Abandon all hope of avoiding Watchmen spoilers, ye who read this post.

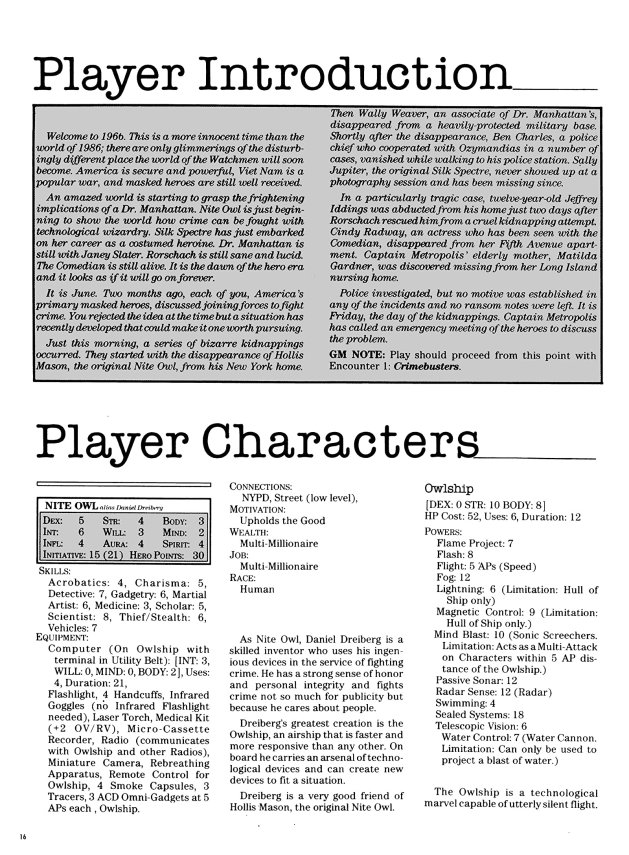

Our journey through Watchmen references has now crossed into Chapter 4, a chapter devoted exclusively to exploring the character and memories of Jon Osterman, Doctor Manhattan. One of those memories contains the next reference — from his early foray into superheroing:

The eagle-eyed Annotated Watchmen v2.0 finds a reference here that even Leslie Klinger missed, looking behind the caption box to notice:

The name of this “crime-den” is “Dante’s,” a reference to the Italian author best known for the Divine Comedy, which included a trip to Hell. The name and red lighting seem to be intended to invoke a hellish atmosphere.

Aside from the fact that the writer likely meant “evoke” rather than “invoke”, and that “vice-den” is improperly quoted as “crime-den”, this is an astute observation! The club name is mostly obscured, but once we see it as “Dante’s”, we can’t possibly see it as anything else, and indeed Dante’s version of Hell is underground, just as Moloch’s vice-den is said to be. The connection is very clear.

Dante and the Commedia

So let’s dive a bit into Dante and his greatest work. Dante Alighieri was born in 13th-century Florence, Italy. His birth year is widely accepted as 1265, though the logic behind establishing this birth year is, as Mark Scarbrough points out in his stellar podcast Walking With Dante, pretty specious. But it’s enough for our purposes to know that he was born midway through the 13th century, became active in Florentine politics as an adult, and was exiled in 1302 as the political terrain shifted. He died in 1321, having never returned to his home.

Dante had been writing and releasing poetry since well before the turn of the century, but it was in exile that he composed his master work, a work he simply called Comedy — “Commedia” in his medieval Tuscan. (The “Divine” would be added by his fan and commentator Boccaccio, well after Dante’s death. It’s also worth pointing out that the name “Comedy” isn’t after our modern sense of hilarity, but the older sense of a happy ending.) Comedy was a trip through the known universe, as Dante understood and imagined it, and it was also a comprehensive catalog of his moral and philosophical thought, deeply rooted in the Christianity (specifically Catholicism) of his time.

Dante composed his poem of individual cantos (think chapters or sections) grouped into three canticles: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. It’s written in the first person voice, and claims to be an account of how Dante became lost in a dark wood, and with help from the ghost of the classical poet Virgil, traversed every level of Hell (Inferno) and Purgatory (Purgatorio). He must leave Virgil behind to travel through Heaven (Paradiso), so Beatrice — his idealized woman and the object of his courtly love poems, who had died in 1290 — becomes his guide for the final piece of the trilogy.

Comedy makes a number of surprising literary moves, not least the way that it mixes together figures from disparate parts of both literature, religion, history, and local politics. In his travels, Dante the pilgrim meets characters from the Bible standing alongside men, women, and creatures from mythology. People from history and Dante’s own Florentine contemporaries populate the mix as well, so that the landscape of God’s judgment includes everyone who ever was or ever was imagined.

From our modern perspective, mixtures like this may not be too startling — we’ve seen Bill and Ted joshing with Socrates and Joan of Arc, or a Marvel comics universe where Thor and Hercules (and seemingly all the members of every other pantheon) run around with futuristic scientists and soldiers. For that matter, we’ve got Watchmen, in which we get The Comedian shaking hands with Gerald Ford and Doctor Manhattan with JFK. But in the 13th century, religion, myth, history, and current events didn’t mix in fiction — until Dante.

In addition to its bold approach to bricolage, Comedy also displays an astonishing level of structure. Medieval numerology is everywhere, peppering the work with threes, nines, tens and hundreds, among other sacred numbers. Three, being the holy number of the Trinity, appears at the highest level of abstraction — three parts of the Comedy itself — down to the lowest level of the poetic lines, which are written in a form called terza rima, in which rhymes repeat and interlock three times each. Nine, being three times three, is holy times holy, which is why we see nine circles of Hell, nine spheres of heaven, and so forth. Thirty-three is also a big one, with two of the canticles containing 33 cantos each, and most stanzas containing thirty-three syllables. (Dante would love the fact that this post is entry number 33 in the Watchmen Bestiary.)

Ten appears various places in the Bible, such as the Ten Commandments or the ten plagues of Egypt. Similarly, tens show up in the Comedy as well, such as when we add the “vestibules” to the nine levels of Hell and Heaven. Ten times ten — a perfect number in Dante’s sight — was the number of overall cantos in Comedy, and in fact that hundred is made of three thirty-threes plus an introductory one. (Inferno has 34 cantos.) This formulation of 9+1 or 99+1 undergirds the Comedy‘s structure, but there’s more to it than just numbers. Structure appears thematically, such as in Inferno, where Dante the pilgrim often echoes the sin he sees punished, and linguistically, such as the fact that each canticle of Comedy ends with the word “stelle” — stars.

In this way, Comedy resonates with Watchmen, which is itself richly structured. Moore and Gibbons aren’t so concerned with numbers, though Dante would doubtless appreciate the nine-panel layout employed throughout the book. With Watchmen, structure becomes more a matter of rhythm, such as the way that (for most of the book) plot-driven chapters alternate with character-driven chapters, or the way that changes in scene or lighting can create “X” and “O” shapes on the page.

Structure also shows up on the chapter level. In the Love & Rockets post, I went on at length about the structure of Chapter 2 — a present-day storyline interspersed with flashbacks, progressing in chronological order, with each showing The Comedian from a different character’s viewpoint. Probably the most famous structural trick in Watchmen occurs in Chapter 5, “Fearful Symmetry”, in which the panel layout for the entire issue is completely symmetrical, meeting in the middle with a double-page splash of Adrian Veidt fighting his would-be assassin. (Adrian, appropriately, is at the center of the story.) Symmetry appears in Comedy as well, with the mountain of Purgatory reflecting the cavern of Hell, and Purgatory itself poised midway through Dante’s journey, its middle cantos discussing the questions of free will that underpin the entire moral and theological structure of the poem.

The plots of the two works are quite different, of course. Watchmen operates (on the surface level anyway) as a mystery, while Comedy is essentially a tour — a very long tour through all the levels of a highly structured afterlife. That afterlife is divided according to sins and virtues, with each division populated by emblematic examples of the behavior — Judas as the ultimate traitor, Midas as the icon of avarice, and so on.

That said, Chapter 1 of Watchmen does take us on a tour, with Rorschach as our pilgrim and his own paranoia acting as his guide. As we follow, he takes us to each circle of “superhero” existence in his world, circles which encompass a number of solid archetypes. There’s the rough Comedian, grizzled and dark like a Punisher or Nick Fury. There’s the earnest Nite Owl and his cave full of gadgets and vehicles a la Batman. Ozymandias embodies the wealthy altruist — again Batman, but also Iron Man, Green Arrow, and many others — as well as the perfected human athlete such as Captain America or, uh… Batman. Silk Spectre comes across as the sex-bomb gymnast type, like Black Canary or Black Widow, while Dr. Manhattan has both the super-science of a Mr. Fantastic and the godlike power of a Superman. Thus our introduction to Watchmen takes us through a Dante-esque journey of figures exemplifying ideas, but the book holds their fates until its final chapter.

Manhattan and Morality

About those fates — one aspect of the moral structure that pervades the Inferno (and to a lesser extent Purgatorio) is the notion of contrapasso, which we may define more or less as “the punishment fitting the crime.” Thus usurers must carry a purse around their necks as they avoid fire raining from the sky. Soothsayers who tried to predict the future spend their time in Hell with their necks twisted 180 degrees, so they are only able to look backward. Flatterers are, well, immersed in shit. And so forth.

Watchmen doesn’t portray an afterlife of just desserts, but it does endeavor to show a variety of human (and superhuman) natures and their consequences, with no shortage of poetic justice, or at least poetic irony. Thus The Comedian, who lives his life as a fallen hero, becomes a truly fallen hero at his life’s end. Thus Nite Owl, who can only really feel like himself behind a mask, ends up adopting a whole new identity at the story’s end. Thus Ozymandias, whose name evokes Shelley’s poem about a king whose works were far less lasting than he belived they would be, creates a peace so fragile that a diary can tip it over. Thus Rorschach becomes a blot on a featureless white surface.

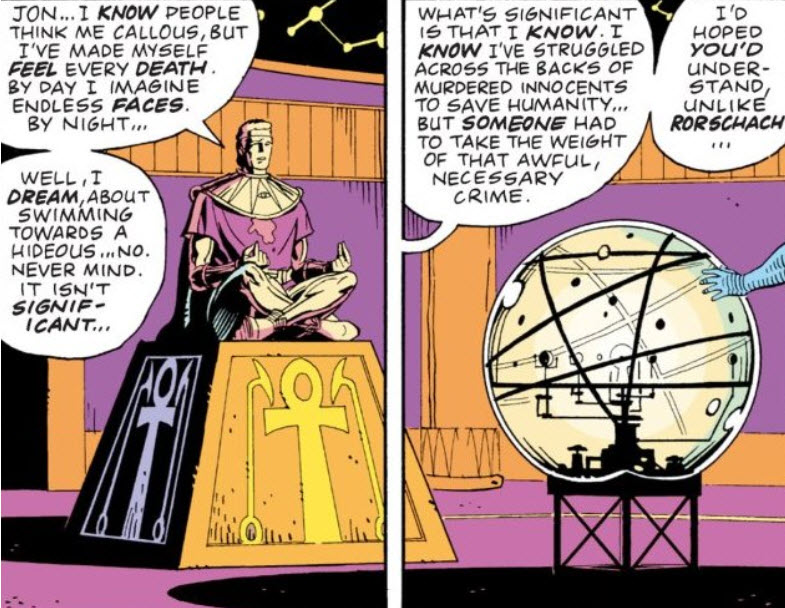

And what of Doctor Manhattan, the character whose chapter gets the Dante reference? Here we see some of the widest gaps between Comedy and Watchmen. Dante’s entire project is to flesh out a moral universe overseen by a stern and loving God, whose limitless knowledge pairs with a vast array of punishments, rewards, and (in the case of Purgatorio) one that can lead to the other. The closest thing to God in Watchmen‘s universe, though, is Doctor Manhattan himself, and the transformed Jon Osterman has very little interest in engaging with humanity at all, let alone constructing an afterlife of individual contrapasso for each member of it. The moral universe of Watchmen, as I discussed in the Bible reference posts, inverts traditional Christian stories to become a parody of their viewpoints.

Thus Doctor Manhattan’s story ends with him deciding to become God, and having observed him through the course of Watchmen, we might justifiably have our doubts about the sort of universe he will create. Where Dante’s God has love, Manhattan has only curiosity, and a rather weary curiosity at that. But there’s even more to this question of creators and the moral dimensions of their creations.

Consider this: Dante presents Comedy as the exploration of an afterlife created by God. But is it that, really? Of course not. It is the exploration of an afterlife created by Dante. And to make things even more complicated, Dante the creator poet explores his creation via the viewpoint of a pilgrim… who is also Dante. These two — the poet and the pilgrim — claim the same identity, but they are clearly not the same. Dante the pilgrim is a fictional character, entirely controlled by Dante the poet, who was a real person.

Moore and Gibbons don’t insert themselves into their story, but they do create a world that opens thorny questions about the nature of authorship. In the last entry, I asked whether Jon Osterman might have collapsed the probability waveform of his universe at the moment he became Doctor Manhattan, thus creating the future of his world at the moment he observed it. Maybe, maybe not, but the story does make very clear that at least he can see that future. More than that, as Chapter 4 shows, he lives it in all in the same moment, inhabiting a bewildering consciousness of mixed simultaneity and linearity.

He is, he tells us, a puppet who can see the strings. But he clearly can’t see all of them, because he remains unaware of his creators: Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. He is a sort of stand-in for the reader (or at least, the repeat reader) in his awareness of the full story, but even aside from not knowing the authors of it, there are other dimensions of his story that he fails to understand. In the panel that inspired this post, his voiceover states, “the morality of my activities escapes me,” as we see him exploding a gunman’s head. Let’s unpack that a little.

In the context of the story Dr. Manhattan is telling us, he’s been placed at that moment into a dubiously moral framework by the newspapers calling him a “crimefighter”, and the government insisting he live up to the label. So he might be saying that despite the entities claiming otherwise, he fails to see the morality of what he’s been sent out to do. As readers, we might agree with him there. But as is so often the case in Watchmen, the juxtaposition of words and pictures strikes a heavily ironic note — in this case, we’re watching the “crimefighter” casually murder a human who poses no threat to him. (No humans pose any threat to him, no matter how heavily armed.) The rest of the crowd, whatever their other vices, is shocked and horrified at this sight. Yet the immorality of Dr. Manhattan’s activities escapes him as well.

But it doesn’t escape us, and it doesn’t escape Moore and Gibbons. In that moment, they are clearly showing us the distance between Manhattan’s moral compass and their own, and presumably ours as well. So while Manhattan may be able to see the strings, that doesn’t mean he understands them. He is a compromised reader, and a compromised author. Why is he this way? I would suggest that, like Dante, Jon Osterman is an exile, and like Dante, the experience of exile fundamentally shapes his consciousness.

Osterman in Exile

In fact, Jon suffers a series of exiles, several of which we see in this chapter. In 1945, his father reacts to the news of Hiroshima by throwing away Jon’s cogs, in effect exiling him from his childhood identity as an aspiring watchmaker. From there, he is ejected from his childhood home, first to Princeton and then to Gila Flats. At that lab, inside the intrinsic field chamber, he suffers an exile far more profound: permanent estrangement from his own body.

There’s a section of the Inferno where Dante (the pilgrim) encounters the fate of suicides. The contrapasso for these souls, who shed their bodies voluntarily, is that they are forever denied those bodies in the afterlife. They are transformed into strange trees and bushes, gnarled and devoid of leaves. In this form, they can see other humans only as menaces — breakers of branches. After he constitutes an artificial body for himself, Jon Osterman finds himself similarly distanced from humanity, watching and participating in its activities with diminishing interest.

Finally, in the course of the book, he chooses to exile himself from humanity altogether, first to Mars, and then (we presume) much further by the story’s end. Perhaps in a sense this series of exiles echoes the progression of Comedy. Where at first Jon finds his expulsion from the life he imagined hellish, he seems to experience the removal of his body as purgatorial, a purgation of self, albeit an involuntary one. His final exiles out into space echo the images of the Paradiso, which was a journey through the celestial spheres of Ptolemaic medieval astronomy, including Mars. But Dante’s story of paradise centers the notion of transcendence, and Jon’s resignation and removal manifest as a parody of that paradise, not an attainment of it.

Jon’s detachment from humanity isn’t just because he loses the physical, carnal aspect of being human. Dante’s suffering shades have lost that aspect too, but those who haven’t ascended are as human and limited as they ever were. Dr. Osterman, though, reconstructs his consciousness as he reconstructs his body, and in doing so, becomes an exile from the human experience of linear time.

In Canto 29 of the Paradiso, Beatrice explains how the mind of God exists in an “eternity outside of time”, and that “after” and “before” did not exist until He created them. His angels, she says, have never turned their vision from the face of God, “so that their sight is never intercepted / by a new object, and they have no need / to recollect an interrupted concept.” (Translation by Allen Mandelbaum.) Dante scholar John Took sees these lines as defining a fundamental difference between human and divine experience:

Thus time enters into human experience in respect of one of the most fundamental aspects of man’s activity as man, namely in respect of his intentional reconstruction both of self and the world beyond self as the basis for everything coming next by way of its proper conception and celebration. The intentional reconstruction both of self and of the world beyond self, Dante thinks, is always temporally conditioned. It is always a matter of its successive moments. (Dante, pg. 386)

Took tends toward the obtuse and rococo, and this passage is certainly no exception, but it does help us understand just how far away Jon Osterman has been sent from us. If human experience is always temporally conditioned, always a matter of successive moments, then human experience is no longer available to Jon.

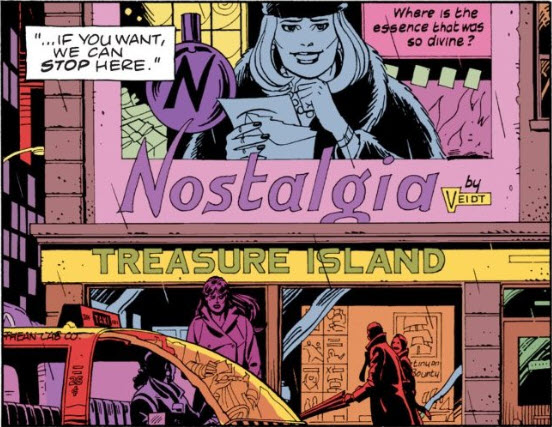

Given that reality, is it any wonder he finds himself a stranger to human morality? This panel, in a club called “Dante’s”, shows us how removed he has become from such concepts, even in 1960, well before the main events of the book’s plot. In fact, that panel is pretty much entirely devoid of morality — not just the Manhattan murder, but Moloch himself and all the sinners in the vice-den. Naming the club “Dante’s” is a perfect irony generator by Moore and Gibbons, since human morality was the basis of Dante’s entire project.

Dante explored morality by constructing an extended encounter between the human and the divine. Moore and Gibbons do something similar, but in their case the human and divine meet in a single figure, and that figure is very far from Christlike. Instead, he personifies the morality of the atomic bomb, of humankind ascended to godlike power without transcending its fundamental flaws. Jon Osterman cannot resolve this tension within himself, but he does his best to abandon it, hoping to leave our (and his) complicated and messy humanity behind for the cleaner and simpler stars.

Next entry: Soft Watchmen

Previous entry: Time Pieces

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.

In Lang’s Metropolis, the Moloch machine consumes hordes of anonymous workers. In “Howl”, Allen Ginsberg ups the ante. His Moloch destroys “the best minds of my generation.” His Moloch is a “sphinx of aluminum and cement” that “bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination.” In other words, Ginsberg’s Moloch of industrialization doesn’t just destroy the working class hands, but also the open hearts that might have tried to serve as mediators.