[GM Note: There are spoilers in this article for Watchmen and the Watchmen-related materials produced for Mayfair Games, as well as HBO’s Watchmen series. Readers who don’t know this material and encounter these spoilers must make an INT action check against an OV/RV of 9/9 with a two column shift penalty or suffer 5 APs of disappointment.]

In 1972, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson had an idea. What if you took the rules and mechanics of the board wargames they both loved, and adapted them so that players would control not only pieces, but actual characters in a story? The result was a new beast, a “role-playing game” (RPG) called Dungeons & Dragons, which gestated slowly throughout the 1970s and by 1980 blossomed into a full-blown cultural phenomenon. In 1982, D&D even showed up in E.T.: The Extraterrestrial, still one of the most successful movies of all time.

So of course, as the Eighties rolled on, everybody wanted a piece of that sweet D&D action. Sure, the trailblazing game was set in a fantasy milieu, but no doubt there would be lots of other fun genres in which RPGs could romp, right? D&D‘s publisher TSR Hobbies was already on that train, producing Top Secret (a spy RPG), Gangbusters (1920s crime), Star Frontiers (sci-fi), and Boot Hill (western), among many others. Superheroes were ripe for development, but unlike the aforementioned genres, they were more dependent on character than on setting, and the dominant sets of character IP were owned by the Big Two comic book companies, DC and Marvel.

TSR solved this problem in 1984 by acquiring the Marvel license and producing the Marvel Super Heroes RPG. But they could hardly play both sides of the field, so that left DC to partner with one of TSR’s many competitors. They found a match in Mayfair Games, which had started out publishing railroad-building boardgames, but ventured into the RPG craze with Role Aids, a line of adventure modules and supplements advertised as compatible with D&D. (Not surprisingly, this marketing tactic later got them into legal hot water with TSR. At least they never got sued by Rolaids.)

Be Part Of The Legend!

Thus it was that in 1985, Mayfair released the DC Heroes role-playing game. That game’s tag line was “Be Part Of The Legend!”, and its cover (gorgeously drawn by George Pérez) featured some marquee Justice League heroes along with the New Teen Titans — DC’s hottest team at that time — battling a legion of villains.

This game faced a daunting design challenge, because some of that era’s DC characters were ludicrously powerful — for instance, Superman once destroyed a solar system by sneezing. How to represent such off-the-charts power alongside guys like Batman, who was essentially a peak athlete with wonderful toys? Designer Greg Gorden ingeniously married these extremes by introducing a logarithmic scale for game stats. Everything in the game gets measured in Attribute Points (AP), and every attribute point is worth twice as much as the one before it. As the manual explains, “Therefore, a DC Hero with a Strength of 6 is twice as strong as a DC Hero with a Strength of 5.”

So Batman has a strength of 5 (roughly 8 times stronger than an average human), while Superman has a strength of 50 (roughly 18 trillion times stronger than Batman). The two of them can exist on the same scale without having stats that are so long they run off the page. Of course, that mind-boggling gap also points out some of the structural problems of the DCU in those days — many of its heroes were so staggeringly powerful that it was almost impossible to place them in dramatic jeopardy. DC would attempt to solve those problems with its Crisis On Infinite Earths, a universal reboot that set DC characters back to more reasonable power levels. In the 1989 second edition of the game, Superman’s strength was down to 25, a mere 16-million-fold increase over Batman. Well, a little more reasonable anyway.

Crisis was also a 1985 event, a 12-issue “maxi-series” that ran from April 1985 to March 1986. In fact, the DC Heroes RPG got released right in the middle of the series, which put Gorden in an awkward position. Mayfair couldn’t wait a year for the series to complete — they needed to get their game out in time for the ’85 Christmas season — but releasing before Crisis was over meant that some of the game’s information would be drastically wrong almost immediately. In fact, Gorden had to include a section in his (charming) designer’s notes entitled “What about Crisis On Infinite Earths?”, which explained that he was bound not to include details in the game that would spoil developments in Crisis, some of which DC hadn’t decided yet anyway! Nevertheless, he assured us that he’d been working extensively with DC editorial, and that “The information in the game, concerning characters and places and events, are compatible with my latest information as to how things will be when Crisis is over…” mostly.

The yearlong story arc of Crisis wasn’t the only thing making DC Heroes‘ timing awkward. It also came out just before two other epochal publications that would change the tone of comics for years to come: Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and another little series called Watchmen. Mayfair had followed up DC Heroes, as any good RPG publisher would, with a blizzard of supplements — adventure modules, sourcebooks, atlases, and so forth. How could they incorporate these radical new visions into the game’s generally sunny tone?

Well, Miller’s Batman was grizzled and futuristic, but he was still Batman, and could be addressed as a kind of “imaginary story” scenario. The Watchmen characters and their universe, though, were brand new, and would have to be statted up in new publications. Mayfair took three shots at this:

- Who Watches The Watchmen?, a 1987 module by Dan Greenberg — set in 1966 of Watchmen time,

- Taking Out The Trash, another 1987 module, this one by Ray Winninger and set in Watchmen‘s 1968, and finally the

- Watchmen Sourcebook, also by Winninger and containing loads of background information for the characters and their world.

In 2019, DC very helpfully — no doubt motivated by Watchmen‘s latest media juicing on HBO — collected all three of these artifacts into a volume they call the Watchmen Companion. (It also conveniently includes that issue of The Question that “guest-stars” Rorschach.)

The supplements have a fascinating history, especially considering the fact that Alan Moore actively collaborated with their authors. This was before his contract disputes with DC, and obviously well before his current vituperation of all things superheroic. Back in the Mayfair days, he was just another DC creator, excited about the possibilities of exploring his fictional universe. Dave Gibbons also participated, contributing original art to the modules.

It’s worth noting that Moore and Gibbons’ participation makes these RPG materials the only extensions of Watchmen ever created that could reasonably lay claim to any kind of “canonical” status. Greenberg rejects this notion, saying, “Only the Watchmen series itself is canon. My game is only an adaptation — reflected light and not the source.” Similarly, Winninger considers his work “a little footnote in the Watchmen story.”

Ultimately, I think the question of this material’s canonicity is kind of a silly one. Did these stories “really happen” in the Watchmen universe? Are they “really” part of the legend, or aren’t they? Well, does it matter? Would it change anything about the series if they are, or aren’t? As Moore writes in his script for the 1986 final issue of Superman Volume One, “This is an IMAGINARY STORY… aren’t they all?”

Who Plays The Watchmen?

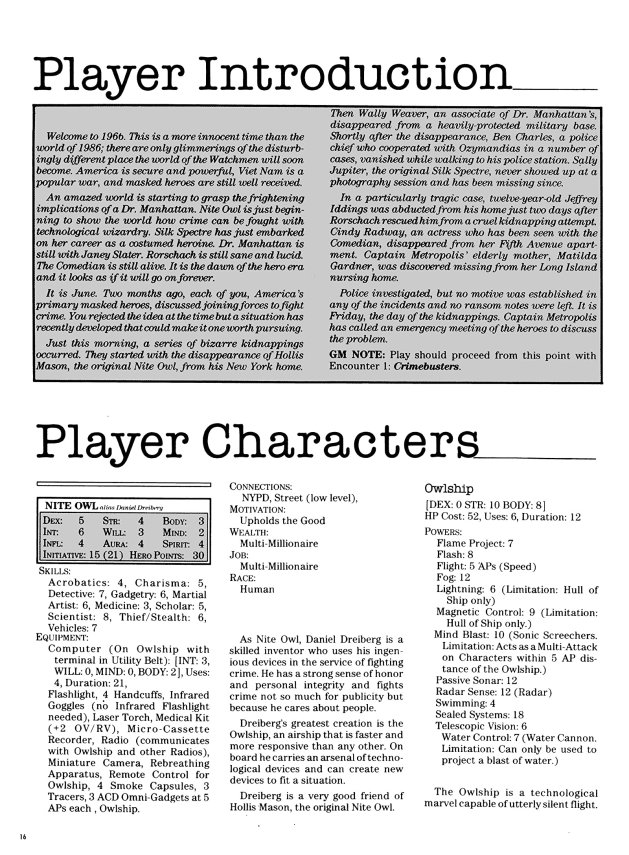

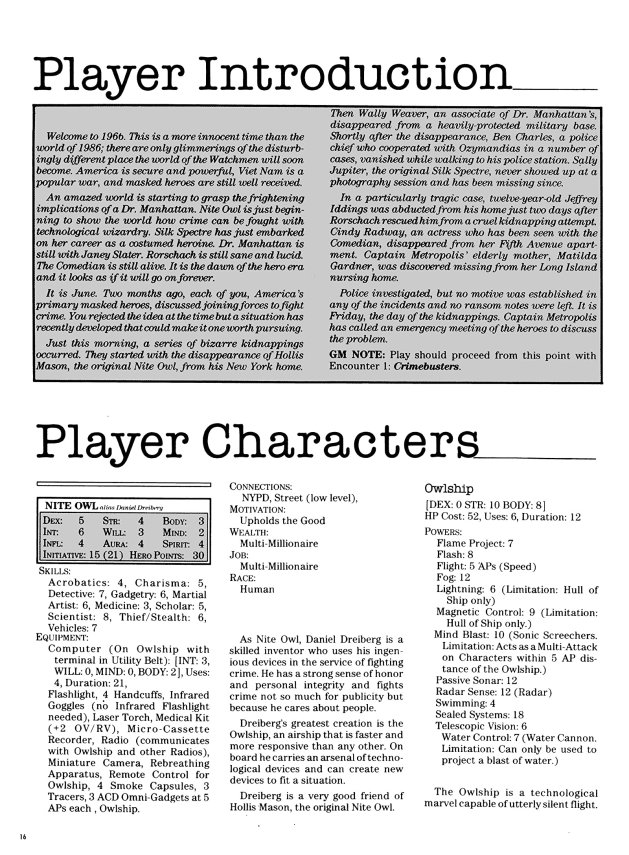

In any case, RPG modules aren’t really stories, but rather frameworks within which a variety of stories could take place. For Greenberg’s module, that meant exploring what might have happened after the failed attempt by Captain Metropolis (aka Nelson Gardner) to create the “Crimebusters” with the book’s six main characters in 1966. The module’s story picks up immediately after this meeting, with Nelly scheming a way to persuade the heroes over to his side.

Echoing the plot of Watchmen itself, Captain Metropolis decides that his would-be Crimebusters must have a common enemy to confront. He disguises himself as a mysterious underworld boss called only “M” (thus rather ingeniously linking not only himself and Moloch, but also two Fritz Lang references), and hires underworld goons to arrange kidnappings of people close to each of the characters, such as Hollis Mason, Sally Jupiter, and even his own mother, Matilda. Still more nefariously, Gardner ties the kidnappings to a civil rights group known as the American Negro Alliance, thus focusing superheroic attention on all that “black unrest” he was so worried about at the meeting.

He calls the heroes together, and asks them to work as a team to help find all the missing victims, since the kidnappings seem to have targeted the not-really-Crimebusters as a group. What happens next? Well, that’s up to the players. Interactive narratives can allow the story to travel down a number of different possible roads. Depending on the range of interactivity available, the story may be more or less “on rails”, but in a tabletop RPG, players are generally offered a very wide range of action. So maybe the characters look into the kidnappings, or maybe they look into why Captain Metropolis is the one to bring them together, or maybe they decide to write the whole thing off and go on patrol, or go to Antarctica, or go back home. Heck, maybe they’re homemade heroes who aren’t even the characters from Watchmen at all.

The module assumes that they are the Watchmen characters (though not Dr. Manhattan, it should be noted), and that they do decide to investigate the kidnappings. It’s up to a Gamemaster (GM) to decide how much to rein the players’ choices into what the module covers. Assuming they do decide to chase down the clues, how much they find depends on their ideas and their dice rolls.

If the players and their dice rolls cooperate with the story’s framework, and/or a GM engineers events such that players proceed through the module as written, they’re likely to visit the offices of the American Negro Alliance, the apartment of an underworld figure called “Mole”, and/or a counterculture rally in Battery Park. The GM is encouraged to play Captain Metropolis as uptight, whiny, and racist — challenging ANA workers for being “uppity”, or complaining at the rally, “That isn’t music! It’s noise! And to think they are playing on the same stand the Air Force Band and the Singing Sergeants play on every Fourth of July. There is no justice.” Even if the players don’t suspect him, they’re sure to dislike him.

Finally, they’ll be led to Moloch, who has indeed been funding more radical protest groups, since their activities draw the attention of the police, thus distracting the cops from Moloch himself. If defeated in battle, Moloch will (truthfully) deny any knowledge of the kidnappings, though, and Gardner will find a way to “discover” a note with information as to the whereabouts of the missing people. If the rescue goes well, the players may believe that Moloch was behind the whole thing. If it goes badly, Captain Metropolis may have to reveal his secret in order to keep his mother alive.

Do the heroes find out who’s been pulling their strings? Do they come together as the Crimebusters after all? Do they splinter again, no different than they were before the beginning of the module? How it goes will vary from one gaming group to the next, an ambiguous outcome which is not only in keeping with the spirit of RPGs, but of Watchmen itself. The last page of the game deliberately echoes the “I leave it entirely in your hands” last page of the book, in the section describing a confrontation with Gardner:

What the Players elect to do with Captain Metropolis is their matter. They could turn him over to the police, ostracize him from hero society, or they could view his act as a noble, if dangerous, one and consider maintaining their allegiances. The decision is theirs.

The Harlot’s Curse Taking Out The Trash

Winninger also cared very much about staying true to the spirit of Watchmen, a fact which shines through several different aspects of his module, Taking Out The Trash. For one thing, it tries to be just as atmospheric and reference-heavy as Watchmen itself. DC Heroes modules are broken up into “encounters” (scenes, more or less), and the title of every encounter in Taking Out The Trash references a pop song — “The Sound Of Silence”, “Sympathy For The Devil”, “I Am the Walrus”, and so forth. (Or at least, most of them do — I couldn’t find a clear referent for a couple.) Not only that, the GM is encouraged to open most scenes with either a snippet of Rorschach’s Journal or an excerpt from William Blake‘s poem “London”. One of the main antagonist groups scrawls graffiti everywhere that quotes from Blake’s Marriage of Heaven And Hell. A literary quote accompanies each main character’s stat block and history, pulling in authors like Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, and Sir Phillip Sidney. You get the picture.

The module also uses a similar storytelling technique to the back matter in Watchmen issues, providing exposition and background via newspaper clippings, interview excerpts, or “found” documents like a letter to Adrian Veidt from his head of marketing. With a smile and a wink, this letter purports to accompany “the manuscript the guy from Chicago turned in for the second adventure in the ‘Ozymandias Role Playing Game.'” Winninger, let it be noted, got the call to write this second Watchmen module while still a student at Northwestern.

That “manuscript” includes a historical breakdown of the Watchmen world, with a writing credit shared between Winninger and Moore. Now, based on everything Winninger has said about the process of creating these supplements, I don’t believe that means that Moore actually produced any of this module’s text at his own typewriter. Rather, I suspect that Winninger (and Mayfair) provided him a co-writing credit because this section of the module was a summary of the work Moore had already produced — with some extra details added here and there. This is different from the rest of the module, which was much more original to Winninger — the Blake-quoting street gang didn’t come from Moore.

In fact, that gang is an example of how the module’s references aren’t always handled with Moore’s grace — they often feel troweled in, or just tacked on. Then again, as Winninger notes in his introduction to The Watchmen Companion, he was all of 20 years old when he wrote the thing, so fair enough. The form and content of the entire adventure represent a bold grasp at the kind of ambition that marks Watchmen throughout. That includes the plot, which finds the main characters at the 1968 Republican convention, working to prevent Moloch from assassinating Richard Nixon, and (if they succeed) thereby ensuring the beginning of the Nixon presidency that continues all the way into Watchmen‘s 1985.

Or, at least, that’s what Winninger intended. Mayfair unfortunately took an editorial machete to Winninger’s manuscript, derailing much of its historicity. He tells it best:

Mayfair editorial excised all its references to real people and places and replaced most of them with goofy parodies. Oliver North became “Findlay Setchfield South.” Max’s Kansas City became “Mex’s Indy City,” home of the “Velour Underground.” Nixon is known only as “the VP,” confusing readers. (Hubert Humphrey was Vice President in 1968; Nixon was VP a full 10 years earlier.)… Worst of all, the book was hastily retitled “Taking Out The Trash.” My title, “The Harlot’s Curse,” was pulled from the William Blake poem that serves as an epigraph to the story, following the template Alan established in naming each of Watchmen‘s 12 chapters.

Now, in fairness to Mayfair, when your market is likely the parents of adolescent boys, having the word “harlot” in your title probably represents an unreasonable risk. Nevertheless, all of Mayfair’s changes do have a significant negative impact on the module, and signify the struggle that they had with incorporating Moore and Gibbons’ dark vision into their world of Teen Titans and Justice League. The “Velour Underground” and “Findlay Setchfield South” feel very mainstream DC, a bit like Metropolis and Hub City.

Mayfair editorial could have helped in the department of fact-checking and proofreading, but several prominent errors remain in the book. The overall plot summary (captioned “The Big Picture”) cuts off mid-sentence, about 70% of the way through. (This error wasn’t created by the The Watchmen Companion‘s reprint — it exists in the original module.) Rorschach gets called “Joseph Walter Kovacs”, when in fact his correct name is “Walter Joseph Kovacs.” The module refers to Hooded Justice throughout as “The Hooded Justice”, or sometimes just “The Justice.” Perhaps it’s a misnomer acquired via Eighties DC comics’ habit of saying “The Batman” rather than just “Batman”?

In any case, the story of the module follows the heroes’ discovery of a gang called the Bretheren (the Blake-obsessed criminals), who turn out to pose a threat to the convention, which in the Watchmen game universe takes place in New York rather than in Miami. An NYPD captain and a Secret Service honcho ask the heroes to provide security for the convention, and players can find a number of clues that help them track down the gang. After a climactic battle on the convention floor, successful players may discover that Moloch was directing the Bretheren’s attacks, in hopes that he could eliminate the competition for a candidate called Ken Shade, who had essentially “sold his soul” to Moloch’s organized crime network in order to pay gambling debts. They may also choose to take down the gang once and for all at its headquarters.

Strangely, there’s a subplot running through the module that involves only The Comedian. In these scenes, The Comedian follows “Findlay Setchfield South”‘s orders to eliminate a different rival to Nixon. I haven’t logged the world’s most RPG hours myself, but I’ve played my share, and the experience is almost always a group one. Having a GM play out a separate series of scenes with just one player, especially when those scenes are meant to be interleaved with the main action and kept secret from the other players, seems like it would require a pretty unusual gaming group dynamic. I wonder how many of the GMs who ran this module ended up just jettisoning the extra Comedian stuff entirely?

As always, there are plenty of ways for the story to end, depending on what directions the players chose and how well the dice cooperated with their intentions. In the module’s epilogue, which assumes that they’ve successfully foiled Moloch and The Bretheren, the characters watch on television as Nixon (or rather “The VP”) accepts his nomination, and then the GM reads out a final Blake quote, this one incorporating “the youthful Harlot’s Curse” and how it “blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.” Even in success, players get a very downbeat ending, in keeping with the mood of Watchmen itself.

Back To The Source

The third Mayfair Watchmen publication isn’t an adventure at all, but what the game calls a sourcebook. Here’s their explanation:

A sourcebook contains game-related and background material on a certain subject relating to the DC Universe, most often a specific group of heroes, a certain location, or a special genre. GMs who prefer writing their own adventures will find sourcebooks especially helpful, since in addition to characters’ statistics, sourcebooks contain historical, organizational, and reference material about the sourcebook’s subject.

By 1990, when this book was published, Mayfair had produced plenty of sourcebooks — Batman, Superman, Doom Patrol, Justice League, Apokolips, et cetera. These books tended to be detailed breakdowns of the characters in question, plus articles about their gear, their headquarters, their supporting casts and rogue’s galleries, and so on. The Watchmen sourcebook took a different tack.

Rather than just writing article after article about Watchmen characters, Winninger took a page from Moore’s book (often literally) and provided background in the spirit of Watchmen‘s back matter — newspaper clippings, correspondence, psychiatric reports, ID cards, excerpts from Under The Hood and so on. I say he literally took a page because maybe 25% of the sourcebook is reprints of Moore’s back matter itself, often reformatted or parceled out into different pieces, but otherwise intact.

Some of the new material reinforces the book’s story (such as a newspaper clipping whose headline reads “Nite Owl breaks Rorschach out of Riker’s Island!”), but much of it builds on tiny hints in the book. For instance, we get full stats and descriptions for every villain or joke-villain that even gets a whisper of a mention in Watchmen — Captain Axis, Underboss, The Twilight Lady, The Screaming Skull, and so on — with a brief origin story, a “whatever happened to” section, and even the most famous crime pulled by each. The book has a full writeup of the “Owlcar” that Dan and Laurie walk by in his basement, complete with budget and possible issues (“Standard Tires are woefully inadequate. Tires must be armored against damage.”) There’s a floor plan of Minutemen headquarters.

Winninger managed to throw in a few jokes himself. For instance, in the Rorschach section, we get a scrap of Rorschach’s journal proclaiming that he has “at least one ally here in the lair of the weak”: a taxi driver. It seems Rorschach was fleeing the police when a cab driver offered him a ride. “Told me I was his hero. Told me he was compelled to war against the sinners and the politicians and the false prophets as well.” Winninger’s insertion of Travis Bickle (obviously) into Rorschach’s backstory draws similar conclusions to what annotators would be arguing for in years to come.

He also took open questions from the text of Watchmen and closed them. For instance: who killed Ursula Zandt, the Silhouette? Hollis Mason in Watchmen only tells us that “she was murdered, along with her lover, by one of her former enemies.” Winninger names this enemy in Taking Out The Trash: it was apparently “the Liquidator.” The Sourcebook gives us a description of the Minutemen’s battle with this Liquidator, his hospital report after the battle (including his real name), and the section of her biography that details the murder scene.

In a similar fashion, Winninger nails down the identity of Hooded Justice, which brings us at long last to the Watchmen web annotations. In their endpages notes for Chapter 3, those annotations state:

Hooded Justice was likely killed by the Comedian. (If Mueller (sic) was Hooded Justice. There is no evidence for this anywhere in the comic; but the Mayfair Games DC Heroes Module, “Taking Out the Trash,” agrees with this assessment, in the section co-written by Moore.)

This note resolving Hooded Justice’s identity is ironic when it annotates a page where Hollis Mason writes, “Real life is messy, inconsistent, and it’s seldom when anything ever really gets resolved.” Mayfair’s Watchmen materials are messy at times, but they’re pretty consistent, and at least when it comes to the sourcebook, they resolve a lot. Hooded Justice’s section of that book has immigration documents for Müller’s parents, police reports of their domestic violence cases, a note from Rolf’s father leaving his mother, ads from his circus strongman career, newspaper clippings, the New Frontiersman smear on him, and more.

It’s wonderful stuff, full of story hooks for enterprising GMs, but from today’s vantage point, at least for someone who’s watched the Watchmen HBO series, its neat resolutions have acquired some competition. I couldn’t help reading all the Rolf Müller stuff with a sense of disappointment, because while that take on the Hooded Justice story is fine, I found Damon Lindelof’s alternate origin of Hooded Justice as Will Reeves to be orders of magnitude more compelling. Perhaps it’s because the Watchmen sourcebook is an invitation to creativity, but the HBO series is an outpouring of creativity, a response to Watchmen‘s questions that, like the original, constructs a crystalline and multi-layered story that works on a myriad of levels.

It’s difficult, maybe impossible, for an interactive narrative to meet that standard, and that’s one of the fundamental problems with trying to make any aspect of Watchmen interactive. The book is a self-contained universe, a precision timepiece whose pieces fit together exquisitely, allowing for no deviation. Where all the other DC books (with the possible exception of The Dark Knight Returns) just go on and on and on, Watchmen has a very clear stopping point, after which most of the characters are either erased or so radically changed that they’re basically starting from scratch.

Consequently, when Mayfair wanted to create interactive experiences in the Watchmen universe, they had to go back into the past — 1966 or 1968 in their two attempts. Of course, because Watchmen is only 12 issues, and only part of those detail the past, there’s not a large menu of options to choose from — hence both modules’ reliance on Moloch as a villain. Similarly, the sourcebook pours a lot of effort into detailing character histories, but by the time Watchmen ends, most of those histories have ended permanently. To play through any scenario that matters with them, you’d have to go back into the past.

That’s what made Lindelof’s choice to go forward instead such a brilliant one. He was able to still make use of some of the book’s characters, but he accepted the challenge of starting anew. Could Angela Abar’s story play out in an RPG? I can’t say it’s impossible, because there’s a world full of creativity out there, but I think it’s fair to say that the structures of the story inherently resist interactivity, because the way they travel through time, the way they reveal themselves gradually, and the sense of inevitability around them, is just too precise.

Doctor Manhattan personifies this inevitability, which is why he’s quickly written out of both modules. Well, that’s not quite true. Greenberg’s module allows for the possibility that Dr. Manhattan could be a player character, one with knowledge of Captain Metropolis’ plan, but cautions:

It is vital, however, that the Player not act on this information and confront Captain Metropolis because, in his timeline, Dr. Manhattan did not confront Captain Metropolis in the past, is not confronting Captain Metropolis in the present, and will not confront him in the future. Dr. Manhattan is tied to his timeline, and while he knows the future, he cannot alter it.

But in this case, really, what’s the point of role-playing? Not only that, unlike the Dr. Manhattan of the text, it’s completely impossible for an RPG Manhattan to see all eras simultaneously, because he’s not in a text. In a book or show where every narrative turn is already worked out, such a character is like someone who’s already read or watched the whole thing. But an RPG is tied to time far differently – not even the GM knows how things will work out.

I would argue that Watchmen inherently resists expansion, and all the projects that have tried have all had to find ways to escape the original’s gravity. I haven’t explored them all, and I don’t plan to, but reading Mayfair’s material makes it clear to me that another self-contained dramatic effort has a much greater chance of success than an open-ended interactive one. RPGs, like William Burroughs’ cut-ups, explore the way randomness can drive narrative, but Watchmen leaves nothing to chance.

Next Entry: Time Pieces

Previous entry: Triangolo des Vigilantes

[Acknowledgements: In preparation for writing this post, I watched Vincent Florio’s video explanations of the DC Heroes game, lurked on the DC Heroes facebook group, listened to the Hero Points Podcast, and checked out the All-Star Games show on DC Universe. All of these resources were extremely useful for helping me understand the game as it’s played, and I’m grateful to everyone who had a hand in their creation!]