Spoilery essays are my game

I spoil without cessation

Watchmen and Moore, and Bester for sure

For this post’s entire duration

SPOILERS AHEAD for Watchmen and for many works of Alfred Bester, particularly The Stars My Destination. I also spoil the overall arc of The Count of Monte Cristo.

Sometimes I swear these web annotations are just free-associating. Take this comment, about the “Here be tygers” panel I discussed in the first Blake post:

Given Moore’s allusions-within-allusions, I wonder if the Rorschach=Tyger material is also a back-door reference to Alfred Bester’s Tyger, Tyger!, a.k.a The Stars My Destination, with its terribly flawed protagonist Gully Foyle and the telepathically ignited super-explosive pYre. Foyle also has time-and-space teleportational adventures like Dr. Manhattan.

I’m not sure what’s meant by “allusions-within-allusions”, unless we’re talking about an allusion to something that itself is an allusion to something else. If that’s the case, I think the annotator has it backwards. If Moore had referenced the Bester book in Watchmen, then we could see Blake inside that reference, given that the UK title of The Stars My Destination was Tiger! Tiger! (with an “i”, not a “y”), and it uses Blake’s “The Tyger” as an epigraph for its first section. Instead, I think there’s no encapsulation — both works just reference Blake, like a whole bunch of other works do.

However, the entire premise of this project is that Watchmen exists in a complex intertextual web, enabled by Moore and Gibbons’s considerable cultural erudition, allowing this comic book superhero story to touch Greek myth, The Bible, ancient Rome, rock and roll songs, and all sorts of points in between. The free-associating annotations have led us down some blind alleys before, and even those trips found something worthwhile, so there’s likely plenty of value in checking out the connections between Bester and Watchmen whether or not Moore was aware of The Stars My Destination.

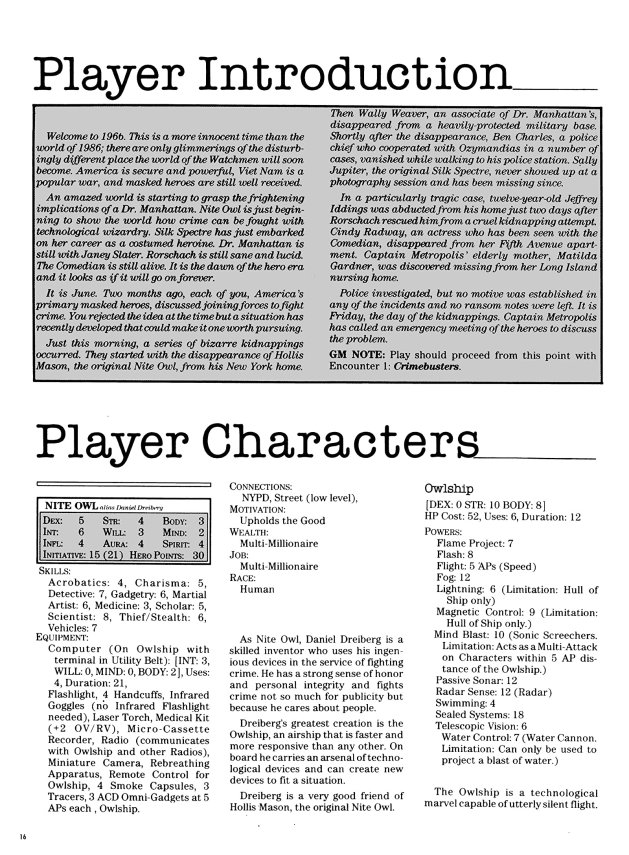

Lucky for us, this is one awareness we don’t have to guess at, because it turns out that Moore directly referenced the novel in an earlier work. Starting in 1980, Moore (under the pen name “Curt Vile”) wrote and drew a comic series for Sounds, a UK music weekly, and the name of that comic was The Stars My Degradation. Lest we think this was just a silly riff on something he’d seen on a bookshelf, Moore includes an element in every strip to let us know he’s a little more familiar with the book than that.

See, at the beginning of Bester’s novel, our protagonist (the aforementioned Gully Foyle) finds himself stranded in the destroyed spaceship Nomad, barely eking out an existence for one hundred seventy days and counting. In this state, “occasionally his raveling mind leaped backward thirty years to his childhood and remembered a nursery jingle:”

Gully Foyle is my name

And Terra is my nation.

Deep space is my dwelling place

And death’s my destination

(The Stars My Destination, pg. 11)

This variation on an identifying book rhyme recurs like a leitmotif through the story, and you will probably not be surprised to learn that by the end, it finishes with “the stars my destination.” Moore’s work, on the other hand, carries the following rhyme in its weekly title masthead:

Dempster Dingbunger is my name

Sputwang is my nation

The depths of space gob in my face

The stars my degradation

So, yeah, the tone here is very different — intentionally zany and a little gross. The comic strip doesn’t really pertain much to Bester’s work or to Moore’s subsequent career, but at least it establishes that Moore would definitely have been familiar with TSMD by the time he was writing Watchmen.

Inoculation Via Fixation

With that connection firmly established, let’s move on to examining The Stars My Destination, in search of lights to shine on Watchmen. We know that Gully Foyle starts the book stranded in the Nomad, struggling to stay alive, so what happens next?

A ship appears! It’s the Vorga, seemingly ready to save Foyle’s life, and he sends up distress flares that the ship can’t miss, but despite his obvious need for rescue, the Vorga sails on by. He is abandoned once more. At this point, Foyle’s desperate drive to survive becomes a burning need for revenge, which consumes him so completely that he becomes capable of amazing feats in pursuit of that goal.

He rescues himself from the shattered starship. He escapes an asteroid colony of bizarre primitives, but not before they tattoo his face in a tiger pattern (hence the UK title and epigraph.) He makes his way back to Earth and gathers resources to find the ship in its dock and attempt to destroy it. The attempt fails and he is captured, but his captors also fail in their attempts at interrogation. They are interested in finding the Nomad, but no method of questioning can pierce Gully’s monomania — he exists only to destroy the Vorga.

So he is sent to a deep underground prison in France, called the Gouffre Martel. The French connection is apropos, because here the novel moves into a long riff on The Count of Monte Cristo. Like Edmond Dantès, Foyle finds a friend in prison, who educates him and helps him to escape. Like Dantès, Foyle becomes impossibly wealthy, and uses this wealth to assume a different identity, carrying out elaborate plans for revenge upon those who wronged him. In doing so, he evolves from a dangerous brute into an even more dangerous trickster.

Foyle’s story up to this point resonates strongly with two Watchmen characters: Rorschach and Ozymandias. Gully the brute, who takes up the first 30% or so of the book, is very much like Rorschach — resourceful and violent — and once he gets tattooed, he also has patterns on his face like Rorschach.

There’s a scene during his interrogation where the questioners have set up an elaborate ruse to make Gully think that his actual identity is that of the uber-wealthy Geoffrey Fourmyle, and that his life as simple spaceman Foyle was an escapist dream. His questioners know, though he doesn’t, that the Nomad had valuable and important cargo, so they want to trick him into revealing its location. “Reconstruct this false memory of yours in detail,” says the questioner, “and I will tear it down.” (pg. 56-57) Foyle wavers for a moment, then catches sight of his reflection in the questioner’s spectacles. The sight of his tiger-patterned face returns him to himself, and he overcomes the false narrative.

Just so, Rorschach finds himself trapped and questioned in prison, called by a name he rejects. He has been stripped of what he considers his face, but Malcolm Long keeps putting Rorschach blots in front of him. Those blots, rather than helping him create a path to the “healthy” identity to which Long wants to lead him, continue to bring him back to himself as Rorschach, because to him, those blots are his face. Just as Foyle sees his stripes in his adversary’s glasses, Rorschach keeps being shown his own reflection.

Foyle eventually gets surgery to conceal the stripes, and his tormentors are worried they won’t be able to recognize him. “We’ve never seen his face…” they say, “only the mask.” (pg. 94) This too is like Rorschach, who considers the mask his real face, and who can move through the city unidentified once he removes it.

The two characters resonate through their external patterning, but their deeper kinship is their shared single-mindedness. As Foyle is tortured, this time with nightmarish images of hell and monsters, he just keeps repeating, “Vorga. Vorga. Vorga.” The book’s omniscient narrator steps back for moment to comment on him, saying, “He had been inoculated by his own fixation. His own nightmare had rendered him immune.” (pg. 54) Rorschach, too, has been branded by his trauma, and it has turned him into a fixated machine, devoted only to his own goals, even in the face of Armageddon.

Foyle’s interrogator inadvertently reveals that the Nomad was carrying an enormous fortune in platinum bullion, and the moment Foyle hears this, his obsession has a new focus. He sees that money as “a broad highway to Vorga” (pg. 59), and from that moment, he is determined to recover it. And he does! He escapes from prison, makes his way back to Nomad, obtains its cargo, eludes his pursuers, and returns to Earth with limitless wealth.

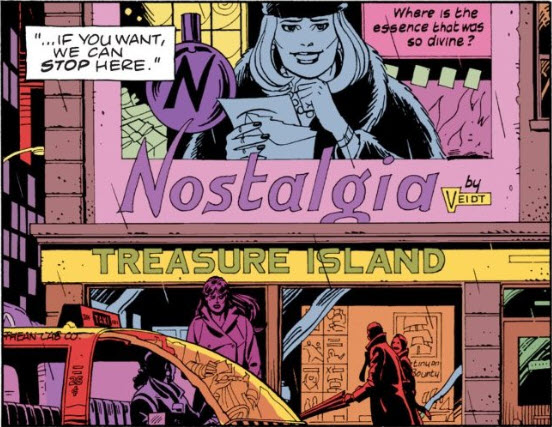

With these resources in hand, Foyle goes full Count of Monte Cristo, or in Watchmen terms, full Ozymandias. He actually adopts the identity of Geoffrey Fourmyle of Ceres, “a wealthy young buffoon from the largest of the asteroids.” (pg. 111) With his Four Mile Circus, he travels around to various places causing delightful chaos, dazzling the locals. But what he’s really doing is setting elaborate plans in motion, in service of his revenge.

He’s moved beyond the notion of destroying the Vorga itself, realizing that it is simply a physical object, Instead, he hunts down the crew who were on the ship the day it abandoned him, ceaselessly searching for the reason why they left him alone, and for the most part unbothered by any conscience in how he seeks that information. He also becomes an “extraordinary fighting machine” (pg. 115) like Ozymandias, but rather than undertaking intense training, Foyle simply buys himself a suite of cybernetic physical enhancements, which allow him to increase his strength and speed to superhuman proportions.

Here is Foyle after these changes: a devastating fighter, possessed of unbelievable resources, who makes plans lasting months and years to achieve his ultimate goal. He’s a lot like a superhero, except that he is no hero — he’s perfectly willing to torture and kill in order to get what he wants. Sound familiar? Geoffrey Fourmyle is to Ozymandias as the initial Gully Foyle is to Rorschach, and that draws an interesting line between the two Watchmen characters.

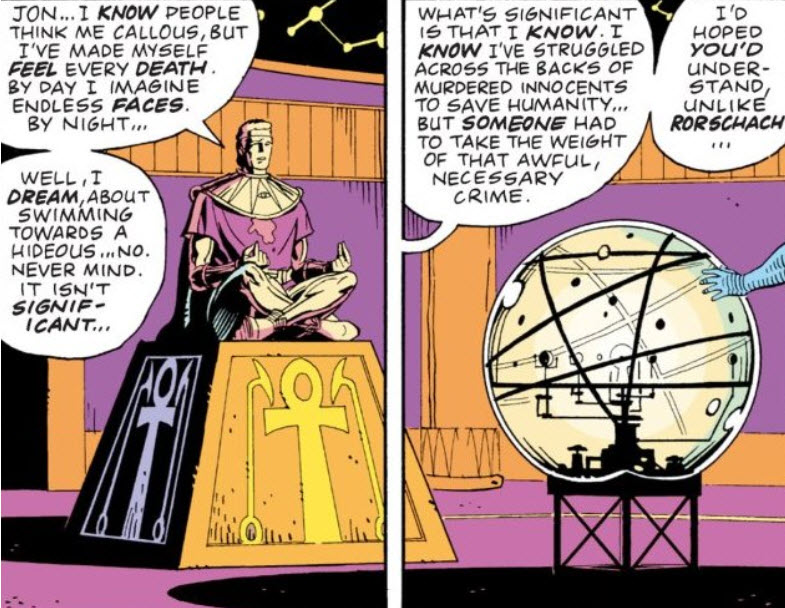

Veidt and Kovacs, alone among the book’s cast, are the two who cannot and will not be swayed by anything. Dan is diffident, Laurie reluctant, Jon indifferent, and Blake mercenary, but Ozymandias and Rorschach are monomaniacs, relentlessly pursuing their own goals and stopping at nothing. A character says to Foyle, “You can’t accept life as it is. You refuse. You attack it… try to force it into your own pattern.” These words could as aptly describe Rorschach, railing in his journal at the city’s filth and corruption, or Ozymandias, authoring his own apocalypse to resolve the unbearable tension between the world as it is and the world as he wishes it to be.

Yet there is one more stage for Foyle, beyond his Rorschach phase and beyond his Ozymandias phase. He falls desperately in love with a blind girl named Olivia, only to discover later that she was in fact the captain of the Vorga that day, and that the ship passed him by because it was in the midst of a despicable criminal operation: picking up desperate refugees from war-torn planets, collecting their belongings, and ejecting the people into space. She is an utter nihilist, driven by pure hatred to ravage and destroy all of humanity. She sees in Foyle someone who is just as powerful and — she thinks — just as amoral, and falls in love with him too, wanting him to join her in her campaign of ruination.

Gully kisses her, and then he recoils. She says:

‘What is it, Gully darling?’

‘I’m not a child any more,’ he said wearily. ‘I’ve learned to understand that nothing is simple. There’s never a simple answer. You can love someone and loathe them.’

‘Can you, Gully?’

‘And you’re making me loathe myself.’

‘No, my dear’

‘I’ve been a tiger all my life. I trained myself… educated myself… pulled myself up by my stripes to make me a stronger tiger with a longer claw and a sharper tooth… quick and deadly…’

‘And you are. You are. The deadliest.’

‘No, I’m not. I went too far. I went beyond simplicity. I turned myself into a thinking creature. I look through your blind eyes, my love whom I loathe, and I see myself. The tiger’s gone.’ (pg. 195)

This is the moment when Foyle transcends his idée fixe, transcends his Rorschach and Ozymandias personas, and leaves childhood behind. He acknowledges that there’s never a simple answer. Adrian Veidt, by contrast, sneers at Dan, “Do grow up,” but he’s scarcely less of a child than Rorschach. His prank on the world, as complex as it was to engineer, remains an attempt at a quick fix, a simple answer. He deludes himself that he has engineered a happy ending, only to be reminded that nothing ever ends.

The application of violence or trickery to exert control over the world has a fundamental quality of tantrum, and thus of monstrosity — a force beyond rationality and beyond compassion. In Watchmen, Moore subtly suggests that this childish fantasy sits behind all superhero narratives. In The Stars My Destination, Foyle sees these qualities in himself, and chooses to leave them behind. Rather than hoard and hide the most destructive power in the universe (the pYre explosive mentioned in the web annotations), in the belief that he knows better how to apply it, he instead distributes it across the spectrum of humanity.

Will they destroy themselves with it? Possibly! But Foyle rejects the argument that people must be controlled, again deploying the imagery of adulthood and childhood. “Stop treating them like children and they’ll stop behaving like children,” he says. “Let ’em all grow up. It’s about time.” (pg. 235) Where Ozymandias would use secrets and lies to guide the mass of humans where he thinks they should go, Foyle opts for radical truth, and radical faith: “I believe in them. I was one of them before I turned tiger. They can all turn uncommon if they’re kicked awake like I was.” (pg. 236)

What leads him there is the moment he sees himself in Olivia, and realizes that he loathes what he sees. In that moment, he is faced with fundamental questions: How can we move through this world without loathing ourselves? How can we find our way out of monstrosity? No one in Watchmen ever asks these questions. “This relentless world,” muses Rorschach. “There is only one sane response to it.” But what? To Rorschach, the answer is, “Become just as relentless.” But Foyle, and Bester through him, shows us another way: allow the world to be itself, speak and live the truth, reject the simple answer, and lift up your fellow creatures where you can.

Maturation Via Irritation

Rejection of the simple answer, and demolition of hoary clichés, were hallmarks of Bester’s career. As he made his way into the field in the early 1940s, Bester quickly began taking aim at science fiction tropes that even by then had become entrenched, such as the “Adam and Eve” story. In case that doesn’t ring a bell, it’s a story about some kind of apocalypse or post-apocalypse in which only two people remain, and it turns out those two people are named — dun-dun-DUNNNN! — Adam and Eve. Or some variation thereupon. Or they may not even have the heavy-handed names, but nevertheless are called upon to repopulate the world, which often turns out to have been Earth All Along.

Bester roasted this trope in a couple of 1941 stories. “The Biped, Reegan” is told from the viewpoint of an ant, who misunderstands the humans it watches — the story depends on our knowledge of the cliché to understand what’s happening, treating it as a joke rather than a portentous twist ending. “Adam and No Eve” goes even further, with the last man finding himself alone on a ruined earth, no Eve in sight. Eventually he gets himself to the ocean and dies, at which point — the story strongly implies — his decomposing body will provide the raw materials in a primordial soup that leads to our own existence, a hundred million centuries later. With this stroke, Bester both points up the absurdity of the Adam-and-Eve plot (you don’t get a healthy and genetically diverse population from a starting point of two organisms) and twists it into something genuinely surprising.

In later stories, he went on to skewer other SF shibboleths — Asimov’s laws of robotics in “Fondly Fahrenheit”, the notion of predictive psychology (also Asimov) in “The Push of a Finger”, time-travel power fantasies in “The Men Who Murdered Mohammed” and “Of Time and Third Avenue”, and so on. TSMD itself is a pointed denunciation of the “one man to save the world” trope common in the works of Heinlein and others — and for that matter, superhero comics. In fact, Bester did work at DC Comics for some time, tutored by Batman co-creator Bill Finger. Some of Bester’s DC comics creations and co-creations have had a lasting impact, such as Solomon Grundy, Vandal Savage, and most famously the Green Lantern oath (“In brightest day, in blackest night”, etc.)

In any case, in his campaign to jolt SF from its adolescent moorings, he even published essays having a go at the notion that science fiction was growing up, such as his famously combative “The Trematode: A Critique of Modern Science-Fiction” in 1953, in which he outlined what he saw as SF’s “Three Immaturities” — intellectual, emotional, and technical. Literary critic Jad Smith explains the title:

A trematode infests a mollusk and either spoils it or forces it to produce a pearl. From Bester’s standpoint, only time would tell whether SF would yield a lustrous gem or turn to rot, succumbing to what he personally saw as its own self-incurred immaturity. He had his doubts but, for his part, hoped for the pearl. (Alfred Bester, pg. 11)

The parallel to Alan Moore is clear. Like Bester, Moore came into his field with a healthy contempt for the ossified concepts that had become ritualized in the superhero genre, even those that were wildly popular at the time — we can see a great example of this in his parody of the X-Men around the middle of The Stars My Degradation. Much of his work wasn’t so goofy, though. He savagely dismantled a “Shazam!” style hero in Miracleman, (literally) took apart and rebuilt Swamp Thing, and interrogated the fundamental concept of costumed violence against the status quo in V For Vendetta, along with an incredible abundance of other superhero and science fiction stories in the five years following Degradation, all leading up to the magnum opus of Watchmen.

I’ve mentioned before that Moore saw the DC heroes as one-dimensional and the Marvel heroes as two-dimensional. Watchmen was the pinnacle of his project to add a third dimension to superheroes, and to critique the entire genre. But why did he make this his project in the first place? Perhaps, like Bester, he wanted to be the irritant inside the oyster of a genre, hoping for a pearl.

Moore, like Bob Dylan before him, and Alfred Bester before that, was engaged in a quest for redemption. These artists sought to take the forms and tropes that spoke to them as children and make them meaningful to adults. Bester addressed this aim directly in a plot outline he sent to the editors of Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine for his story, “5,271,009”:

I want to preach a sermon (as usual) in this story, and the theme is an attack on the adolescent wish-fulfillment-type dreaming which blocks us from becoming adults if we indulge it wihtout recognizing it for what it is. It is this same adolescent wish-fulfillment which science fiction so shamelessly exploits; and if SF continues to indulge it, SF will never become an adult form of literature. (pg. 126)

There is it is again, that metaphor of adult vs. child. The same imagery crops up in the story itself, in which the supernatural being Solon Aquila takes a protagonist through a variety of wish-fulfillment scenarios, all of which were familiar tropes from SF of the time, all of which are fatally flawed in ways the protagonist discovers, escaping the scenario whenever he finds the flaw. Finally, Aquila reveals that he has been trying to forcibly mature the character, by showing him the shallowness of “baby dreams”, in an attempt to prompt “adult dreams.”

The March 1954 issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction, featuring Bester’s story “5,271,009”

What to make of all this focus on growing up? I would speculate that Bester, and artists like him, seek to mature their art forms as a way of maturing themselves, but without losing the fundamental qualities of childhood that so enraptured them to the art form in the first place. In doing so, they create art that speaks to all of us who are ambivalent about the socially inscribed lines between childhood and adulthood, who seek to integrate the younger parts of ourselves with the older parts.

Unlike Moore and Dylan in their fields, Bester did not have a lasting and fruitful career in SF. He created two universally acclaimed novels, TSMD and The Demolished Man, which won the very first Hugo award. He’s also remembered for a handful of classic short stories, of which I’ve mentioned several. But he drifted in and out of the field, and when he returned to it once more late in life, his work didn’t captivate SF audiences anymore.

Fascination via Saturation

In his monograph on Bester, Jad Smith brings in a concept from literary theorist Roland Barthes, of the “writable text” — “writable” implying a level of reader engagement beyond simply “readable”. Smith summarizes the concept, taken from Barthes’ S/Z, as a kind of surfeit of meanings, possibilities, and connections within a text that holds both danger and promise for the reader’s experience. Writers in this style are

not only consciously fostering a certain level of meaningful indeterminacy in a text but also engaging in a kind of knowing parry-and-thrust with readers’ expectations for a particular genre. This excess within the text was a risk for the writer — it recognized the reader as a free and individual agent in resolving narrative ambiguities — but it also served as a possible source of heightened pleasure for that very reason. (pg. 14)

Smith argues convincingly throughout his book that Bester’s greatest works derive much of their greatness from this “writable” quality, and it seems to me that this is a very useful concept for Watchmen as well, not to mention much of Moore’s work, such as the incredibly oversaturated League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series.

I would argue that Watchmen fulfills this concept of a “writable” text in a few ways. Certainly the “knowing parry-and-thrust with readers’ expectations for a particular genre” is all over the book, starting with the fact that it’s a DC comic that doesn’t use any of the established DC characters. Add to that the ways that the Watchmen characters darkly reflect their Charlton counterparts, with whom some segment of the readership would have been familiar.

On top of these points of engagement, or of “meaningful indeterminacy”, there are all the ways in which Moore contravenes established superhero narrative expectations, from the fact that superheroes are illegal in the story’s world, to the fact that they are incredibly flawed, broken human beings who behave in anti-heroic or outright villainous ways, to the fact that good, arguably, does not triumph in the end. In fact, pure good and evil don’t really show up in the story at all — just a bunch of moral gray spaces whose rightness is always up for debate.

In addition to all this, let’s consider that Moore mixes the mystery genre into the superhero genre, and that mysteries themselves are among the most “writable” works, consciously involving the reader in a puzzle to be solved, in the resolution of narrative ambiguities. However, though we do find out in the end who killed The Comedian, Watchmen doesn’t resolve like a traditional mystery, with the clever detective piecing the clues together and bringing the killer to justice. Instead, our detectives are overpowered by the killer, who then explains his crime and how, by his lights, it and its attached scheme have just saved all of humanity. “How… how can humans make decisions like this?” sputters one stymied would-be crimebuster.

Even at this, we as readers are not done exercising our agency to solve narrative ambiguities, as the ending of the story lands on a series of very fragile notes, culminating in its final words: “I leave it entirely in your hands.” Diegetically, that remark is addressed to Seymour (who may, in fact, be on the precipice of “seeing more”), but in a larger sense, it is addressed to us as readers, who must determine in our own imaginations what happens next.

There is yet another dimension to writability, according to Smith, and that is the aspect of narrative saturation. Many of Bester’s works were heavily engaged with not only the science fiction tropes of their day, but a much larger domain of literature, such as TSMD‘s conscious evocation of Blake, Dumas, Joyce, and plenty more antecedents. Take a look at Smith’s explanation of Bester’s cultural pastiche in the story “Hell Is Forever”, and see if it doesn’t ring any bells:

He playfully referenced and appropriated various texts to create a saturated intertext, one open to more than just one reading protocol. A reader need not get all the allusions or understand how Bester’s approach takes in elements of decadent and modernist aesthetics to enjoy the story or even to feel the effect of narrative oversaturation, but this other level of meaning does produce writable moments capable of enhancing a reader’s experience of the text.

Yeah, that’s Watchmen all over, and I’ve been working to unearth those moments for the last 12+ years. Every time I dive into one of these references and appropriations, trying to crystallize a bit of precipitate from Moore and Gibbons’ heavy saturation, it opens new avenues of pleasure available from the text. This is true even when the connection seems weak, down to outright free-association, and the fact that Watchmen continues to reward such close and varied analysis, from dozens of different directions, places it unambiguously on the highest shelves of literature.

Previous entry: Bringing Light to the World