First things first: this project has a new name. I was never entirely satisfied with The Annotated Annotated Watchmen as a project title. Not only is it an awkward mouthful, it’s factually inaccurate. I’m writing essays, not annotations. But The Essayed Watchmen never really did it for me either.

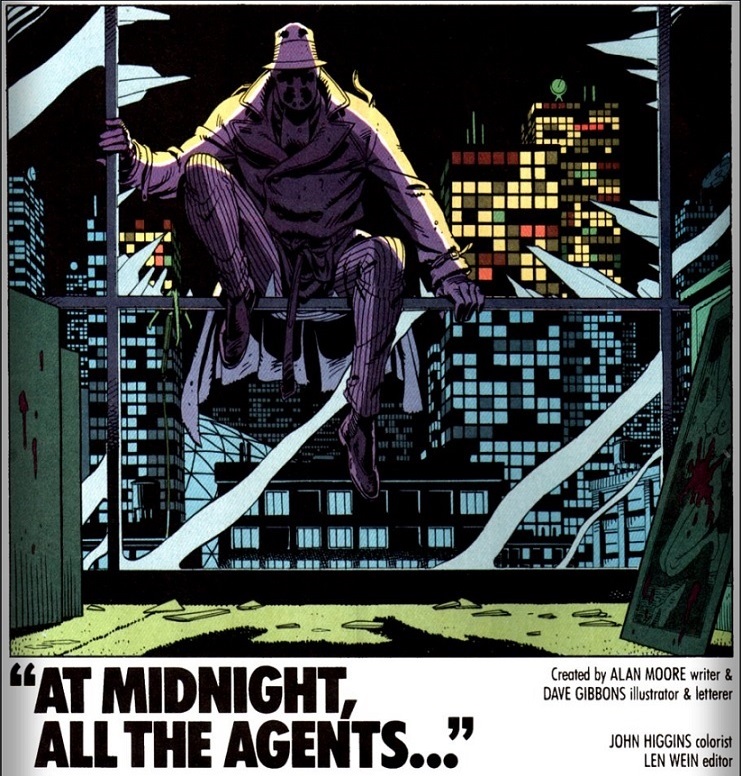

For many an entry have I fretted about this, but I just could not find an alternate title that spoke to me loudly and clearly enough. For this 25th post, though, I resolved to redouble my efforts, and in a reread of Chapter 1 noticed this panel:

The bestiary! In Watchmen, the bestiary seems to be two things. First, it’s a collection of items that underpin the universe, which Dr. Manhattan examines in order to better understand the workings of that universe. So far, so perfect — that’s exactly what these essays are working to do, one exotic and breathtaking specimen at a time. The other Bestiary in Watchmen is “where the real heavy-duty thinkin’ gets done” by the Gila Flats crew in Jon Osterman’s early days as a physicist. It’s the on-base bar where the various residents find themselves “at play amidst the strangeness and charm.”

That meaning works perfectly for me too, because these essays are my way of extending the tremendous strangeness and charm that Watchmen exerts over me and millions of other readers. And doing so is just plain fun for me, which is why I keep doing it. It sure isn’t for the money or fame.

Therefore, I proudly present The Watchmen Bestiary, a rechristening of my ongoing Watchmen project. As a part of this change, I’ve gone back in and renamed all the old entries, and in some cases done some light editing and updating of them. If anyone happens across anything screwed up as a result of this, please let me know.

And now, on with today’s entry. Please note that, as always, there are Watchmen spoilers in this post. I also discuss the plot of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis.

Most of these essays focus on a single work, or at least the works of a single artist or author. Today’s entry, though, focuses on a name. It’s a name that spans many works, many authors. A name that echoes through millennia. Moloch.

Here’s what Chapter 2 of the web annotations has to say about him:

Moloch, an ancient god who became a demon in Christian cosmology, is also the name given to the giant machine with a giant dial operated by the oppressed workers in Fritz Lang’s film “Metropolis”.

The annotations are quite right to cite the Bible and Metropolis, as both were pretty clearly influences on Moore. He references the Bible throughout Watchmen — the Pale Horse reference to Revelation is just the first of many.

The Metropolis connection is a bit more tenuous, but apart from being able to count on Moore’s general erudition, there’s also the fact that both Metropolis and Lang’s recurring character Dr. Mabuse feature prominently in the League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen story Nemo: The Roses Of Berlin. Granted, that book came out much later than Watchmen, but let’s also remember that in 1984, music producer Giorgio Moroder restored and re-released Lang’s film in theaters, with a pop music soundtrack. Between the fact that the pop Metropolis was roughly contemporary during the writing of Watchmen, and Moore’s later demonstrated connection to the material, I’m comfortable asserting that Metropolis would have been in Moore’s constellation of references when he chose to name a character Moloch.

Also in that constellation are the writers of the Beat movement. We’ve already seen how strong an influence William Burroughs had on Watchmen, but it turns out he wasn’t the only Beat with a connection. As it happens, Allen Ginsberg’s most famous poem, “Howl”, repeats the word “Moloch” 39 times in the 383 words of its second section, employing imagery that was clearly influenced by Lang. There are plenty of other writers who incorporate Moloch — Milton and Flaubert are a couple of the biggies — but it’s the Bible, Metropolis, and “Howl” that seem most connected with Moore’s repertoire, so let’s focus on them.

Moloch The Abomination

In the Bible, Moloch or Molech (both spellings appear in the King James Version) seems to derive from the Hebrew word melech, meaning “king”, combined with the vowels from the word for “shame” to give it a pejorative flavor. The implication is of a “Lord” (or god) whose worshipers should be ashamed.

Most of the mentions of Moloch occur in Leviticus, a book concerned with setting out rules for the Israelites. A typical mention, as translated in the KJV: “And thou shalt not let any of thy seed pass through the fire to Molech, neither shalt thou profane the name of thy god: I am the LORD.” (Lev 18:21) This diction may obscure just what’s being forbidden, but the English Standard Version is as usual more straightforward: “You shall not give any of your children to offer them to Molech, and so profane the name of your God: I am the LORD.” In 1 Kings he is called an “abomination”, and we see Solomon seduced into worshiping him. (1 Kings 11:7)

So it would appear that Moloch is a rival god to Yahweh, and that Moloch’s distinguishing feature is his demand that followers sacrifice their children to him, likely by ritual burning if the oft-repeated phrase “pass through the fire” has any literal meaning at all. In fact, a couple of 19th-century German scholars offered the radical argument that the cult of Yahweh in fact grew out of the cult of Moloch, differentiating itself by its rejection of human sacrifice. Other critics saw anti-Semitism in this premise, an attempt to slander Jews by suggesting that the “orthodox” version of Judaism was entwined in blood rituals. For our purposes, what matters is that the Biblical Moloch is synonymous with human sacrifice, in particular the sacrifice of children, and that this practice sets him apart from Yahweh.

What does this idea of human sacrifice have to do with Watchmen‘s Moloch? Very little, I would argue. Edgar Jacobi, aka Moloch, who Hollis Mason describes as “an ingenious and flamboyant criminal mastermind” in his heyday, seems to be Watchmen‘s canonical example of the “schmuck in a Halloween suit” that the Comedian derides in one of this chapter’s flashbacks. He’s non-threatening enough that Veidt’s marketing department eventually wants to make an action figure out of him.

There is almost no hint of human sacrifice, nor indeed any kind of murder, in what we know about him. He initially styles himself as a stage magician, and tends to sport a tuxedo in the flashbacks to his active days. In Chapter 4 we see him with a spooky skull necklace, but that’s about as close as he gets to courting death. He appropriates the name (and perhaps the pointy ears?) of a demon-god, but does nothing very demonic or godlike, moving into organized crime in the 1940s before finally spending the Seventies in jail.

So why the name Moloch? What does the concept of Moloch have to do with anything in Watchmen? Well, the actual Edgar Jacobi may be a red herring, the literal example of false danger that The Comedian cites in the Crimebusters meeting, but there is indeed a figure who embodies all that Moloch represents: Ozymandias. Adrian Veidt fancies himself somewhere between a king and a god. In the Bible, the difference between good god Yahweh and wicked god Moloch is whether that god is willing to sacrifice its own. Yahweh doesn’t demand the killing of anyone’s children. (Well, except for that one time, and it turns out He was faking it.) Ozymandias, though, creates an entire plan predicated on human sacrifice, and not just any humans, but the very New Yorkers whom he protected in his days as a costumed hero.

Even before the book’s climactic slaughter, Adrian is methodically killing people all over the place. He blows up the boat containing all the writers, artists, and scientists he bribed and tricked into his scheme. He eliminates every underworld figure who could be traced back to Pyramid Deliveries. He irradiates Dr. Manhattan’s associates to give them cancer, thus making Watchmen‘s Moloch the subject rather than the object of sacrifice. All in the service of his vision.

When comparing Watchmen to the book of Revelation, we saw how much Moore and Gibbons’ story was an inversion of the Biblical apocalypse, from its disruption of the good/evil binary to its reversal of the typical combat myth. In Ozymandias, we see yet another Biblical reversal — rather than Yahweh’s rejection of child sacrifice, Ozymandias turns into the kind of god who embraces it. The closest thing to a child character in the book — Bernard the younger — dies in the arms of his elder namesake when Veidt’s squid creature arrives.

The Moloch Machine

Adrian also has a few things in common with Joh Fredersen, the master of the title Metropolis in Fritz Lang’s film. Both men are masters of a business empire, who have attendants hanging on their every word to carry out their orders. Where Veidt built the Antarctic refuge of Karnak and its fantastical vivarium, Fredersen created the “Stadium Of The Sons”, in which the male offspring of Metropolis’s 1% frolic among freely available plants, fountains, and women. Where Veidt registered the patent for spark hydrants thanks to possibilities opened up by Dr. Manhattan, Fredersen creates a dazzling city thanks to the inventions of archetypal mad scientist Carl Rotwang. And where Nite Owl and Rorschach uncover the horrific human cost that Veidt is willing to incur in order to realize his dream, in Metropolis it’s Joh’s son Freder who makes the sickening discovery.

One day, as Freder is having his usual grand time in the Stadium Of The Sons, his merriment is interrupted by a working-class woman named Maria, who has taken a group of children up to the stadium to see how the upper crust lives. He becomes obsessed with Maria, and tries to follow her down to the underside of Metropolis, where workers endure endless toil to keep all the city’s machines operating. As viewers, we’ve already witnessed scenes of exhausted workers trooping through the undercity, their lives ruled by an omnipresent clock — another symbol in common between Metropolis and Watchmen.

When Freder enters the undercity, one of the first sights he encounters is an enormous machine, with rows of workers pulling levers in steady rhythm to keep its mysterious energies flowing. As Freder watches in alarm, one enervated worker struggles to do his part, but falls short, and the mechanism’s temperature rises. Finally, the thermometer reaches a critical level, and an explosion rocks the machine, sending workers flying through the air. At this moment, Freder has a vision of the machine as a huge, terrifying demon that consumes workers alive. Shaved and chained, they trudge up the stairs to be thrown into the fires within its gaping mouth. Overcome by the vision, Freder shouts out one word: “MOLOCH!”

There’s not much ambiguity about the symbolic weight of this Moloch machine, nor in fact most of Metropolis, which takes its cue from the novel of the same name written by Lang’s then-wife Thea Von Harbou. The film announces in its first title card, “The mediator between brain and hands must be the heart!”, and then goes on to make it clear that the brain is capital (i.e. Joh) and the hands are the proletariat (i.e. those devoured by the Moloch machine.) In Joh Fredersen’s Metropolis, the price of that beautiful stadium, and the debauched club Yoshiwara, and all the other amazing conveyances and edifices and inventions, is human sacrifice. Working class people struggle and die to keep the machines fed, and when those machines go explosively wrong, the ruling class sees it as an impersonal correction, just one of those things.

When it seems like the “hands” might revolt, under the leadership of Maria, Fredersen and Rotwang disguise an android with her appearance, so as to disrupt the rebellion by discrediting its figurehead. Disaster ensues, culminating in a rooftop swordfight between Rotwang and Freder, who finally triumphs, killing the mad scientist. The film’s rather naive ending solves the problem of the city’s cruel machinery when Freder (as the mediating heart) joins the hands of capitalist Fredersen and lead worker Grot.

Ozymandias, too, builds an enormous machine to fuel his fondest dreams, but in his case the machine isn’t made of dials and levers and gears. It’s made of plans, and it consumes people for its purposes with no mediating heart in sight. Like the machines of Metropolis, it also reaches deep under the surface. According to this chapter, Veidt formed his intention in 1966 to solve the problem of inevitable nuclear war. According to Doug Roth in Chapter 4, Wally Weaver died of cancer in 1971. That means that Veidt’s plan was in motion within at least 5 years of that Crimebusters meeting, and that its turning gears had claimed their first life by then. In the ensuing 14 years, it finally realizes its destiny as “a lethal pyramid”, killing everyone involved, excepting some but not all of our main characters. After the hordes of corpses in chapter 12, Rorschach is the final slave to be marched into the gaping maw of Adrian’s Moloch machine.

It isn’t just planning, though. Veidt also relies upon a remarkable technology stack to create his “practical joke,” one even more farfetched than the androids and mega-machines of Metropolis. He kills his servants by elaborately staging their “deaths from exposure, after drunkenly opening [his] vivarium.” Like much of Metropolis, it makes for a hell of a visual, but falters under a bit of scrutiny — why would a tropical vivarium in Antarctica ever need to open in such a way, anyway? When Dan expresses skepticism that Adrian is even capable of killing half of New York, Veidt calmly explains that he cloned the brain of a psychic named Robert Deschaines into a “resonator”, with “terrible information” coded into it. Then, when its host creature dies, this mega-psychic brain somehow broadcasts “the signal triggered by the onset of death”, and that signal somehow kills 3 million people from “the shock”.

I think of Watchmen as a realistically grounded superhero narrative, maybe the most realistic one ever at the time of its publication. If you can accept the notion of Dr. Manhattan and how his existence would change the world, the rest plays out logically with no further recourse to the supernatural, right? Well, wrong. Because as wide-ranging as Dr. Manhattan’s powers and effects may be, they don’t reasonably explain the presence of psychic abilities in human beings. Veidt gestures to advancements in eugenics as Laurie fawns over Bubastis in Chapter 4, but telepathy is another story. Because Watchmen drapes itself in superhero tropes, it’s easy to overlook, but for Veidt’s plan to work, we must accept not only the implications of Dr. Manhattan, but the entirely separate implications of people who can project their thoughts.

Besides sharing in its implausibility, Ozymandias also echoes Metropolis by wielding super-scientific advancements as a murder weapon against anyone opposing his utopia. Despite his Egyptian iconography, Adrian Veidt is a technologist who achieves his victories through a combination of commerce and machines, using flesh draped on a bomb like the false Maria in Metropolis.

Moloch Whose Fingers Are Ten Armies

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.

He invokes “Moloch” like a chant in section II of the poem, and some of the imagery recalls Metropolis pretty clearly:

Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies! Moloch whose breast is a cannibal dynamo! Moloch whose ear is a smoking tomb!

Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows! Moloch whose skyscrapers stand in the long streets like endless Jehovahs! Moloch whose factories dream and croak in the fog! Moloch whose smoke-stacks and antennae crown the cities!

The second quoted stanza clearly identifies various parts of the city as Moloch, and a Metropolis-like city it is, with skyscrapers, factories, smokestacks, and antennae. The anthropomorphization of buildings and tombs into body parts of the monster strongly echoes the way that the panels, apertures, and pipes of the Metropolis machine become eyes, mouth, and claws in Freder’s vision of Moloch. And of course the “cannibal dynamo” of its breast is pretty much a straight description of what happens in the Metropolis Moloch scene.

There may be another allusion to Lang here as well. One of the director’s trademarks was having a shot of a hand in each of his films, one way or another. Rotwang has an artificial hand that gets some attention, but there’s another sort of hand shot in the movie as well. There’s a sequence where Maria tells an allegorical story about building a “Tower of Babel”, another example of planning brains heartlessly directing working “hands”, and one famous shot from that sequence is of five columns of workers converging into a foreground of shave-pated men sullenly trudging forward.

As Tom Gunning points out in The Films Of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity, the shot strongly suggests a hand. “The shape itself acts as a trope, based on the synecdoche introduced in Harbou’s text, the workers as ‘hands.’ We see the converging columns as the outspread fingers and the circular insert as a palm. The composition of roiling bodies also functions as a symbolic close-up of a hand, one of Lang’s most powerful visual tropes.” Separate regiments of workers coalesce into one central force. Or, if you’re Allen Ginsberg, “Moloch whose fingers are ten armies!”

So if the Biblical Moloch demands human sacrifices, like Adrian, and the Metropolis Moloch uses humans as fuel, like Adrian’s plan, what does Ginsberg’s work add to our understanding? Simply this: that those sacrifices aren’t just anonymous workers or unnamed children, but characters we come to know and care about through the course of the story. In section I of “Howl,” Ginsberg introduces us to a litany of behaviors and characters who embody them. Most of these are of the heroic-romantic nature, albeit from a bohemian point of view, fugitives from mass culture who bravely maintained intellectual independence and created unfettered works. They are all destroyed, and it is Moloch who destroys them.

In Watchmen, we come to know some of the “ordinary” people who get killed on November 2, 1985. There’s Bernard the newsstand vendor and Bernard the young reader, who we hear from throughout the book. There’s Malcolm Long and his wife Gloria, stars of Chapter 6. There’s Joey and her girlfriend, who we see in the throes of painful relationship dissolution. There’s Detective Steve Fine and his partner Joe, who open Chapter 1 and continue to investigate crimes on the fringes throughout the story. Ozymandias is the Moloch to whom all these victims are sacrificed, to appease his thirst for surreptitious control of the world’s nations.

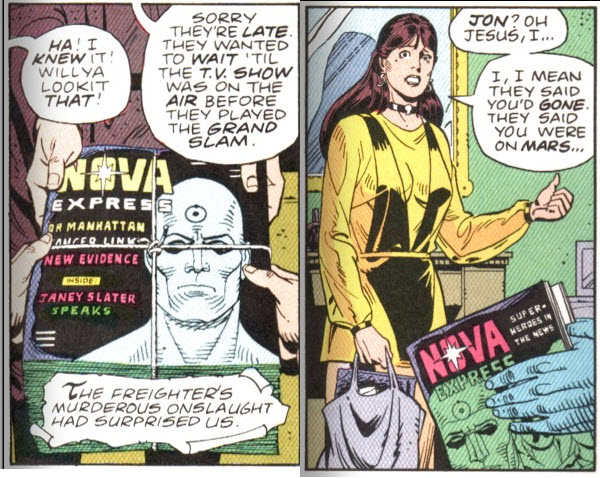

That day is the final step in Adrian’s homicidal plan, and a trail of death leads up to it. There’s the island full of artists, writers, and scientists — Max Shea, Hira Manish, James Trafford March, Linette Paley, Norman Leith, Dr. Whittaker Furnesse. The best minds of their generation, destroyed in Veidt’s madness. Not to mention the literal “best mind”, Robert Deschaines, who apparently was more than a “so-called psychic and clairvoyant.” And Wally Weaver, and Janey Slater, and poor Edgar Jacobi himself, all marched into the maw of Ozymandias’ Moloch machinations, feeding their energies into its terrible purpose.

The sad, cancerous old man pinned to the ground by Rorschach did none of these things. In fact, he was just another victim of them. Jacobi pleads, “I’m not Moloch anymore,” and he’s right. The new Moloch is Ozymandias himself, whose mind is pure machinery.

Next Entry: Tears Of A Clown

Previous Entry: How The Ghost Of You Clings

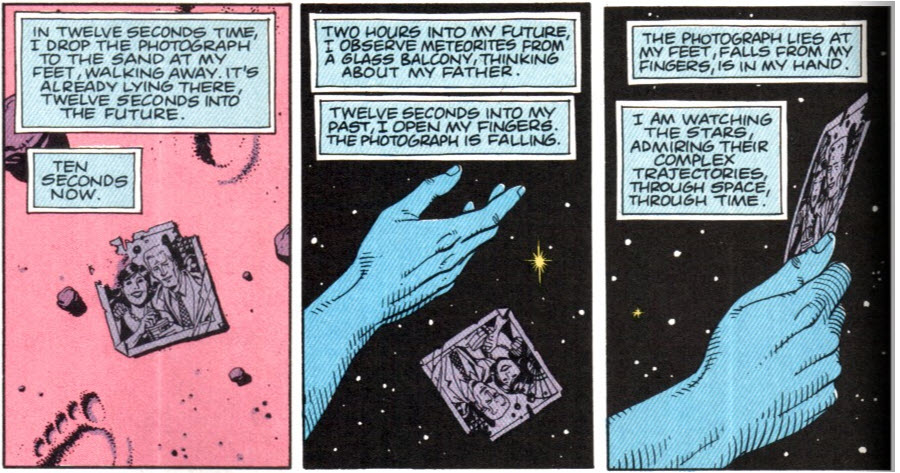

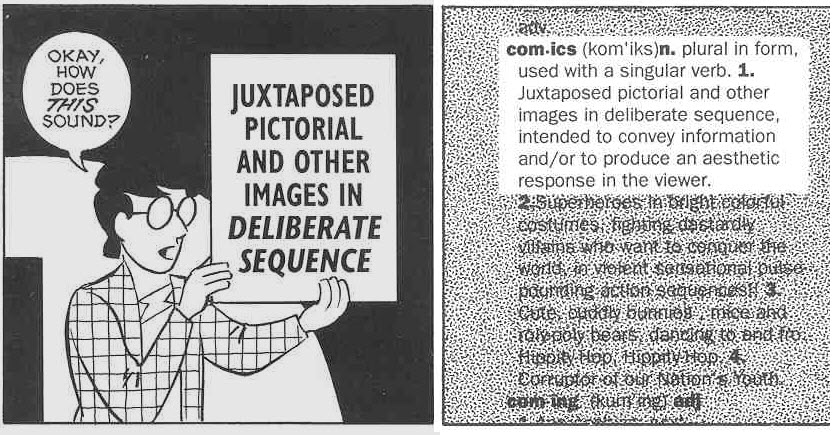

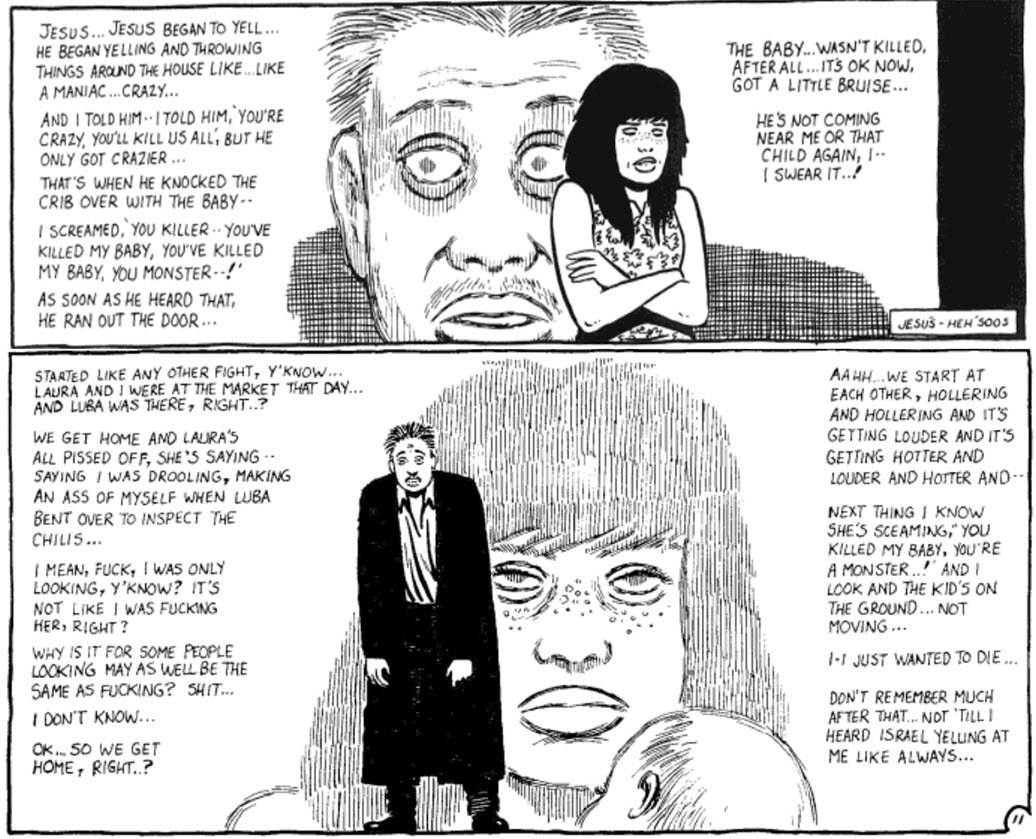

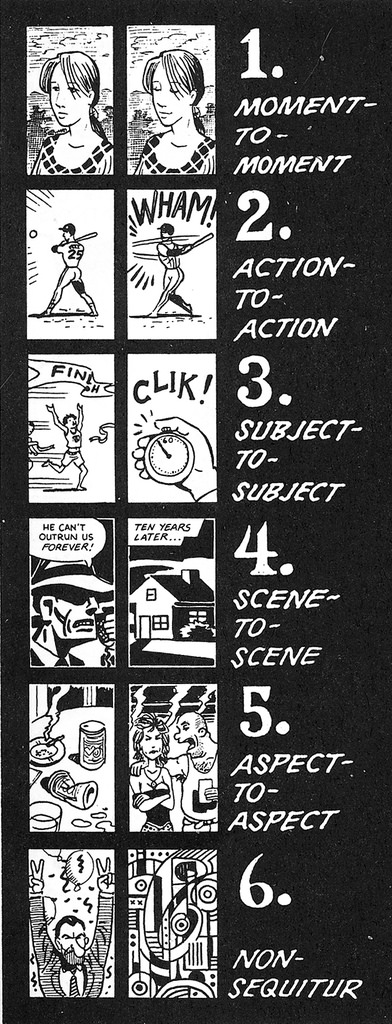

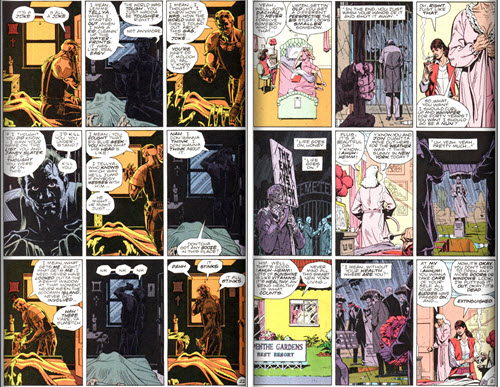

As we’ve learned, juxtaposition leads to association, and Watchmen exploits those associations to create a number of effects, like the time travel I discussed above, the

As we’ve learned, juxtaposition leads to association, and Watchmen exploits those associations to create a number of effects, like the time travel I discussed above, the