like who to marry, what to watch, and (especially in the US) legal access to safe abortions, individuals suddenly found their liberties sharply curtailed. As it turns out, while their administrations may have had a libertarian sheen, Thatcher and Reagan were more interested in the freedom of money to go where it wanted without state interference, and in the freedom of corporations to do what they wanted without regulatory interference. The people who worked for those corporations, well, they were free to come to work, but God help them if they tried to unionize, because their government was dead set against it.

Costello works through some of these same themes from a different angle in “Pills And Soap”, a song from Punch The Clock. It turns out that Costello also borrowed a superheroic trope for this song, releasing it not as Elvis Costello (already an alter ego for Declan MacManus), but as “The Imposter”, an alter ego for Elvis Costello. The lyrics themselves aren’t straightforward, but its central image of children and animals melted down to create the titular pills and soap certainly evokes the fascist British concentration camps of V For Vendetta. What made it particularly political was its release, under a pseudonym, shortly before the 1983 UK General Election in which Thatcher’s Conservative party was challenged by Labour. As it happened, the Tories (Conservatives) in that election gained 38 seats while Labour lost 58 — as Costello says in the 2003 Punch The Clock liner notes, “It was released for a limited period only and melodramatically deleted on the eve of the 1983 General Election. The need to re-issue it the following day on a celebratory red vinyl 12″ sadly never arose.”

As for moral simplicity, the most relevant Costello song is probably “Black and White World”, from Get Happy!!. That song’s primary metaphor is about comparing modern life to old films (i.e. the black-and-white world of pre-Technicolor movies), but with Costello’s usual aptitude for double meanings, it also carries a connotation of black-and-white morality, in lines like “There’ll never be days like that again / When I was just a boy and men were men.”

Where we might find a black-and-white view of morality in Watchmen? The answer seems fairly obvious, though his version of “when I was just a boy and men were men” sounds more like “They could have followed in the footsteps of good men, like my father and President Truman.” Rorschach, as we saw in our examination of Steve Ditko’s Charlton characters, is a reflection of The Question’s Objectivism, and ironically his opposition to Veidt cuts through the Gordian Knot of the Thatcherist paradox in a punk spirit, by reasserting the individual’s right to resist.

Peace In Our Time

Costello’s primary critique of Thatcher focused on her military adventurism, especially the 1982 Falklands War, in which Britain charged to the defense of some tiny islands in the South Atlantic, overseas territories left over from the high times of British colonialism in the 19th century. Argentina asserted (and still continues to assert) its sovereignty over these islands (which it calls the Malvinas), and in April of 1982 sent a force to occupy them. Thatcher’s Britain responded with a naval task force, and a 74-day conflict ensued which resulted in 907 casualties.

Liberal Brits like Costello were dismayed to see their country at war, especially in acts like the sinking of the Argentine ship General Belgrano, which was torpedoed while retreating. 321 Argentinians died in that incident, accounting for just about half the Argentine losses in the war. Meanwhile, British casualties reached the hundreds as well. Costello’s forceful response was “Shipbuilding”, a song he wrote with Clive Langer. Costello’s lyrics paint the picture of a small town whose economy depends on the jobs created by the business of constructing ships. Yet that same small town will be sending its young men off on those ships, possibly to die in conflicts like the Falklands War. Langer and Costello gave the song to British singer-songwriter Robert Wyatt, who released it in 1982 (in a single produced by Costello) to little response, but had a top 40 UK hit a year later when re-releasing it for the first anniversary of the war.

Costello released the song himself on 1983’s Punch The Clock, with a memorable trumpet solo by Chet Baker included. Alongside “Pills And Soap”, it made Punch a more political record than Costello had released in years. Goodbye Cruel World continued the trend. Songs like “The Great Unknown”, “Joe Porterhouse”, and even “The Comedians” itself had content that could easily be taken as political, though often other interpretations were possible as well. The final track, though, was unambiguous.

“Peace In Our Time”, like “Pills And Soap”, was released as a single by The Imposter, rather than Elvis Costello. It takes a wide-scoped view of war, with each verse dedicated to an era of conflict. Verse one references Neville Chamberlain‘s doomed Munich Agreement and the spectre of World War II, while reflecting that now Costello dances in Italian shoes to German disco music. Verse two cites Cold War anti-Communist hysteria, and the horrible possibilities of nuclear annihilation.

Finally, verse three discusses events that were current at the time. “Another tiny island invaded” could refer to the Falklands or to Reagan’s invasion of Grenada. “International Propaganda Star Wars” was a swipe at the US’s proposed Strategic Defense Initiative, which hoped to provide an anti-nuke “missile shield.” And the reference to spacemen in the White House addressed both the Presidential candidacy of John Glenn and Reagan’s supposed mental deficiencies.

After each of these evocations of conflict, the chorus repeats:

And the bells take their toll once again in a victory chime

And we can thank God that we’ve finally got peace in our time

The irony is layers deep here. For one thing, the title phrase connects directly with the image of Chamberlain in the lyrics:

Out of the aeroplane stepped Chamberlain with a condemned man’s stare

But we all cheered wildly, a photograph was taken,

As he waved a piece of paper in the air

There is indeed a famous photograph of that moment, Chamberlain just having returned from Germany with an agreement to allow Hitler to annex Czechoslovakia in exchange for peace between the UK and Germany. Even more famously, Chamberlain said that day, “I believe it is peace for our time. We thank you from the bottom of our hearts. Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.” Hitler continued invading countries, and less than a year later the UK was at war with Germany. Today the phrase is mainly remembered (and slightly misquoted) ironically.

From that initial irony, we get the additional fact that the chorus repeats after every cycle of war in the verses. Though a chorus of victory chimes may ring over and over, and though we may declare that peace has arrived at last, there’s always another verse of battle just around the corner. Finally, there’s a play on “toll” — bells toll, but they don’t “take their toll.” Wars do that, and the peace they bring to many is the peace of the grave, over which funeral bells ring.

And now we’re back to Watchmen, in which The Comedian is the first casualty of Ozymandias’ peace campaign, a “practical joke” which he believes will bring lasting peace, not seeing how closely he resembles Chamberlain in front of that aeroplane.

In the liner notes for the 1995 reissue of Goodbye Cruel World, Costello writes of the song, “If it now seems like a relic of those days of anti-nuclear dread then I hope it stays that way.” On the next reissue, he says, “Writing in the late spring of ’04, the title of this piece seems a more distant prospect than ever. I have to hope that this flawed song doesn’t sound like a sick joke by November.” Much like in 1983, I don’t think Costello got the result he was hoping for. I doubt Ozymandias does either.

Next Entry: Costumed Cut-ups

Previous Entry: Absent Friends

Endnotes

1Granted, the first one takes place entirely indoors and there is no supplemental information elsewhere in the book to elucidate the time. However, there are a few hints that, taken together, strongly suggest that this is a night-time scene. First, the window on panel 1 of page 5 shows only darkness. Second, Night Owl suggests that they “go back to the Owl’s Nest for a beer”, something less likely to happen in the middle of the day. Finally, the clock in panel 9 of page 7 shows (of course), a few minutes to 12:00, which given the previous two clues is much more likely to be midnight than noon. Moreover, we know from Under The Hood that Hollis Mason’s police work was his “day job”, and his superheroing took place mostly at night, hence his nickname. All these factors combined make me confident that the first Comedian flashback in Chapter Two takes place close to midnight. [Back to post]

2In the liner notes to the 2002 reissue of Get Happy!!, an album of Motown-style songs that he released after the incident. [Back to post]

3All from a 1982 Rolling Stone interview with Greil Marcus. [Back to post]

4Liner notes to the 1995 reissue of Goodbye Cruel World. [Back to post]

5Liner notes to the 2004 reissue of Goodbye Cruel World. [Back to post]

6In fact, as I argue in my post about London Calling, one of the ultimate expressions of punk rock was The Clash’s rebellion against the shibboleths of punk rock itself. [Back to post]

7Liner notes from the 2003 reissue of Trust [Back to post]

8This, too, is complicated by the fact that early in her political career, Thatcher voted to decriminalize abortion and homosexuality. Her later swing towards social conservatism may have been more a matter of practicality than of conviction, or it could have been a genuine change of heart. With politicians it’s hard to tell, isn’t it? [Back to post]