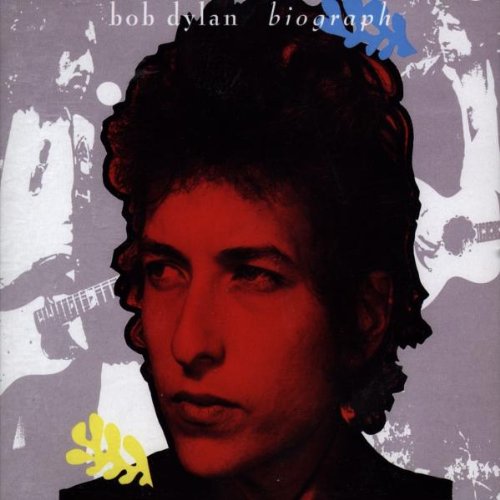

My next few assignments to Robby are taking a different tack than usual. I did a bunch of Bob Dylan research a while back, in support of a Watchmen article, and in the process wishlisted a few different Dylan things, including his 1985 box set, Biograph. Now I have it, and I’ve been listening to it, and thinking about it, and therefore I am hereby expanding the definition of “album” to include collections, including box sets. However, 53 songs is an awful lot to digest, even in two weeks, so I’m following the same approach I took with Art Of McCartney, and considering each disc a separate album for listening/writing purposes.

But I don’t think Biograph was designed with CDs in mind. It was one of the first box sets ever released for a rock artist, and in 1985 CDs were still just a small segment of the music market, albeit a rapidly growing one. So Biograph was released as both a 3-CD set and a 5-LP set, with more or less the same running order. This was back in the days when albums had sides, kids, and what I found while listening to this first disc is that those sides were pretty meaningful thematically. Even though it’s called Biograph, the set isn’t assembled chronologically. Rather than the story of Dylan’s life, it’s the story of many Dylans.

Bob Dylan The Lover

The first five songs on Biograph demonstrate a variety of approaches Dylan has taken to the love song, and unfortunately for me it starts with my all-time most hated Dylan song, “Lay Lady Lay.” I mean, I’m obviously a fan of the guy’s work, but this song is a giant exception, because it irritates the hell out of me every single time I hear it, and I end up saying out loud to the speakers, “Stop!” Stop with the smarmy lyrics. Stop referring to yourself in the third person. Stop, for God’s sake, STOP singing in that horrible Gomer Pyle voice. (Well, I guess I mean the singing voice you’d expect Gomer Pyle to have rather than Jim Nabors’ actual singing.)

Anyway, life gets better fast once we travel back to 1962 for “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down”, a cut from Dylan’s debut album. It’s a simple blues love song, sung right before the artist got a whole lot more complicated, and stopped recording covers for a long time. In fact, it’s the only tune on this collection for which Dylan lacks a songwriting credit. “If Not For You” flips the other way — like a number of Dylan’s songs, it’s more famous for its cover than the original, in this case the gorgeous version cut by George Harrison. (Not to mention the easy listening version by Olivia Newton-John. No really, not to mention it.)

“I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is a bit like a continuation of “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” — a return to simplicity from post-motorcycle-crash Dylan, and a tender declaration of protection and love, at least for tonight. But for my money, “I’ll Keep It With Mine” is the most touching song from this side. Dylan isn’t necessarily known first and foremost for his love songs, and he’s certainly left his share of relationship wreckage behind him in his personal life, but this song is such a sweet, understated offer — to share a burden, to make things a little easier… maybe just to save you a little time. It’s a loving gift, made more so by being offered so nonchalantly.

Bob Dylan The Folk Poet

One, two, three. “The Times They Are A-Changin'”, “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “Masters Of War.” Any one of these songs would have been the absolute tip-top pinnacle of somebody else’s career. In fact, most artists never put out a single song anywhere near this good. Dylan put all three of them out within nine months of each other, two of them on the same album, and laid down about a dozen other stone classics in the meantime. Seriously, is it any wonder the guy was hailed as a genius at the age of 22?

These songs are so absolutely timeless, it feels like they’ve been around forever. I mean, he actually sat down and wrote “Blowin’ In The Wind.” Even though it feels exactly like it’s been passed down through oral tradition for hundreds of years, Bob Dylan wrote it on paper, from his brain. “The Times” is still damned electrifying, 52 years on, and hundreds of listens in, for me. “Masters Of War” could have been written yesterday. In fact, in some ways it’s more timely today than ever, with destruction having become ever more corporatized and commodified, and the weapons of war so effectively marketed that now they’re available to anyone who wants to stage their own personal My Lai massacre at the local nightclub, movie theater, or elementary school.

What a gift this man had, and what a gift he gave us. To sing truth in such a universal, compelling way that it can resonate with generation after generation… it’s a special and rare thing. Even a song like “The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll”, which is literally about a story that was in the newspaper a few months before the song’s release, is still spellbinding today in the light of all-too-fresh miscarriages of justice, shining a light on the disgraceful fact that even more than 50 years later, we still find ourselves having to insist that black lives matter. “Percy’s Song” is perfectly paired with it, as it shows the flip side of judicial injustice — where in “Hattie Carroll” a casual and unrepentant murderer escapes with a 6-month sentence, Percy gets 99 years for being at the wheel in a car accident.

Bob Dylan The Rocker

With side two having impeccably established Dylan’s folk credentials, side three opens with a rocker from the same 1962 vintage. “Mixed-Up Confusion” hearkens back to Dylan’s high-school idolization of Little Richard and Elvis Presley, galloping along like it can hardly be restrained. Let a few years flow by, and that same urgent beat resurfaces in the utterly amazing “Tombstone Blues.” Man, this song is just the essence of cool. Like a lot of the tracks on Highway 61 Revisited, you can practically hear Dylan’s sunglasses on his face, as he spits out lyrics as fierce and fast as any rapper. The lyrics themselves are in that surreal Highway 61 mode, throwing archetypes and images into a blender, achieving a startling alchemy as mysterious as it is powerful.

Could Dylan still write in that mode when Biograph was current? “Groom’s Still Waiting At The Altar” says, “Hell yes!” A 1981 b-side left off Shot Of Love (and later reincluded on the CD release), this was one of the songs that rang down the curtain on Dylan’s “Born Again” period, and it’s a very strong return to form. I particularly love:

Try to be pure at heart, they arrest you for robbery,

Mistake your shyness for aloofness, your silence for snobbery,

Got the message this morning, the one that was sent to me

About the madness of becomin’ what one was never meant to be.

Like “Tombstone Blues”, it strings together thoughts and stories, returning rhythmically to a chorus that evokes desperation and wrongness. “Most Likely You Go Your Way” rocks out in a different fashion, showcasing Dylan’s remarkable facility for reworking his songs in live performance. I’ve only seen him in concert once, but the thing that most impressed me was his ability to rearrange his own songs to make them sound brand new. That’s exactly what happens here, as a rather shambolic tune from Blonde On Blonde becomes a strutting rave-up live, with Dylan shouting out the last word in every verse.

Finally, side 3 ends with “Like A Rolling Stone”, one of Dylan’s most iconic songs, and the one that proved his rock and roll prowess beyond any doubt, much to the dismay of 1965 folk purists. Books and books have been written on this song, so I’ll add nothing except to say that it’s a fitting capstone to this rock side.

Other Sides Of Bob Dylan

Towards the end of the disc, the LP structure starts to break down, as there isn’t enough space on the CD for side four. So let’s look at these last three songs just as encores for the concepts above. “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” is a fine unreleased track from Dylan in folk mode, recapturing the mood of Scottish ballads. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was the first declaration of Dylan’s rock direction, as the first song on the electric side of Bringing It All Back Home. And “I Don’t Believe You” puts it all together, as a live rock reworking of a folk original in which Bob the lover is left scratching his head at a sudden rejection.

It’s been a satisfying trip so far, but there’s so much more left. On to disc two! (Well, after my next assignment, at least.)

Leave a Reply